NASA will fire 3 rockets directly at the solar eclipse on Saturday. Here's why.

NASA researchers plan to launch three rockets carrying scientific instruments toward the moon's shadow on Oct. 14, to study changes in the atmosphere brought about by the annular solar eclipse.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

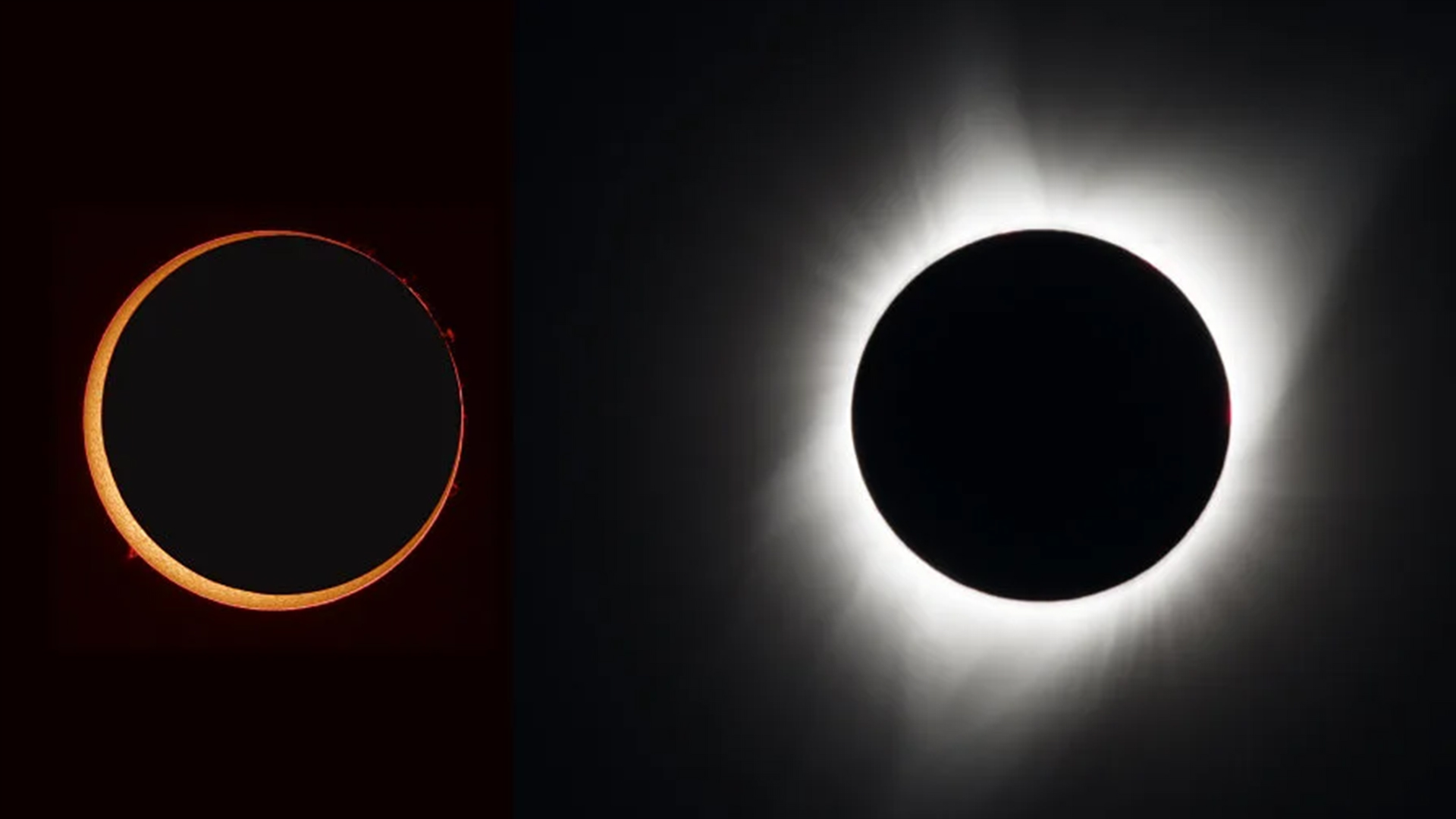

As millions of people across North, Central and South America tilt their heads skyward to watch the partial "ring of fire" solar eclipse tomorrow (Oct. 14), NASA engineers will celebrate the once-in-a-decade event in their own way: By firing rockets directly at the eclipse's shadow.

Don't worry — the sun, moon and everyone watching will be just fine. According to NASA, the planned launch of three scientific rockets from White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico is part of a purely scientific mission to study changes in Earth's upper atmosphere during the sudden plunge in daylight that eclipses bring.

Related: Where to buy solar eclipse glasses before the Oct. 14 'ring of fire' eclipse

At its peak, Saturday's eclipse will see roughly 90% of the sun's light blocked by the moon. We know from prior eclipses that this sudden drop in daylight can have some really strange effects on the planet, including rapid changes in temperature, wind patterns and even animal behavior. Less understood is how an eclipse affects the electrically-charged upper atmosphere, or ionosphere, which begins between 30 and 50 miles (50 to 80 kilometers) above Earth.

Here, the sun's ultraviolet radiation rips electrons away from atoms, forming a vast sea of charged particles throughout the day; at sundown, many of these electrons recombine into neutral atoms, until the sun's morning rays return and split them apart again. During the 2017 total solar eclipse over North America, scientists watched a speeded up version of this process play out when the moon completely blocked the sun's light for a few moments, causing "ripples" in the ionosphere as temperatures and ion density rapidly dipped, then rose again just after the eclipse's peak.

The combined air- and ground-based data will give APEP researchers an unprecedented view of atmospheric changes during an eclipse. The team will also recover and reuse the rockets to study the eclipse due to cross North America on April 8, 2024 — this time, launching from NASA's Wallops Flight Facility in Virginia, just outside the eclipse's path.

Following that, the team won't get another chance to shoot rockets at the moon's shadow until 2044, when the next total solar eclipse arrives.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Brandon is the space / physics editor at Live Science. With more than 20 years of editorial experience, his writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. His interests include black holes, asteroids and comets, and the search for extraterrestrial life.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus