Here's how to watch the longest partial lunar eclipse of the century live or online

The nearly total lunar eclipse will last nearly 3.5 hours.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Earth's dark shadow will cover nearly all of the moon early Friday morning (Nov. 19), tinting the moon a rusty red in what will be the longest partial lunar eclipse of the century. So, what's the best way to watch this nearly 3.5-hour long celestial show?

If you live in a prime viewing spot, which includes all 50 U.S. states, set your alarm clock for 2:19 a.m. EST (7:19 GMT) if you want to see the beginning of the partial eclipse, and for just after 4 a.m. EST (9:00 GMT) to see Earth's shadow cover 97% of the moon, turning it an eerie red.

But if you have bad weather, don't live in a good viewing location or simply don't want to wake up super early on Friday, Live Science has your back: we'll provide links below to live streams showing all 3 hours, 28 minutes and 23 seconds of the partial lunar eclipse from different cities around the world.

Related: Photos: Super Blood Wolf Moon eclipse stuns viewers

The partial eclipse coincides with November's full moon, also known as the Micro Beaver Moon. This moniker refers to the historic beaver trapping season among some Indigenous people in North America, as well as the moon's "micro" appearance, as the moon will be at apogee, or the farthest away in its elliptical orbit from Earth. This far-flung distance is why micromoons look about 14% smaller and 30% dimmer than supermoons, which occur at perigee, or when a full moon is closest in its orbit to Earth, Live Science previously reported.

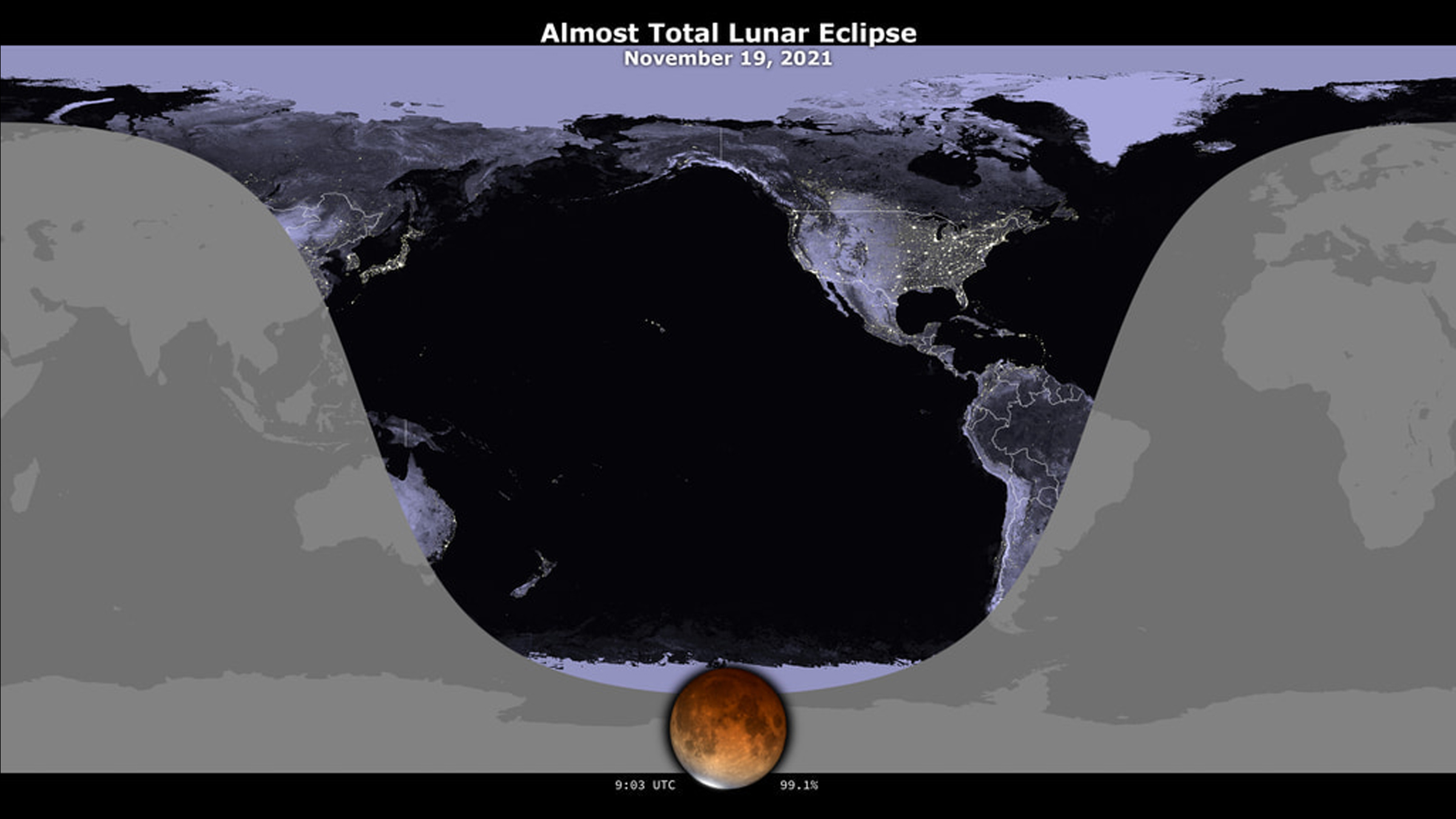

The peak part of Friday's partial lunar eclipse, when Earth's shadow will cover the vast majority of the Beaver Micro Moon, will be visible from North America and large parts of South America, Polynesia, eastern Australia and northeastern Asia, according to NASA.

Here's a timetable to help skywatchers time their eclipse-viewing escapades on Friday. As the moon crosses into Earth's dark shadow, called the umbra, it will look as if a bite was taken out of the moon. When upward of 95% of the moon is in the umbra, the moon will turn a dull burgundy. That's because even though Earth is blocking sunlight from reaching the moon, the sun's rays still travel around our planet. This light goes through Earth's atmosphere, which filters out shorter wavelengths, like blue, but allows the longer wavelengths of red and orange through, Live Science previously reported. These reddish wavelengths temporarily turn the moon brick red.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

| EST | PST | GMT | Event | What's happening |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2:19 a.m. | 11:19 p.m. (Nov. 18) | 7:19 a.m. | Partial eclipse begins | Moon enters Earth's umbra. It will look as if the moon has a bite taken out of it. |

| 3:45 a.m. | 12:45 a.m. (Nov. 19) | 8:45 a.m. | Moon turns red | Upward of 95% of the moon is in the umbra, making it appear red. |

| 4:03 a.m. | 1:03 a.m. | 9:03 a.m. | Eclipse peak | This is the best time to see the red moon. |

| 4:20 a.m. | 1:20 a.m. | 9:20 a.m. | Goodbye red moon | The red color fades as less than 95% of the moon is in the Earth's umbra. It will look as if a bite was taken out of the opposite side of the moon from before. |

| 5:47 a.m. | 2:47 a.m. | 10:47 a.m. | Partial eclipse ends | The moon exits the umbra. |

If you're unable to catch the eclipse in person, here are some websites providing live streams. You can catch the show live at Live Science starting at 2 a.m. EST.

Also, starting at 2 a.m. EST (7:00 GMT) on Friday, join the Virtual Telescope Project, a Rome-based project that is coordinating with astrophotographers in Australia, the U.S., Panama and Canada to provide footage of the partial lunar eclipse.

You can also join timeanddate.com for live coverage starting at 2 a.m. EST (7:00 GMT) on Friday. "If the skies are clear, residents of the Pacific Ocean, North and South America, Australia, and parts of Europe and Asia will see November's Full Moon turn a shade darker," timeanddate.com wrote on YouTube.

Live Science would like to publish your partial lunar eclipse photos. Please email us images at community@livescience.com. Please include your name, location and a few details about your viewing experience that we can share in the caption.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus