Americans celebrated Thanksgiving during a pandemic before. Here's what happened.

The war was over, families were reuniting, and a deadly influenza surge was just around the corner.

For the second time in a little over a century, the world is about to face the winter holidays amidst a raging pandemic.

This year, as new COVID-19 cases soar to record high numbers in the U.S., bedrock holiday traditions like interstate travel and indoor family gatherings have been called into question. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has advised American families not to dine with anyone outside their households this Thanksgiving, while some cities are following Europe's lead in imposing new lockdown restrictions.

But in late November 1918 -– after a strain of influenza called the Spanish flu had killed nearly 300,000 Americans in just a few months –- the holiday outlook was very different. New cases were plummeting. World War I was over. Troops were returning to their families –- and Americans were ready to party.

"There was definitely a mixed message after Armistice Day [Nov. 11, 1918]," Nancy Tomes, a history professor who studies public health at Stony Brook University in New York, told Live Science. "There was a leftover concern about big public gatherings, and some cities issued stern warnings before the holidays. But there was also this tremendous conflation of gratitude that the war was finally over. The dominant tone to the public was: Be grateful, celebrate that we've come through this national emergency, go to church, say your prayers."

Related: 20 of the worst epidemics and pandemics in history

But even as Americans celebrated and took care of one another's physical and psychological needs, a new wave of infections was lurking just around the corner. For some communities, it would prove devastating.

Burning like wildfire

The influenza pandemic of 1918 was one of the deadliest the world had ever seen, ultimately infecting roughly one-third of the global population, and killing more than 50 million people.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

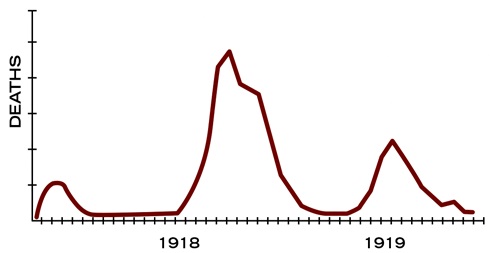

Unlike the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, the Spanish flu hit America in four discrete spikes, with new infections dropping significantly between them. The first wave hit in March 1918 and was relatively mild; CDC records show that the U.S. reported roughly 75,000 flu-related deaths in the first six months of 1918, compared with 63,000 during the same period in 1915. (Modern medicine has helped halve those numbers; in the 2018-2019 flu season, America reported 34,000 flu-related deaths).

The second wave, which began in September, proved far deadlier.

"The 'great influenza' tears through the U.S. beginning in late September, and by mid-November it's done in most of the United States," Tomes said. "It moves fast, and it burns out."

Related: 28 devastating infectious diseases

Between September and December 1918, more than 290,000 Americans died of flu-related illness, compared with just 26,000 during the same period in 1915, the CDC reported. Fatalities peaked in October, with an estimated 195,000 Americans killed in that month alone. (In Canada, which traditionally celebrates Thanksgiving in October, the holiday was officially postponed until December.)

The entire U.S. was already rationing food and restricting spending to help the war effort, but many cities met the virus with further restrictions that would seem familiar today — such as lockdowns, mask mandates and social-distancing requirements — and a few that wouldn't seem so familiar, like New York City's crackdown on public spitting at the time. Cities with lax restrictions were hit hardest; infamously, a Sept. 28 parade to promote war bonds in Philadelphia became a super-spreader event that resulted in more than 12,000 flu deaths within a month, according to the University of Pennsylvania.

As cases plummeted in early November, the nation's attention turned to victory, Tomes said. As Crosscut reported, papers like The Seattle Times wrongly declared victory over influenza and victory in Europe simultaneously, as city officials promptly ended lockdowns and social-distancing restrictions. Charity organizations hosted dinners for thousands of troops separated from their families, and citizens around the country gathered for "victory sings" and other spontaneous parties to celebrate the war's end. In his official Thanksgiving proclamation in mid-November, President Woodrow Wilson urged Americans to "be grateful and rejoice" at home and in houses of worship.

"Everybody is out celebrating during this great patriotic burst, and you don't see public health officials saying 'stay home,'" Tomes said. "Psychologically, people believed the pandemic was done. I think you see a lot of people going through that now."

The third wave

In hindsight, it seems obvious that the third wave of the Spanish flu pandemic would follow a season of intimate gatherings and public celebration. Tens of thousands of new cases were reported between December 1918 and April 1919, many of which arose in metropolitan hotspots.

In the first five days of January 2019, San Francisco reported 1,800 flu cases and more than 100 deaths, according to the CDC, and other big cities like New York, Minneapolis and Seattle were similarly hard-hit. Overall, however, the spike that followed the 1918 winter holidays was not nearly as deadly as the autumn spike that preceded them. The fourth wave, which began in winter 1919, similarly saw widespread infections around the U.S., though not nearly as many as autumn 1918 did.

It's hard to draw specific parallels from that pandemic to COVID-19, Tomes said, because everything about it — from the nature of the virus itself, to the world war that facilitated its spread — was totally different than today. Even the culture of the time, which was beset constantly by the threat of deadly diseases like tuberculosis and scarlet fever, may have made Americans more willing to "accept that microbes were powerful agents of nature," Tomes said. This daily risk may have made Americans more psychologically prepared for the death toll of a pandemic 100 years ago than we are today, she added.

One thing that is clear, though, is that influenza cases surged after the holiday seasons of 1918 and 1919, just as coronavirus infections are predicted to surge again in late 2020 and early 2021. Despite the overwhelming air of celebration after the war, some cities did ultimately cancel their Thanksgiving plans as small outbreaks popped up. When public gatherings were banned in Richmond, Indiana, shortly before Thanksgiving 1918, a reporter at the local newspaper characterized the imminent holiday as "a pleasant Thanksgiving with nothing to do." Hopefully, that's the worst that can be said about Thanksgiving 2020, as well.

Originally published on Live Science.

Brandon is the space / physics editor at Live Science. With more than 20 years of editorial experience, his writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. His interests include black holes, asteroids and comets, and the search for extraterrestrial life.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus