Toddler swallowed half a dozen tiny magnets. Some got stuck in his throat.

A pair of the powerful magnets became stuck in his throat, adhering to each other and pinching his tissue.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

After a toddler swallowed six tiny-but-powerful magnets, two of them became stuck in his throat, adhering to each other and pinching his tissue, according to a new report of the case.

The 3-year-old swallowed the magnetic beads, which were part of a toy, while his older sister was babysitting him, according to the report, published Jan. 19 in The Journal of Emergency Medicine. When his parents found out, they took him to the emergency room.

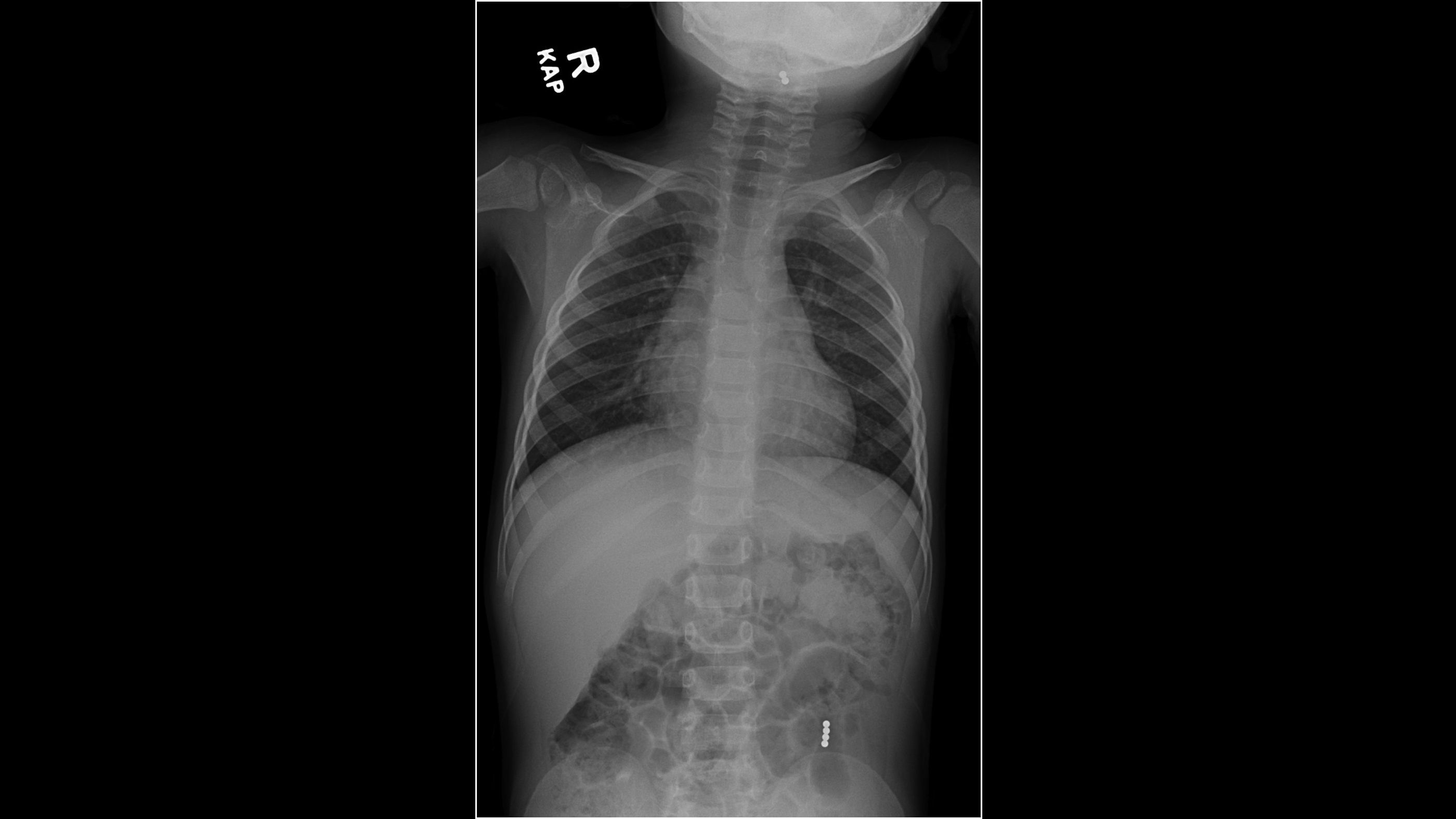

An X-ray showed that the boy had two magnetic beads in his throat and four in his abdomen. The boy didn't have trouble breathing, but he said he felt a mild pain when swallowing.

Related: 11 weird things people have swallowed

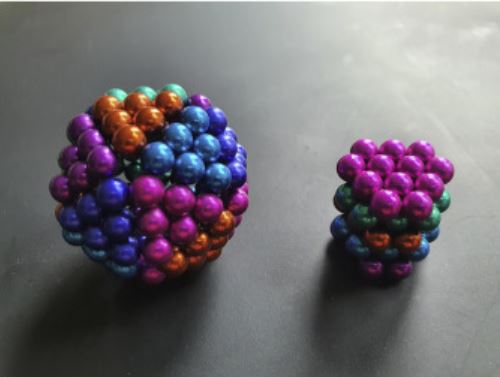

These bead toys, which typically contain powerful magnets made from rare-earth elements, pose significant risks to young children, who may accidentally swallow them. Inside the body, magnets can stick together and wreak havoc. For example, the magnets can attract each other through loops of the gastrointestinal tract and potentially tear a hole in the bowel wall, Live Science previously reported. Usually, however, doctors report on magnets stuck inside the gastrointestinal tract rather than the throat; this case of throat obstruction appears to be only the fourth one in the medical literature.

In the boy's case, doctors used a small, flexible telescope (or "scope") to view the back of the throat, including the larynx (voice box). They saw two colored beads that were magnetized to each other, but on opposite sides of a fold of mucous membrane.

"They were right in the back of the throat just above the vocal cords, on the edge of the airway/trachea," Dr. Emily Powers, lead author of the report and a clinical fellow in Pediatric Emergency Medicine at Yale University School of Medicine, told Live Science in an email. "This was very worrying, because [if] they came apart, one could fall into the trachea to the lungs," where they could cause chocking or pneumonia, Powers said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The boy was rushed to the operating room, where doctors inserted metal forceps so they could grasp the magnets. But then, the magnets became attracted to the forceps and stuck to the instrument, the report said. Still, doctors were able to successfully remove the magnets, and the boy experienced no injuries.

Because the boy still had four magnetic beads in his gastrointestinal tract, he stayed in the hospital overnight for observation. He didn't have any abdominal pain and was able to eat normally, so he was allowed to go home the next day. Three days later, the boy passed the four magnets in his stool, according to his parents.

The new report "adds to the body of evidence highlighting the negative effects of these magnetic foreign bodies in young children," the authors wrote in their paper.

The magnetic beads and similar toys pose such a hazard to children that in 2014, the Consumer Product Safety Commission banned the toys from the U.S. But a U.S. court ruling in 2016 lifted the ban, and since then, there has been a 400% increase in the number of magnet ingestions by children and related hospitalizations, according to Nationwide Children's Hospital.

When treating children who have swallowed magnets, doctors need to act quickly, the authors wrote in the study. "Early recognition and removal of magnetized rare-earth magnets are essential in preventing pressure necrosis [tissue death] and maximizing patient outcomes," the authors noted. Doctors should perform imaging from the neck to the pelvis to make sure they don't miss any magnets, they added.

Parents who think their child has swallowed magnets should contact their local poison control center and be aware that they may need to go to the emergency room, according to Nationwide Children's.

Editor's note: This article was updated on Jan. 25 to include quotes from study lead author Dr. Powers.

Originally published on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus