What is Juneteenth?

Juneteenth is a federally-recognized American holiday observed on June 19. It is also known as Emancipation Day and Black Independence Day. In 2023, it falls on a Monday.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Juneteenth is a federally-recognized holiday in the U.S. that celebrated on June 19. It commemorates the day in 1865 when the Emancipation Proclamation — the federal order ending slavery in the United States — was read to enslaved African Americans in Texas. In 2023, Juneteenth falls on a Monday.

On June 19, 1865, Union troops led by Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger arrived in Texas, where he announced the end of the Civil War and the abolition of slavery nationwide. The war had ended just two months earlier, when Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee surrendered on April 9, 1865; and it had been two years and nearly six months since the proclamation ending slavery was signed by President Abraham Lincoln, on Jan. 1, 1863.

However, Confederate states that were still in open rebellion against the federal government in 1863 didn't recognize President Lincoln's authority, and many slaveholders didn't comply with the order until Union troops arrived to enforce it, according to the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC).

Article continues belowAfter learning they were free, formerly enslaved African Americans in Texas adopted June 19, nicknamed Juneteenth, as a day to celebrate freedom. In the following decades, the holiday — also known as Emancipation Day and Black Independence Day — was embraced by African American people across the country, the NMAAHC says.

In June 15, 2021, the U.S. Senate unanimously passed a bill making Juneteenth a federally recognized holiday, with the House of Representatives following suit on June 16. The bill was signed into law by President Joe Biden on June 17, 2021. According to NPR, "The recognition of Juneteenth as a legal holiday comes amid a broader national reckoning on race and the racism that helped shape America."

Related: 4 myths about the history of American slavery

Meaning of Juneteenth

On June 19, 1865, Maj. Gen. Granger read from Lincoln's General Order Number Three to people in Galveston, Texas, one of the busiest port cities in the U.S. at the time. The document declared that "the people of Texas are informed that in accordance with a Proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them became that between employer and free laborer," according to the Obama White House Archives.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Many Texan slaveholders and enslaved people likely already knew about Lincoln's order when it became a law two years earlier, but without Union troops to enforce it, slave ownership in Texas "was business as usual" into 1865, said Michael Hurd, director of the Texas Institute for the Preservation of History and Culture at Prairie View A&M University in Prairie View, Texas.

During that two-year window, "Texas was considered a safe haven to practice slavery," and slaves who were brought to Texas from other states helped to spread the word among enslaved African Americans about emancipation elsewhere in the failing Confederacy, Hurd told Live Science.

"I think a lot of people, Black and white, knew about the emancipation," Hurd said. "But the people in power — slave owners — made no effort to free their slaves until they absolutely had to, when the Union troops came through."

History of Juneteenth

The first Juneteenth celebrations took place in 1866 throughout East Texas — from Texarkana in the northeast down to Houston — because that's where the majority of the state's African Americans settled after emancipation, Hurd said. Churches often hosted Juneteenth celebrations, and as African Americans became landowners, they donated and dedicated land for Juneteenth festivities, according to Juneteenth.com, a web portal for Juneteenth information and history.

Some formerly enslaved people who left Texas for Mexico after the Civil War brought the holiday with them, where it is still observed today, said Kelly Navies, a Museum Specialist in Oral History for the NMAAHC.

"You will find it celebrated on June 19th in some parts of northern Mexico, as el Día de los Negros," Navies told Live Science.

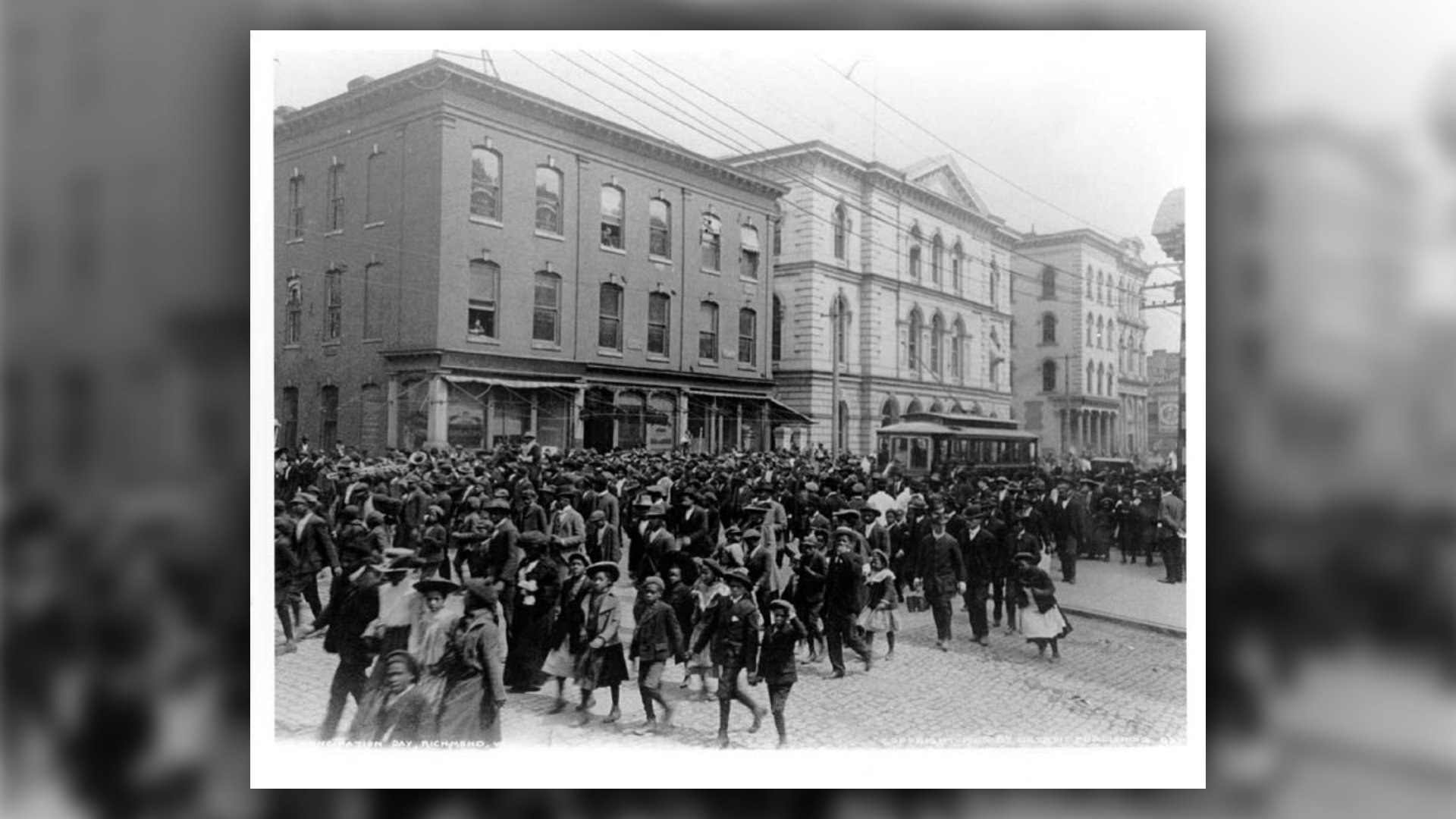

African Americans observed Juneteenth with feasting, music, pageants and parades, with many dressing in fine clothes — a luxury denied when they were enslaved. But the holiday was also an opportunity to hold political rallies so that newly freed African Americans could learn about voting rights, according to the Texas State Historical Association.

A newspaper article from Austin, Texas, in 1869 described that year's Juneteenth celebration, mentioning a procession led by a parade marshal through local barbecue grounds, said Daina Ramey Berry, a Radkey Professor of History at the University of Texas at Austin.

"They had drummers; a flag bearer; they were holding the Stars and Stripes. Many of the men on horses were decorated with bright-colored ribbons," Berry told Live Science.

Many of the first Juneteenth celebrations were also oral history events during which speakers would talk about life under slavery, Berry explained.

"In the early festivals in the 1860s and 1870s, when you had formerly enslaved people still alive, those elders would speak at these ceremonies and educate the young generations," she said. "It's like a public oral history lesson, where the community is learning about a difficult part of our history, but it is a part of our history that needs to be acknowledged."

And unlike the Fourth of July, America's national celebration of independence from British rule, Juneteenth commemorates freedom for all in America, Berry said. Frederick Douglass, the renowned African American writer and orator, delivered a keynote address at an Independence Day celebration in 1852, now known as "What to the Slave, Is the Fourth of July?" (it was formerly titled "The Meaning of July Fourth for the Negro"). In it, Douglass called out the hypocrisy of declaring a holiday devoted to freedom, in a land where approximately 4 million African Americans were not free.

From the perspective of enslaved people, "your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your sounds of rejoicing are empty and heartless," Douglass wrote. For African Americans who embraced Juneteenth, the holiday "represents the Independence Day that they want to honor and celebrate," said Berry.

Spread of Juneteenth

During the 1920s and the decades that followed, millions of African Americans left the South and moved to cities in northern and western states, in what is known as the Great Migration — and the celebration of Juneteenth traveled with them. "Because of that, you started to see those celebrations grow in communities around the country," Hurd said.

Interest in Juneteenth surged again in the 1950s and 1960s, spurred by the activism of the Civil Rights movement.

In 1979, the state of Texas passed a bill declaring June 19, "Emancipation Day in Texas," making it a legal state holiday starting in 1980, according to the Texas State Library and Archives Commission.

On June 15, 2021, the U.S. Senate passed another resolution meant to make Juneteenth a federal holiday. The House of Representatives followed suit on June 16, 2021, and on June 17 President Biden signed the legislation that officially declared Juneteenth a federal holiday, reported the New York Times.

Gaining federal recognition for Juneteenth "would mean that we're starting to come to terms with some of the important lessons of that time period of slavery and reconstruction that we've had a hard time as a nation confronting," Navies said in an earlier interview.

"Juneteenth forces you to look at what the meaning of enslavement was, and what the meaning of being free means to African Americans today, and to 4 million African Americans at that time," she said. "It's a day where you're not just celebrating — you're reflecting on what's happened since the year 1865."

However, some saw the move to make Juneteenth a federally recognized holiday as a hollow action. Nneka D. Dennie, assistant professor of history at Washington and Lee University, was one such critic. In an article for Slate, she pointed out that other holidays, like Martin Luther King Jr. Day, were once rooted in Black history but have become disconnected from that past.

"Given the ways that Dr. King’s lifework and MLK Day have been distorted," Dennie wrote, "it seems valid to fear that making Juneteenth a federal holiday has the potential to diminish its significance, instead of generating further inquiry into the history of American slavery and emancipation."

Additional resources

- Listen to an interview with Clint Smith about why Juneteenth is important for kids to learn about in schools on WBUR.

- Read President Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation here.

- Watch a brief documentary about the history of Juneteenth, from the Minnesota Historical Society.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus