Astronomers spot aurora on the sun for the 1st time

Scientists have spotted an aurora signal caused by electrons accelerating through a sunspot on our star's surface for the first time ever.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

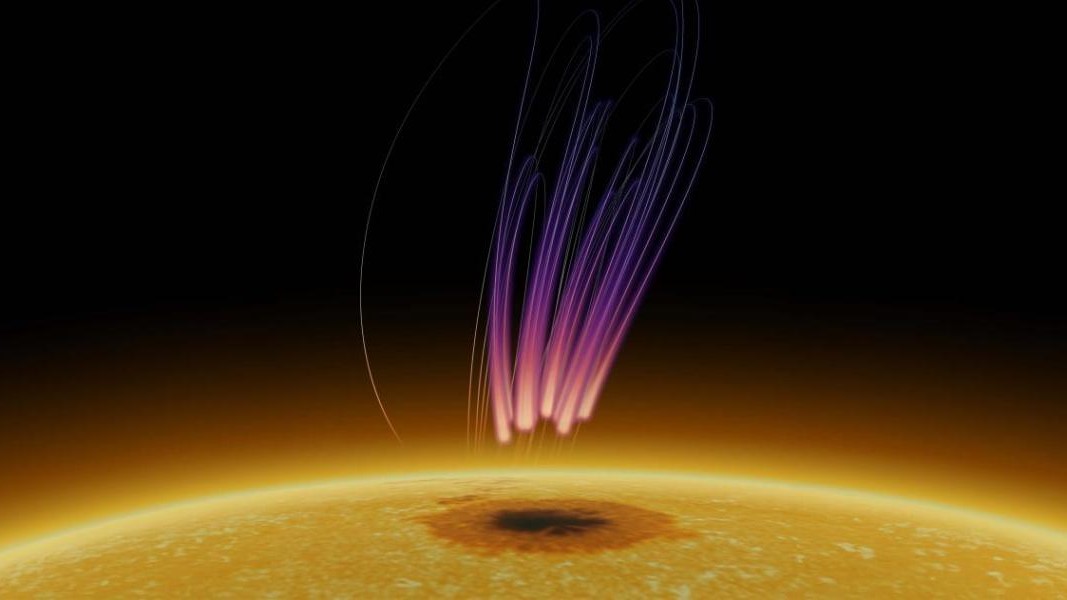

Scientists have spotted a stunning "aurora-like" display of crackling radio waves over the surface of the sun that is strikingly similar to the Northern Lights on Earth.

The solar lightshow took place roughly 25,000 miles (40,000 kilometers) above a sunspot — a magnetically warped dark patch on our star's surface. Astronomers on Earth detected the bursts of radio waves over the course of a week.

Scientists have detected aurora-like radio signals from distant stars in the past, but this is the first time they've seen a signal of this kind from our own sun. They published their findings Nov. 13 in the journal Nature Astronomy.

"This is quite unlike the typical, transient solar radio bursts typically lasting minutes or hours," lead author Sijie Yu, an astronomer at New Jersey Institute of Technology's Center for Solar-Terrestrial Research (NJIT-CSTR), said in a statement. "It's an exciting discovery that has the potential to alter our comprehension of stellar magnetic processes."

On Earth, auroras are the result of energetic solar debris zipping through the atmosphere near the poles,where the protective magnetic field is weakest, and agitating oxygen and nitrogen molecules. This causes the molecules to release energy in the form of light, tracing rippling curtains of color across the sky.

Solar debris is usually fired away from the sun when magnetic fields around sunspots knot into kinks before suddenly snapping. The resulting release of energy launches bursts of radiation called solar flares and explosive jets of solar material called coronal mass ejections (CMEs).

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

By pointing a radio telescope at a sunspot on our star's surface, the researchers detected an aurora-like emission above it, which they believe is the result of electrons from solar flares being accelerated along the sunspot's powerful magnetic field lines.

"However, unlike the Earth's auroras, these sunspot aurora emissions occur at frequencies ranging from hundreds of thousands of kHz [kilohertz] to roughly 1 million kHz — a direct result of the sunspot's magnetic field being thousands of times stronger than Earth's," Yu said. For comparison, a typical aurora on Earth emits light at frequencies between 100 to 500 kHz.

The researchers say their discovery has opened up new ways to study the sun's activity, and they have begun poring through archival data to find hidden evidence of past solar auroras.

"We're beginning to piece together the puzzle of how energetic particles and magnetic fields interact in a system with the presence of long-lasting starspots," study co-author Surajit Mondal, a solar physicist at NJIT, said in the statement. "Not just on our own Sun but also on stars far beyond our solar system."

Ben Turner is a U.K. based writer and editor at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus