Nazi bomb plot cubes could finally be identified

A new technique could be vital to tracing the illegal trafficking of nuclear material.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

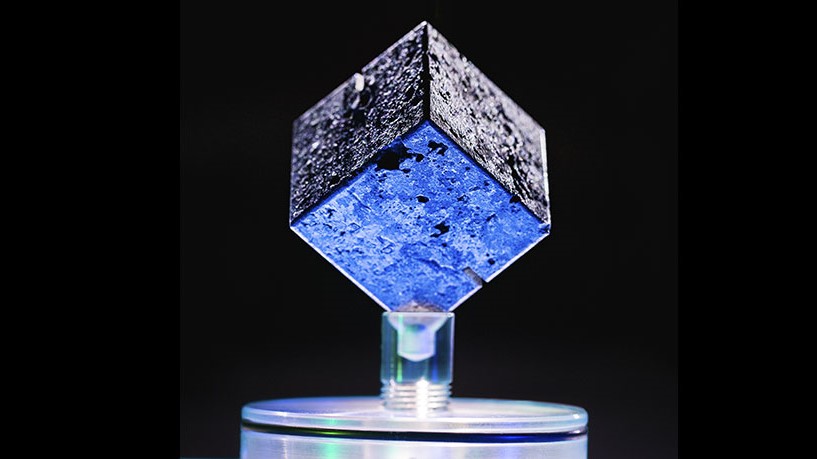

Scientists have developed a new method to identify and trace the origins of hundreds of uranium cubes that went missing from the Nazi atomic weapons program.

More than 600 "Heisenberg cubes" — vital components of the Nazis' plans to build both a nuclear reactor and an atomic bomb and named after Werner Heisenberg, one of the German physicists who created them — were seized from a secret underground laboratory at the end of World War II and brought to the United States. Over 1,200 uranium cubes were believed to be created across Nazi Germany. But today, researchers only know the locations of roughly a dozen.

The new technique, tested on a cube that mysteriously found its way to the researchers at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) in Washington state, was presented Tuesday (Aug. 24) at a meeting of the American Chemical Society and could help track down illegally trafficked nuclear material.

Related: The 22 weirdest military weapons

Alongside their own cube, the researchers have access to a few others held by research collaborators. They hope their new technique will be able to not only confirm the cubes' provenance in Nazi Germany, but also tie them to the specific labs where they were first created.

"We don't know for a fact that the cubes are from the German program, so first we want to establish that," Jon Schwantes, a senior scientist at the PNNL, said in a statement. "Then, we want to compare the different cubes to see if we can classify them according to the particular research group that created them."

When Adolf Hitler first came to power, German nuclear experiments were at the cutting edge of research. In 1938, German radiochemists Otto Hahn and Fritz Strasserman were the first to split the atom to release enormous amounts of energy. During World War II, German scientists competed to find a way to transform cubes of uranium into plutonium — a key ingredient in early nuclear bombs — using prototype reactors.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

German scientists hung the cubes, just 2 inches (5 centimeters) wide on each side, on cables and submerged them in "heavy" water, in which hydrogen is replaced by a heavier isotope called deuterium. The German scientists hoped their reactors would trigger a self-sustaining chain reaction, but their designs failed.

Two prominent physicists led these experiments: Kurt Diebner, who ran experiments at Gottow, and Werner Heisenberg, who conducted them first in Berlin and later in a secret lab below a medieval church in Haigerloch to better hide from Allied troops. Heisenberg, a Nobel Prize-winning physicist who was once called a "white Jew" by a rival physicist, Johannes Stark, for his open admiration of Albert Einstein's work on relativity and quantum mechanics, nonetheless worked to build an atomic bomb for Nazi Germany.

After discovering Heisenberg's lab in 1945, U.S. and British forces retrieved 664 of the cubes that were buried in a nearby field and shipped them to the U.S. Some may have been used in the American nuclear weapons effort, while others found their way into the hands of collectors.

The chaotic collapse of the Nazi nuclear program likely means that many of the cubes could still be out there. Hundreds of the cubes from Diebner's laboratory disappeared. Reports abound of physicists who acquired cubes handing them out as souvenirs, and the Smithsonian Institution in Washington D.C. even has a cube that was discovered in a drawer in New Jersey. Another cube, retrieved from a German creek, was said to have been tossed in by Heisenberg himself during his desperate flight from advancing Allied forces.

The PNNL researchers suspect they have a Heisenberg cube, but they aren't sure. To test the cube's origins, the team is relying on radiochronometry, a technique geologists use to date samples of ancient rocks and minerals based on the presence of naturally occurring radioactive isotopes. The technique could reveal the age of the cube and, potentially, where the original uranium was mined. This technique might not just be useful in finding the origins of the Heisenberg cubes, but in tracing the provenance of other smuggled nuclear materials.

Because different Nazi laboratories applied different chemical outer coatings to their cubes to limit oxidation, a second technique the team is developing could also trace the cubes to the scientists who created them. The researchers have already discovered that their cube, believed to be from Heisenberg's lab, actually has the styrene-based coating from Diebner's lab. This finding means the cube could be one of those that Diebner reportedly sent to Heisenberg, who was trying to gather more fuel for his new reactor, Schwantes said.

Despite being essential applications in developing tracing techniques for nuclear material today, the cubes are an unsettling reminder of how close we came to an altogether different history.

"I'm glad the Nazi program wasn't as advanced as they wanted it to be by the end of the war," said Brittany Robertson, a doctoral student at PNNL. "Because otherwise, the world would be a very different place."

Originally published on Live Science.

Ben Turner is a U.K. based writer and editor at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus