Scientists' 1st-ever view of sun's middle corona could sharpen space weather forecasts

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Recent telescope views shed new light on the sun's elusive middle corona that could prove beneficial to space weather forecasts.

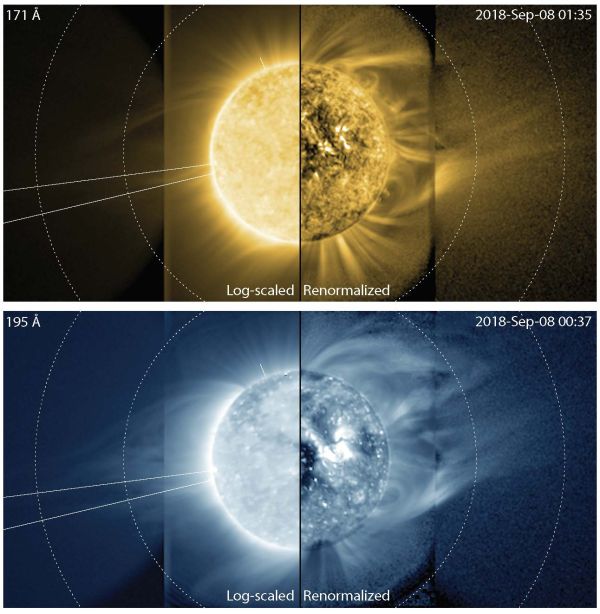

Using the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's (NOAA) GOES-17 satellite, researchers from the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES) captured the first-ever images of the sun's middle corona — also known as the sun's outer atmosphere — and the dynamics that trigger solar wind and the big eruptions dubbed coronal mass ejections, according to a statement from the NOAA's National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI).

"Our instruments focus on the sun, but not at the heights needed to see these events," Dan Seaton, lead author of the study and a scientist with NCEI and CIRES, said in the statement. "We were able to create a larger field of view and construct mosaic images of the sun showing the solar corona in extreme ultraviolet light, to answer questions about how the sun's outer atmosphere connects to the surface of the star."

Related: What's inside the sun? A star tour from the inside out

The images were taken by the Solar Ultraviolet Imager (SUVI) on the GOES-17 satellite in August and September of 2018. The solar photos capture views of the middle corona from each side of the sun and head on. Researchers pieced these different views together to create a larger composite image, revealing the structure, temperature and nature of extreme ultraviolet emissions from this region of the sun's outer atmosphere, which is generally more difficult to see, according to the statement.

The ultraviolet emissions released from the sun's corona are tied to space weather events like the steady stream of the solar wind and solar eruptions that can travel to Earth and technologies including radio communications, power grids and navigation systems. According to the study, the researchers identified the middle corona as the region of the sun's outer atmosphere that ultimately drives solar wind and big solar eruptions.

Images of the middle corona also revealed new clues about the connection between the complex magnetic structure of the inner corona and the outer corona, where the solar wind flows into the heliosphere — the vast bubble of space surrounding the sun. By combining a series of images from the SUVI, researchers were able to watch how plasma in the middle corona flows back and forth between the different regions of the sun's outer atmosphere and out into space.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We didn't think there was such a deep connection between these regions, but now we know they're interacting all the time," Seaton said in the statement.

In turn, their findings, published Aug. 2 in the journal Nature Astronomy, could help forecasters better detect and track solar eruptions, also known as coronal mass ejections (CMEs), that pose a potential threat to Earth.

"With our technique, we can capture the dynamic beginnings of coronal mass ejections and see how they're born out into the heliosphere," Seaton said in the statement. "That improves models of CMEs, opening the door to new science and leading to more accurate space weather forecasts."

Follow Samantha Mathewson @Sam_Ashley13. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus