Europe launches twin spacecraft to make daily solar eclipses in space. Here's what to know about Proba-3.

On Dec. 5, 2024 the European Space Agency's Proba-3 mission sent two spacecraft into orbit around Earth. By aligning the probes, researchers will create 6-hour-long mini eclipses, allowing the sun's atmosphere to be studied like never before.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

On Thursday (Dec. 5) the European Space Agency (ESA) launched a groundbreaking mission to make solar eclipses a daily occurence — in space, at least.

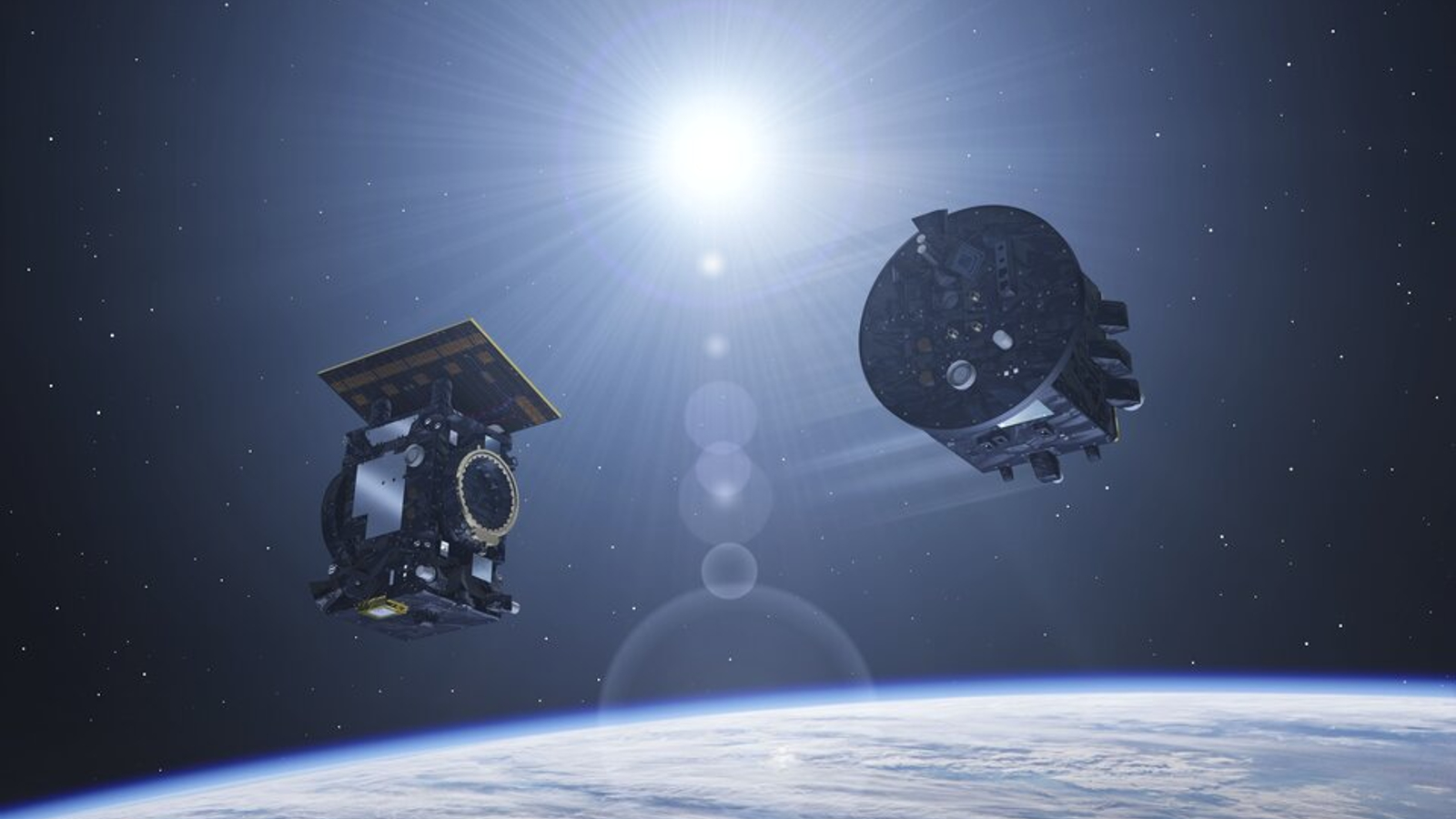

Known as Proba-3, the mission began by launching twin spacecraft into Earth orbit, where they will align with each other to create frequent, artificial eclipses in space. The unique mission will give researchers near-unlimited access to studying the sun's outer atmosphere, or corona, for the first time.

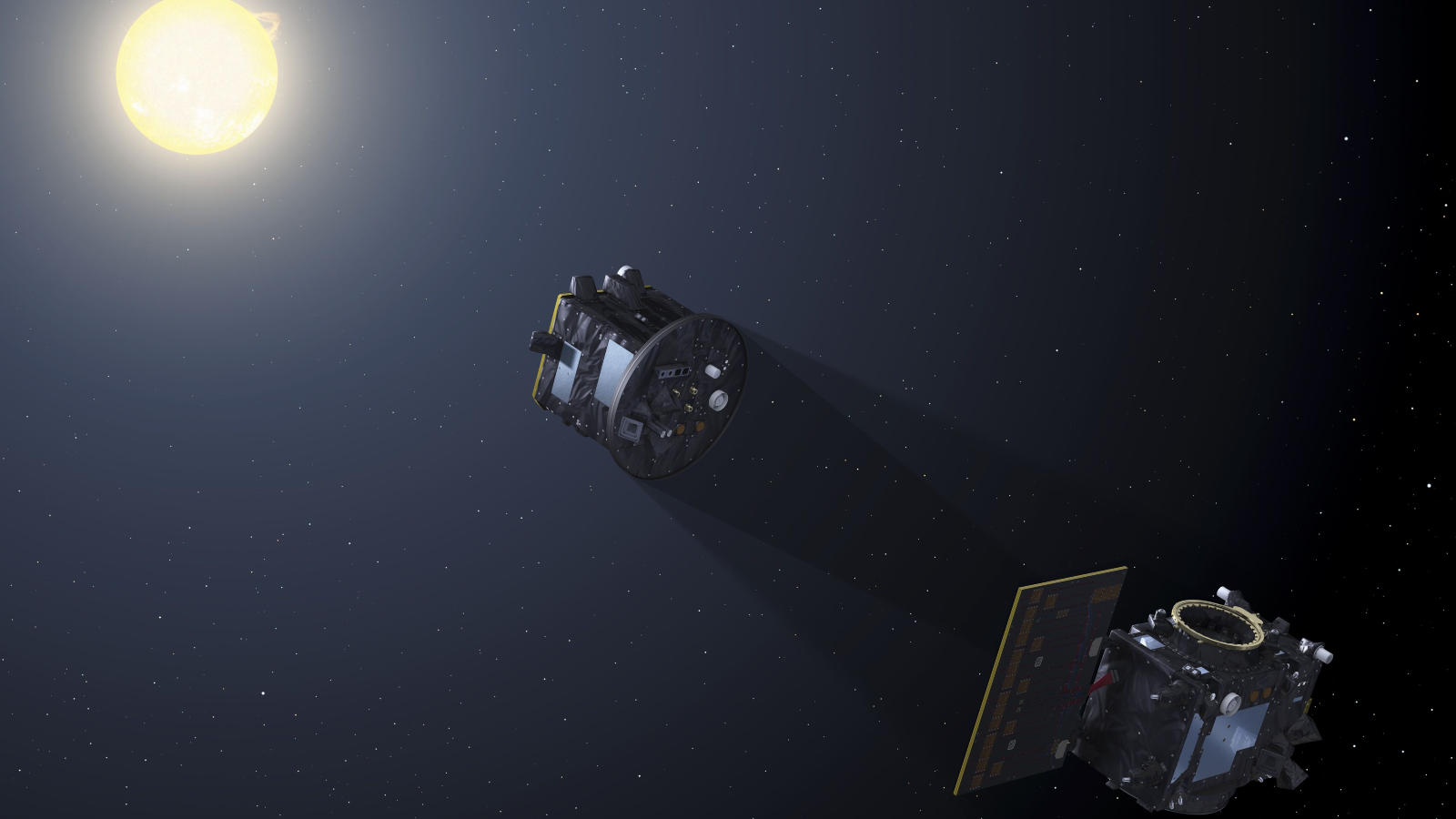

The Proba-3 mission involves a pair of probes known as Coronagraph and Occulter. When in orbit, Occulter will be able to position itself between Coronagraph and the sun so that it perfectly blocks out just enough sunlight to simulate terrestrial eclipses. In doing so, Coronagraph's camera will be able to focus on the corona, which appears as a swirling sea of wispy plasma lines when it is viewed in isolation from the rest of the sun.

The twin probes successfully launched from India's Satish Dhawan Space Centre at 16:04 local time, according to ESA. The pair is currently attached together, and will remain so throughout the initial commissioning phase of the mission, ESA added.

Once commissioned, it will take the two spacecraft around 19.5 hours to complete a single, highly elliptical (or stretched) orbit around Earth, and they will be in eclipse formation for six continuous hours every rotation. While they are forming an eclipse, the two spacecraft will be around 470 feet (144 meters) apart, which means they must be perfectly aligned for the maneuver to work properly. If the two probes are not in sync, Occulter's shadow could block light from reaching Coronagraph's solar panel array, thereby jeopardizing the spacecraft's power.

Related: Could we turn the sun into a gigantic telescope?

During terrestrial eclipses, the sun's corona becomes more visible to us on Earth than at any other time, which allows us to see things that would normally be hidden to us. For example, during the recent "ring of fire" eclipse that occurred above Australia on April 20, 2023, scientists could clearly see a gigantic cloud of magnetized plasma, known as a coronal mass ejection, as it exploded out of the sun.

However, terrestrial eclipses last only a maximum of around five to 10 minutes and happen just once or twice a year. The new mission will, therefore, exponentially increase the amount of high-quality data that researchers can analyze. Being able to see the corona in this much detail for prolonged periods every day will allow researchers to study how solar storms explode from the sun and how solar wind is generated, as well as to measure the sun's overall energy output.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Russell Howard, an astrophysicist and mission scientist for NASA's Parker Solar Probe, praised the ingenuity of this "unique project" and added that having access to the new data "will be spectacular."

The mission's launch coincides with the explosive peak in the sun's 11-year solar cycle, known as solar maximum. According to NASA and NOAA, solar maximum is well underway, and solar activity should remain strong for at least the next year. This should allow Proba-3 to start making discoveries right away.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus