There's another comet ATLAS in our solar system — and it just turned gold after a perilous dance with the sun

New photos show that the recently discovered comet C/2025 K1 (ATLAS) developed a surprising golden glow after reaching its closest point to the sun. Until now, the comet has gone under the radar, largely thanks to the more famous interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS.

New photos reveal that a recently discovered comet dubbed the "other ATLAS" has transformed into a spectacular golden ribbon after surviving a close approach to the sun — a journey that many experts believed would be the comet's doom.

The comet, called C/2025 K1 (ATLAS), was discovered in May by astronomers at the Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System (ATLAS), which scans the night sky for moving objects using telescopes in Hawaii, Chile and South Africa. The object has largely gone under the radar until now, mainly due to the recent hype around the interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS, which was discovered by ATLAS astronomers in early July, and Comet Lemmon, which has been clearly visible in the night sky over recent weeks.

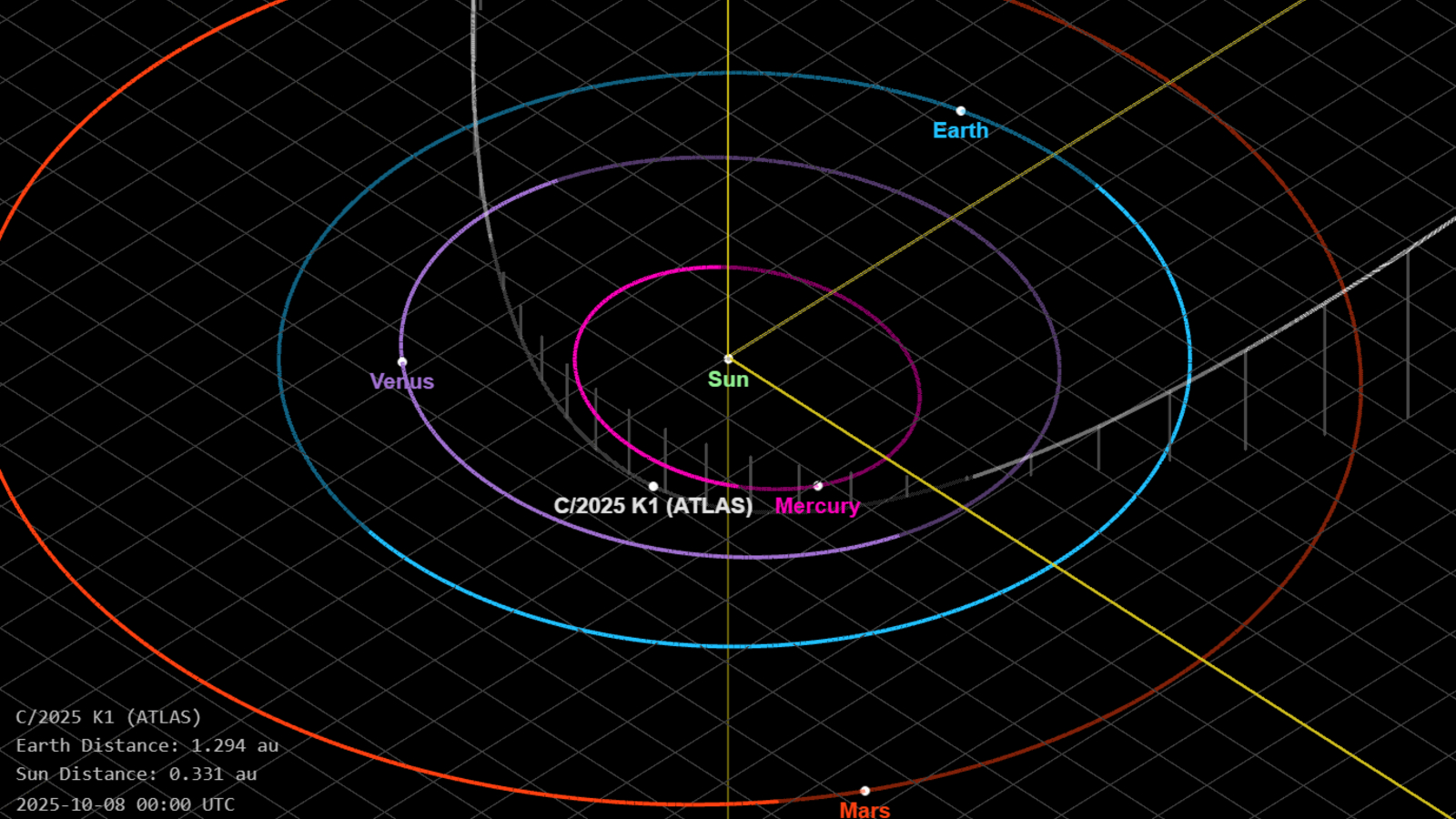

C/2025 K1 reached its closest point to the sun, or perihelion, on Oct. 8, coming within a minimum distance of 31 million miles (50 million kilometers) of our home star — around four times closer than 3I/ATLAS managed during its own perihelion on Oct. 29. Due to the intense gravitational strain from this close encounter, many experts believed that C/2025 K1 would be ripped apart, according to Spaceweather.com.

On Oct. 29, at the same time 3I/ATLAS achieved perihelion, astrophotographer Dan Bartlett snapped a stunning shot of C/2025 K1 from June Lake in California. The image shows the comet with a distinct golden glow and a long tail that looks as if it has been buffeted by the solar wind — similar to Comet Lemmon, which recently had its tail torn to pieces.

"This comet was not supposed to survive its Oct. 8th perihelion," Bartlett told Spaceweather.com. "But it did survive, and now it is displaying a red/brown/golden color rarely seen in comets." The same unique coloration was observed by at least two other photographers, in California and in Arizona.

Comets typically appear white because the sunlight they reflect contains all the wavelengths of visible light. However, when specific chemicals are present within the cloud of ice, gas and dust surrounding the comet, known as the coma, they can absorb specific wavelengths of light, causing the comet to shine with a different hue.

For example, several notable comets have turned green in recent years — including Comet Nishimura, the explosive "devil comet" 12P/Pons-Brooks and the aptly named "green comet" C/2022 E3 — due to the presence of either dicarbon or cyanide in their respective comas. Some comets can also turn blue if their comas contain carbon monoxide or ammonia, which may be happening to 3I/ATLAS, according to recent observations. However, the golden color of C/2025 K1 is much rarer.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In a recent blog post, astronomer David Schleicher, who has been studying C/2025 K1 from the Lowell Observatory in Arizona, wrote that the comet has a surprising lack of carbon-bearing molecules, such as dicarbon, carbon monoxide and cyanide. Only two other known comets have ever had fewer of these molecules, he wrote.

This depletion of carbon-bearing molecules is the most likely cause for the comet's gold coloration, but "we don't know exactly why," Spaceweather.com representatives wrote. But it could also have something to do with its recent solar flyby or its relatively low ratio of gas to dust, they added.

C/2025 K1 now has an apparent magnitude of 9, which is equally as bright as 3I/ATLAS following an unexpected brightening event that occurred during its flyby of the sun. Both objects are too dim to see with the naked eye, but they can be seen with a decent telescope or a pair of stargazing binoculars.

If you want to see it for yourself, C/2025 K1 is located between the constellations Virgo and Leo in the eastern sky, and it is most clearly visible shortly before sunrise, according to Spaceweather.com. It will reach its closest point to Earth on Nov. 25, meaning it will likely remain visible until early December.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus