Earth's Rivers in 'Crisis State,' Report Concludes

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The world's rivers are in crisis, which could have a dire impact on the 5 billion people who live near them and rely on them for freshwater, as well as the thousands of species that call them home, a new study finds.

Freshwater is widely regarded as the world's most essential natural resource, underpinning human life and economic development.

Over many millennia, humans have exerted an increasing influence on freshwater resources. Rivers, in particular, have attracted humans and have been altered through dam building, irrigation and other agricultural and engineering practices. In recent times, chemical pollution, burgeoning human populations and the global redistribution of plants, fish and other animal species — invasive creatures all — have had far-reaching effects on rivers and their aquatic inhabitants.

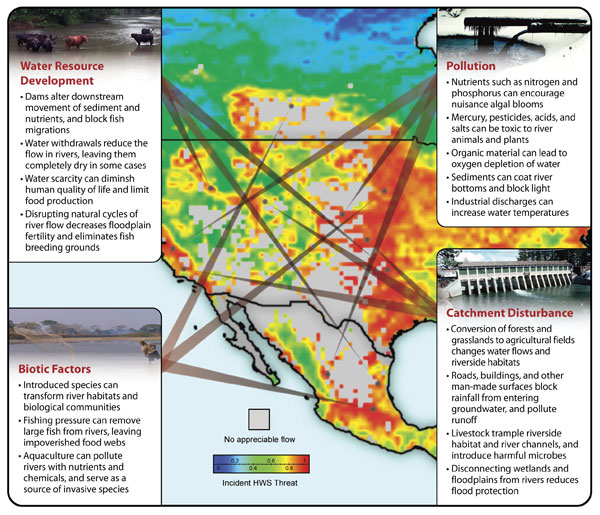

The new findings on the threats facing Earth's rivers come from the first global-scale initiative to quantify the impact of these stressors on humans and riverine biodiversity. The research team produced a series of maps documenting the influence of numerous types of threats to water quality and aquatic life across the world's river systems.

"We've integrated maps of 23 different stressors and merged them into a single index," said team member Peter McIntyre of University of Wisconsin-Madison. "In the past, policymakers and researchers have been plagued by dealing with one problem at a time. A richer and more meaningful picture emerges when all threats are considered simultaneously."

Some of the stressors to rivers that were analyzed include:

- Pollution

- Dams and reservoirs

- Water overuse

- Agricultural runoff

- Loss of wetlands

- Introduction of invasive species

"Rivers around the world really are in a crisis state," McIntyre said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers noticed that rivers in different parts of the world are subject to similar types of stresses, regardless of their presence in a developed or developing nation, such things as agricultural intensification, industrial development, river habitat modification and other factors.

"Flowing rivers represent the largest single renewable water resource for humans," said team member Charles J. Vörösmarty of the City University of New York. "What we've discovered is that when you map out these many sources of threat, you see a fully global syndrome of river degradation."

"What made our jaws drop is that some of the highest threat levels in the world are in the United States and Europe," McIntyre said. "Americans tend to think water pollution problems are pretty well under control, but we still face enormous challenges."

One of the project's goals is to support international protocols to be used for water system protection.

The findings are detailed in the Sept. 30 issue of the journal Nature.

This article is provided by OurAmazingPlanet, a sister site of LiveScience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus