Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Editor's Note: This story was updated at 12:30 p.m. E.D.T. on Monday, Sept. 16

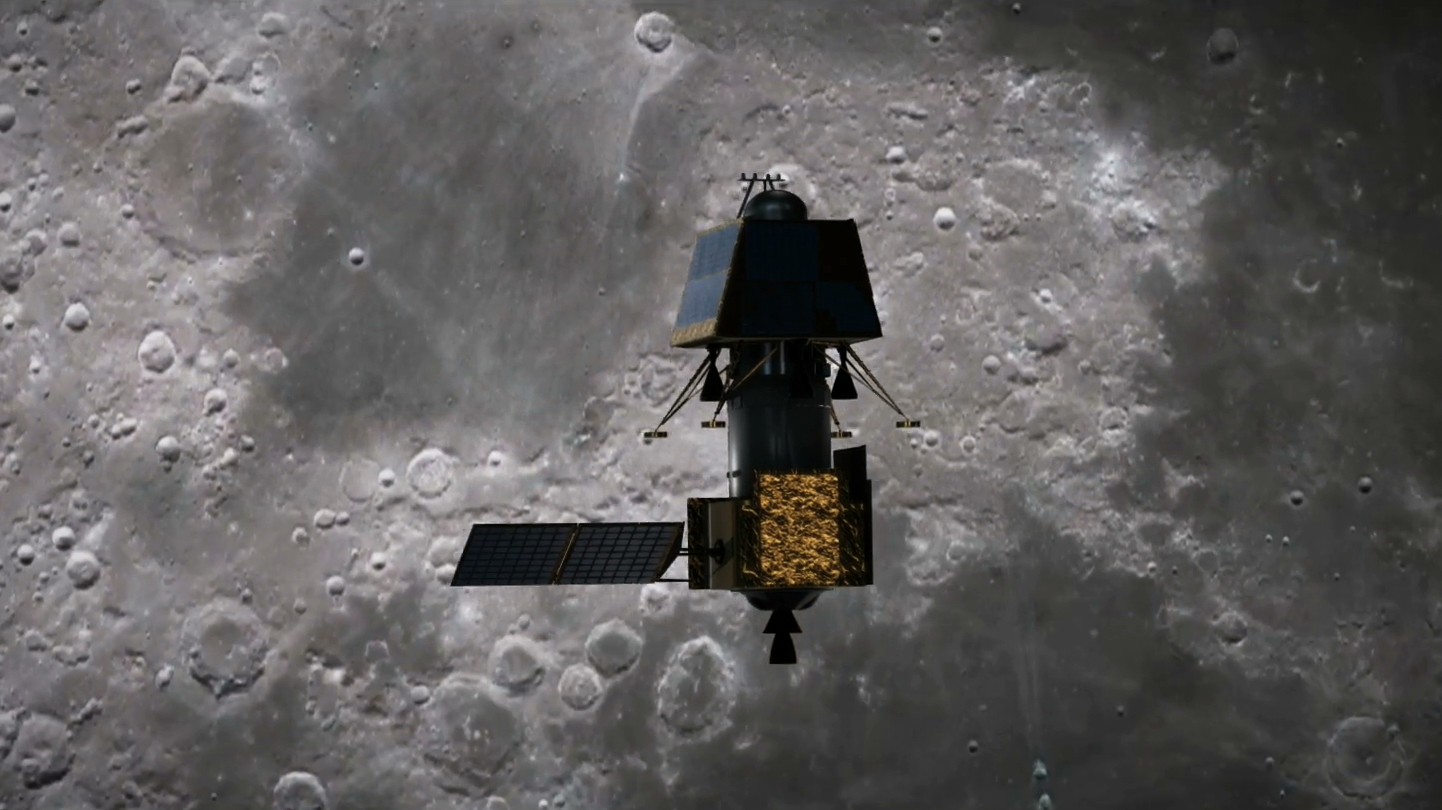

Space is hard. That was the takeaway on Sept. 7, when the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) lost contact with its Vikram lunar lander during an attempt to touch down at the moon's south pole.

India was poised to become the fourth nation to ever successfully touch down softly on the lunar regolith, doing so in a place that no other country has previously reached. Though the space agency is still scrambling to revive communication with Vikram — which has been spotted from lunar orbit — the unhappy landing sequence seemed like a painful echo of the situation earlier this year, when a private robotic Israeli lander, Beresheet, crashed into our natural satellite.

It's all a reminder that, despite the fact that humans landed on the moon many times during the Apollo missions half a century ago, doing so remains a tough business. Of the 30 soft-landing attempts made by space agencies and companies around the world, more than one-third have ended in failure, space journalist Lisa Grossman tweeted.

But why exactly is it so hard to land on the moon?

Related: 5 Strange, Cool Things We've Recently Learned About the Moon

No one particular event is responsible for the many failed attempts, aerospace engineer Alicia Dwyer Cianciolo of NASA's Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia, told Live Science. To land on the moon, "so many things have to happen in exactly the right order," she said. "If any one of them doesn't, that's when trouble starts."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

First, there's the matter of getting to lunar orbit, which is no small feat. The Apollo program's Saturn V vehicle packed in enough propellant to rocket astronauts to the moon in a mere three days. But in order to save on fuel costs, ISRO's recent Chandrayaan-2 mission, which carried Vikram, used a much more circuitous pathway and took more than a month to reach the moon.

Once in orbit, the spacecraft keep in contact with Earth using NASA's Deep Space Network, which consists of three facilities in different parts of the globe filled with ever-listening parabolic dishes that stay in touch with distant robotic probes in space. A communications failure might have been part of the reason behind Vikram's troubles, as the agency lost contact with the lander when it was just 1.2 miles (2 kilometers) above the lunar surface.

There's little room for error when a probe is screaming toward its landing spot at missile-like speeds. A faulty data transmission instrument that led to a total engine shutdown seems to be what did in the Israeli Beresheet lander on April 11, according to The Times of Israel.

On Earth, engineers can rely on GPS to help guide autonomous vehicles, but no corresponding systems exist on other celestial bodies, Dwyer Cianciolo said. "When you're traveling fast and have to slow down in a vacuum where you have very little information, it's hard no matter who you are and what you're trying to do," she added.

NASA is currently working with commercial companies that plan to deliver robots to the moon in the coming years. These future lunar navigators will need to be able to trust their sensors, Dwyer Cianciolo said.

That's why the agency is designing instruments that can sit on a vehicle’s undercarriage to scan otherworldly terrain for rocks, craters and other hazards and make course corrections, which could be used on private spacecraft as well as on future NASA missions, she added. Such technology will be tested during the descent sequence of NASA's upcoming Mars 2020 rover, which will launch next year and is scheduled to land on the Red Planet in February 2021.

Nearly all failed moon missions have been uncrewed, perhaps suggesting that it’s useful to have a person at the helm when problems arise. Back during the Apollo days, human eyes and reflexes helped make for successful landings. After spotting rocky terrain at his intended landing spot, Neil Armstrong famously took control of the Apollo 11 descent vehicle and flew in search of a safer touchdown point.

But with their backgrounds as experimental test pilots, astronauts in those days expected to have some degree of control, Dwyer Cianciolo said. "We accept autonomy a little more nowadays," she added, saying engineers would like to get to the point where future human explorers can rely on such systems to help them travel safely to and from the moon's surface.

China's Chang'e-4 probe, which landed on the lunar farside and deployed the Yutu-2 rover over the summer, provides some comfort to those worried about the difficulty of getting to the moon. Indian engineers can take solace in the fact that their Chandrayaan-2 orbiter is still functioning and doing science, and that perhaps their next attempt will be more successful.

"My heart went out to them, because you know how much work and time has gone into it," said Dwyer Cianciolo. "But we're in a business where persistence pays off, so I'm hopeful."

Editor's Note: This story was updated to correct the location of NASA's Langley Research Center. It is located in Hampton, Virginia, not Cosby, Missouri.

- Top 10 Amazing Moon Facts

- 10 Interesting Places in the Solar System We'd Like to Visit

- Apollo Moon Landing Hoax Theories That Won't Die

Originally published on Live Science.

Adam Mann is a freelance journalist with over a decade of experience, specializing in astronomy and physics stories. He has a bachelor's degree in astrophysics from UC Berkeley. His work has appeared in the New Yorker, New York Times, National Geographic, Wall Street Journal, Wired, Nature, Science, and many other places. He lives in Oakland, California, where he enjoys riding his bike.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus