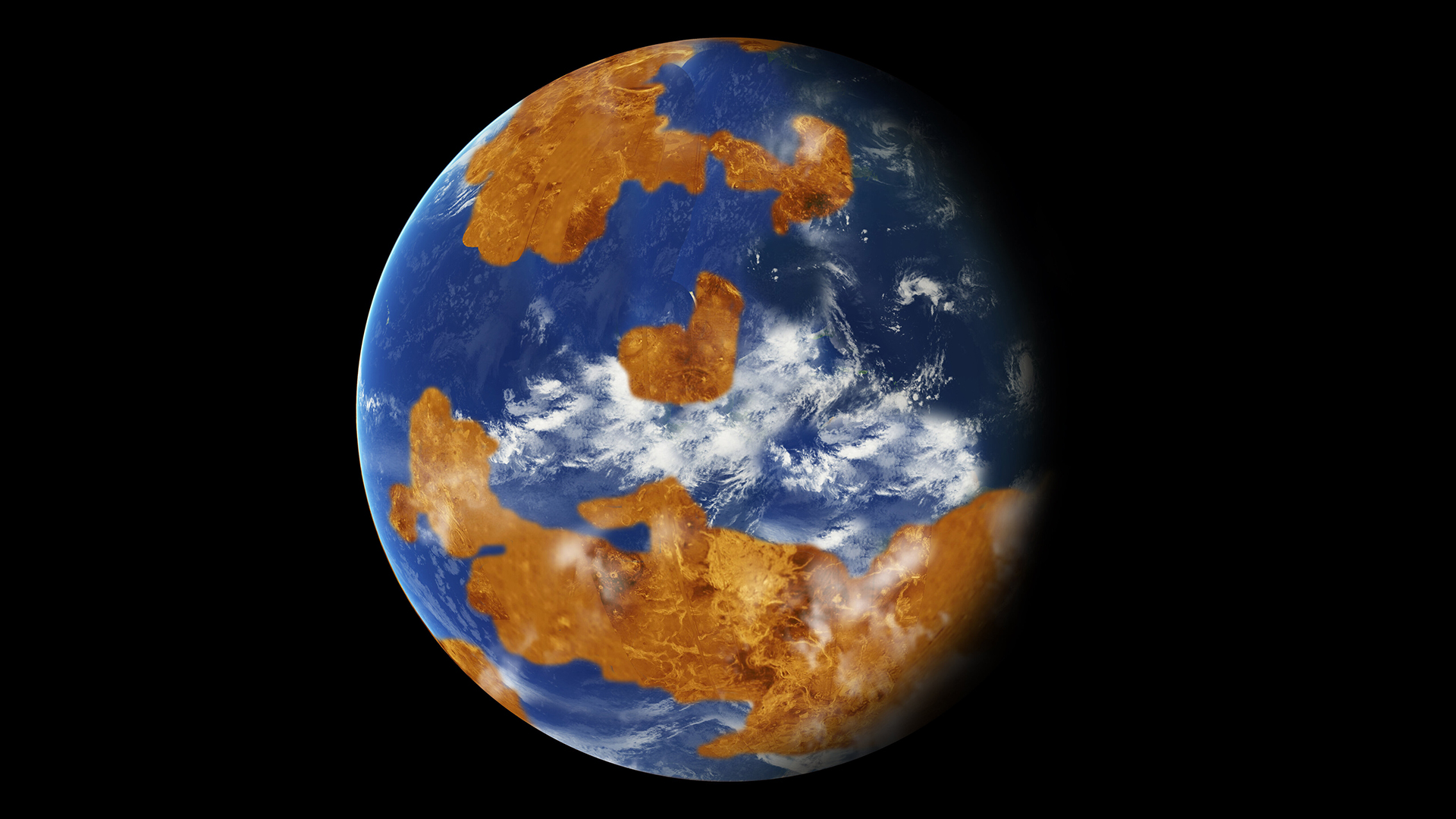

Did Venus, Earth's 'Twisted Sister' Hellscape Planet, Once Harbor Water — and Life?

Vast seas may have covered "hellish hothouse" Venus for billions of years.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Venus, our solar system's broiling, radiation-bombarded, sulfuric-acid-raining, toxic hellscape of a planet, may once have hosted vast oceans ... and could have been rather nice, actually.

In fact, a water-covered and life-friendly Venus possibly persisted for as long as 3 billion years, scientists recently reported.

But that idyllic time in Venus' past ended abruptly between 700 million and 750 million years ago, when a near-planet-wide release of carbon dioxide (CO2) stored in surface rocks disrupted the planet's atmosphere and triggered its transformation to the "hellish hothouse" that we know today, researchers said in a statement.

Related: 9 Most Intriguing Earth-Like Planets

Venus and Earth could be planetary twins — well, almost. They're similar in size and mass, but that's where the resemblance ends. Venus' surface temperatures are a face-frying 864 degrees Fahrenheit (462 degrees Celsius), hot enough to melt lead, according to NASA. Venus' surface holds lava plains, craters, volcanoes and mountains, but they're hidden under dense clouds of sulfuric acid. The planet's atmosphere is mostly CO2 and nitrogen, and is about 90 times as thick as Earth's atmosphere, NASA said.

This ferociously inhospitable environment makes Venus incapable of sustaining most life as we know it; Venus is therefore sometimes referred to as Earth's "twisted sister."

Or does it? Once upon a time, this now-hotter sibling may have had more in common with Earth, such as abundant water, a stable climate and suitable conditions for hosting life, scientists said. The researchers presented their findings on Sept. 20, at The 2019 Joint Meeting of the European Planetary Science Congress (EPSC) of the Europlanet Society, and the Division for Planetary Sciences (DPS) of the American Astronomical Society (AAS), in Geneva.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Using computer simulations, the scientists expanded on their prior findings about Venus's potential habitability, which they published in 2016 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters. In that study, they described a young, slow-spinning Venus with habitable surface temperatures and a shallow ocean of liquid water.

This time, they tested their hypothesis with more variables in their models. They created five scenarios that used different topographies for the planet's surface; varying amounts of ocean coverage; and different chemical compositions in the atmosphere, said co-presenter Michael Way, a researcher with NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies.

"We also modeled different epochs in time, which we did not do previously," Way added. The models looked at Venus during three periods: around 4.2 billion years ago, which was shortly after its formation; around 715 million years ago; and as the so-called hell planet appears today.

Venus is currently bombarded with about twice as much solar radiation as Earth, and some experts have suggested that it lies too close to the sun to have ever hosted oceans at all. Nevertheless, the new models showed that billions of years ago, that radiation wouldn't have prevented Venus from having water on its surface, the scientists said.

In the simulations, the infant Venus cooled rapidly after forming, developing an atmosphere dominated by CO2; other scientists' climate models of a young Earth have also used a CO2-rich atmosphere, Way told Live Science. But by 715 million years ago, nitrogen became the most abundant atmospheric element.

In all of their simulations, Venus maintained stable surface temperatures for about 3 billion years of between 68 F (20 C) and 122 F (50 C). Under those conditions, liquid water — and possibly life — could have been feasible, the scientists said.

"If Venus had a surface with liquid water in its ancient past, our models show that it could have had habitable conditions," Way said.

- Too Hot to Handle: 7 Sizzling Places on Planet Earth

- 25 Strangest Sights on Google Earth

- Changing Earth: 7 Ideas to Geoengineer Our Planet

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus