How Much Water Is on Earth?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

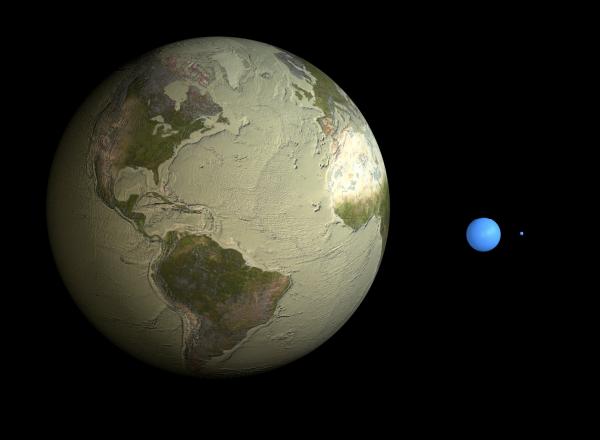

If Earth was the size of a basketball, all of its water would fit into a ping pong ball.

How much water is that? It's roughly 326 million cubic miles (1.332 billion cubic kilometers), according to a recent study from the U.S. Geological Survey. Some 72 percent of Earth is covered in water, but 97 percent of that is salty ocean water and not suitable for drinking.

"There's not a lot of water on Earth at all," said David Gallo, an oceanographer at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) in Massachusetts.

Oceans create a water layer spanning 15,000 miles (24,000 kilometers) across the planet at an average depth of more than 2 miles (3.2 km). If you poured all of the world's water on the United States and could contain it, you'd create a lake 90 miles (145 km) deep.

This seems, and looks, like a lot of water, Gallo told Life's Little Mysteries, but looks can be deceiving.

If the Earth was an apple, Gallo said, the water layer would be thinner than the fruit's skin. The Earth's freshwater is even rarer.

"For humanity to thrive, or even exist, we need to sprinkle that teeny bit of fresh water in the right places, at the right times and in just the right amounts," Gallo said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Here's how Earth's freshwater is spread around the globe:

- 70 percent of freshwater is locked in ice caps

- Less than 1 percent of the world's freshwater is readily accessible

- 6 countries (Brazil, Russia, Canada, Indonesia, China and Colombia) have 50 percent of the world's freshwater reserves

- One-third of the world's population lives in "water-stressed" countries, defined as a country's ratio of water consumption to water availability. Countries labeled as moderate to high stress consume 20 percent more water than their available supply.

There is much more freshwater stored in the ground than there is in liquid form on the surface, according to the USGS.

This article was provided by Life's Little Mysteries, a sister site to OurAmazingPlanet.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus