The World's Thickest Mountain Glacier Is Finally Melting, and Climate Change Is 100% to Blame

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

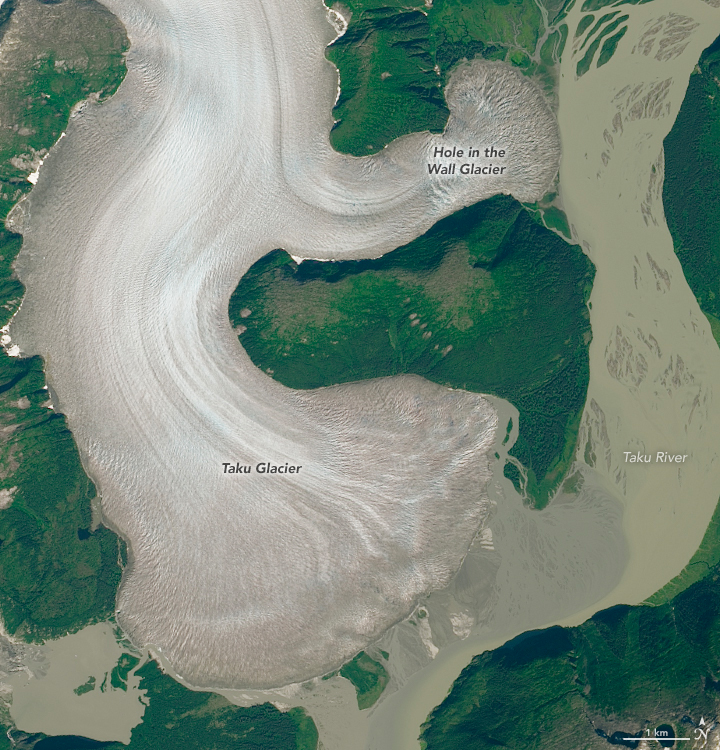

Massive and meaty, the Taku Glacier in Alaska's Juneau Icefield was a poster child for the frozen places holding their own against climate change. As the largest of 20 major glaciers in the region and one of the single thickest glaciers in the world (it measures 4,860 feet, or 1,480 meters, from surface to floor), Taku had been demonstrably gaining mass and spreading farther into the nearby Taku river for nearly half a century, while all of its neighboring glaciers shrank. Now, it appears those glory days are over.

In a new pair of satellite photos shared by NASA's Earth Observatory, the slow decline of Taku Glacier has finally become apparent. Taken in August 2014 and August 2018, the photos show the icy platforms where the glacier meets the river retreating for the first time since scientists began studying Taku, in 1946.

While the shrinkage is subtle for now, the results are nonetheless shocking. According to glaciologist Mauri Pelto, who has studied the Juneau Icefield for three decades, Taku was predicted to continue advancing for the rest of the century. Not only have these signs of retreat arrived about 80 years ahead of schedule, Pelto said, but they also snuff a symbolic flicker of hope in the race to understand climate change. Of 250 mountain (or "alpine") glaciers that Pelto has studied around the world, Taku was the only one that hadn't clearly started to retreat.

Related: Photographic Proof of Climate Change: Time-Lapse Images of Retreating Glaciers

"This is a big deal for me because I had this one glacier I could hold on to," Pelto, a professor at Nichols College in Massachusetts, told NASA. "But not anymore. This makes the score climate change: 250 and alpine glaciers: 0."

Pelto discovered Taku Glacier's retreat as part of a new study published Oct. 14 in the journal Remote Sensing. Using satellite data, Pelto looked at a region of the glacier known as the transient snow line, or the place where snow disappears and bare glacial ice begins. If a glacier loses more mass to melting than it gains from snow accumulation during a particular year, its snow line moves to higher altitudes. The relative position of this line can help researchers calculate changes in the glacier's mass from year to year.

Historical records show that between 1946 to 1988, Taku Glacier had been gaining mass and advancing (that is, growing) by about a foot per year. After that, the advancement began to slow and the ice started to thin a bit. From 2013 to 2018, advancement stopped altogether — then, in 2018, the glacier finally started to retreat. In that year, Pelto observed the greatest mass loss and the highest snow line in Taku glacier's history. Those changes coincided with the warmest July on record in Juneau, Pelto wrote.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

While it was inevitable for even a glacier as thick as Taku to transition eventually from a period of advancement to one of retreat, those transitions generally result after decades of stability where the glacier's edge does not move at all. Taku's transition from growth to decay, meanwhile, seems to have lasted only a few years.

"To be able to have the transition take place so fast indicates that climate is overriding the natural cycle of advance and retreat that the glacier would normally be going through," Pelto said.

- Images of Melt: Earth's Vanishing Ice

- The Reality of Climate Change: 10 Myths Busted

- Top 10 Ways to Destroy Earth

Originally published on Live Science.

Brandon is the space / physics editor at Live Science. With more than 20 years of editorial experience, his writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. His interests include black holes, asteroids and comets, and the search for extraterrestrial life.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus