Comet predicted to light up Earth's skies this fall may be falling apart

A new paper suggests that comet C/2023 A3, also known as Tsuchinshan-ATLAS, may completely break apart before it reaches its closest approach to Earth in October. If the comet does survive long enough to reach us, it should be bright enough to spot with the naked eye.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

An incoming comet that could be visible to the naked eye as it passes Earth later this year may be doomed to disintegrate before we get the chance to see it up close, a new study suggests. Recent observations hint that the comet has already begun fragmenting and could fall apart completely in the next few weeks or months. However, some experts disagree.

Astronomers at the Purple Mountain Observatory in China first spotted comet C/2023 A3, also known as Tsuchinshan-ATLAS, on Jan. 9 2023 and it was confirmed on Feb. 22 the same year, when NASA's Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System (ATLAS) spotted it barreling toward the sun. The comet's trajectory hints that this could be its first-ever close approach to the sun and that it may eventually be ejected from the solar system.

C/2023 A3 is due to reach its closest point to the sun, or perihelion, on Sept. 27 and could make its closest pass to Earth on Oct. 13, when it will be around 44 million miles (71 million kilometers) from our planet. If the comet wanders this close to Earth, it will be as bright as most stars in the night sky, making it possible for people to spot it with the naked eye for several weeks.

But in a new study, uploaded July 8 to the preprint server arXiv, study author Zdenek Sekanina — an astronomer at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory who has been studying comets for more than 50 years — argues that C/2023 A3 may meet its end before it reaches perihelion.

"The comet has entered an advanced phase of fragmentation, in which increasing numbers of dry, fractured refractory solids stay assembled in dark, porous blobs of exotic shape," Sekanina wrote in the paper. These fragments will eventually become "undetectable as they gradually disperse in space," he added.

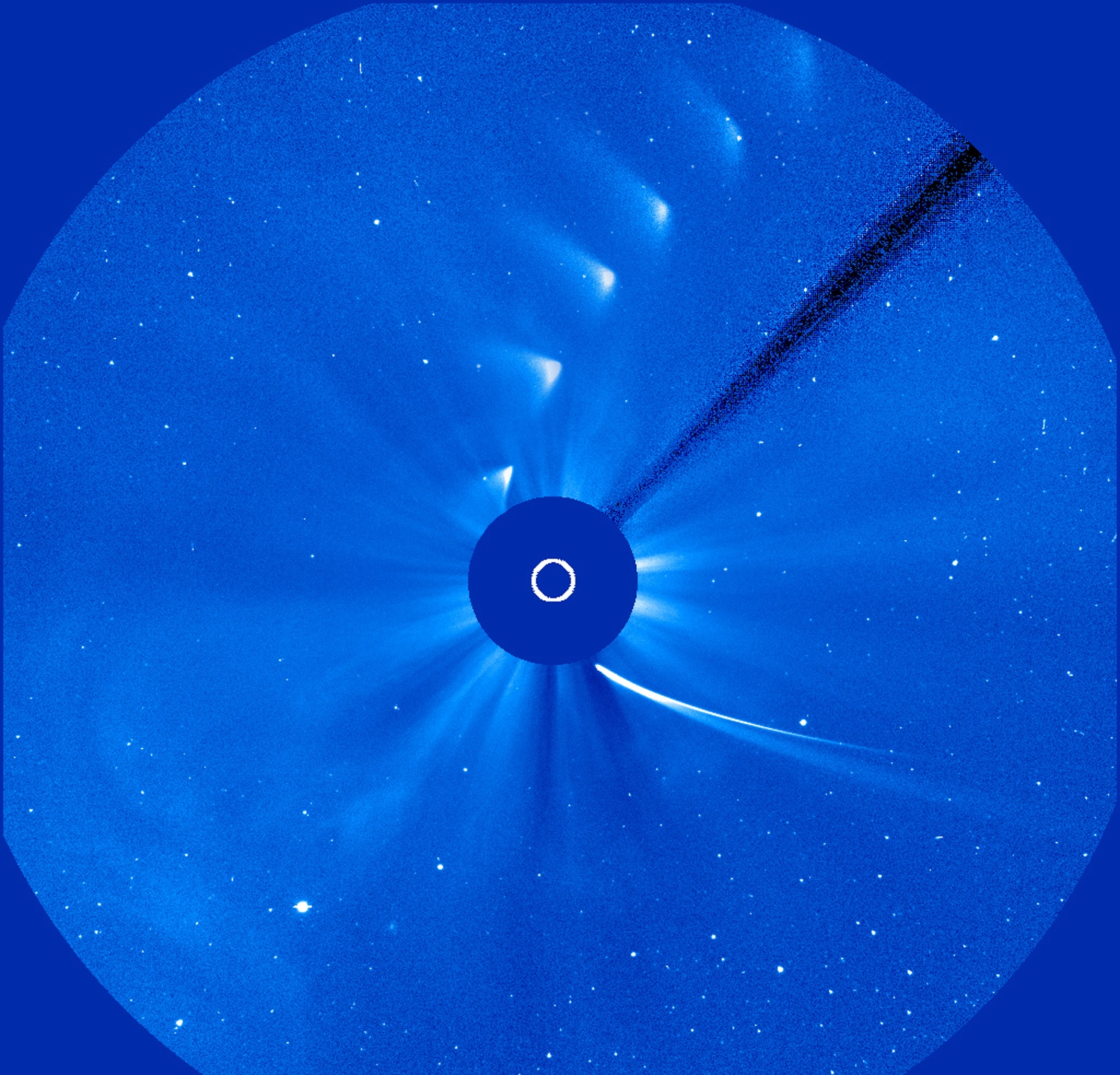

Large comets normally fragment at perihelion, as the sun's immense gravity tugs on the icy objects. This is what happened to comet ISON, which was violently ripped apart during a solar flyby in 2014, according to the European Space Agency.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Scientists previously hypothesized this would also happen to two other comets that recently passed by Earth: Comet Nishimura, which slingshotted around the sun in September last year; and Comet 12P/Pons Brooks, also known as the "devil comet," which survived its trip around the sun in April this year.

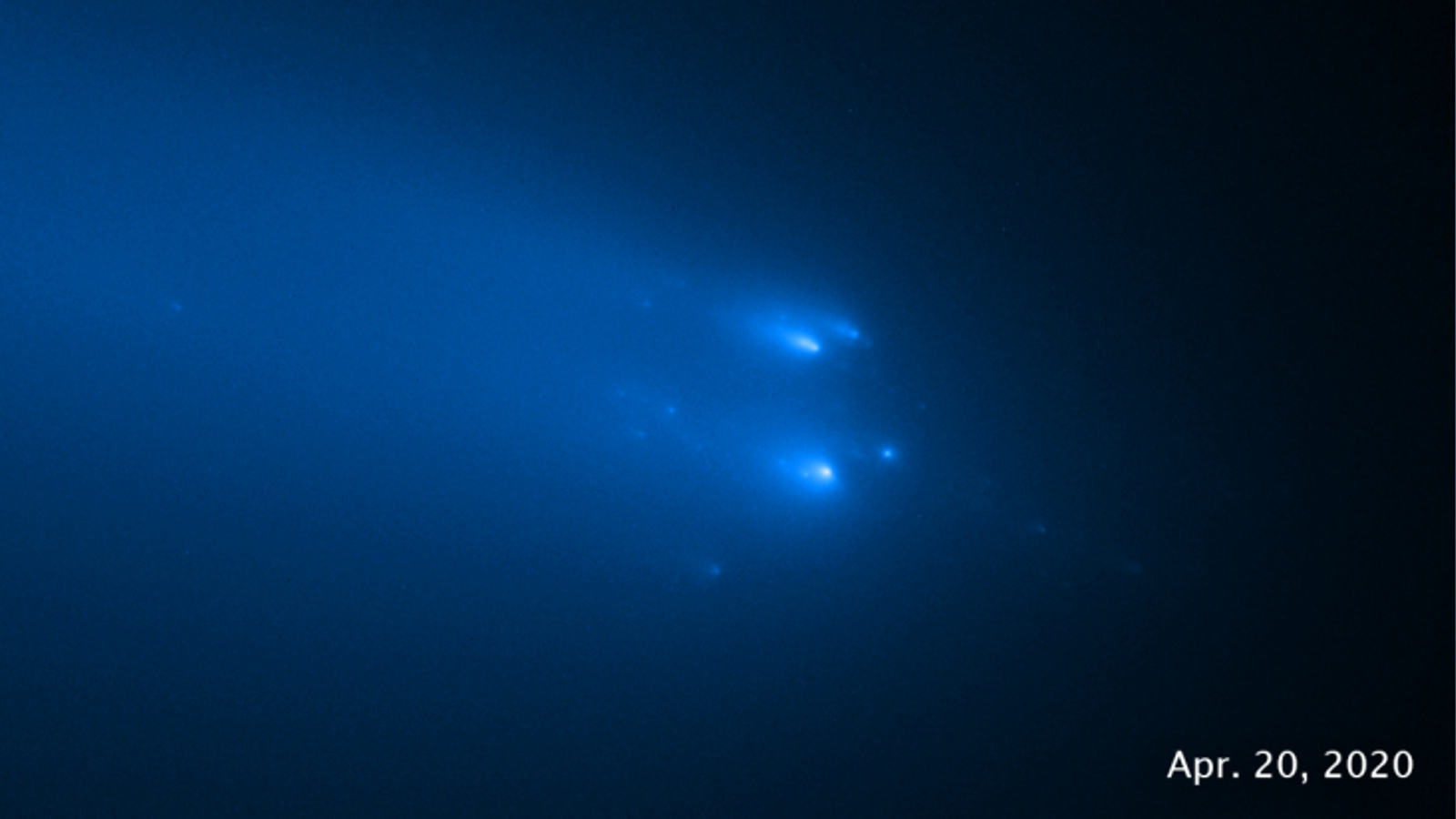

However, comets like C/2023 A3 can also fragment on approach to the sun as the increase in solar radiation puts pressure on previous fractures. This happened to comet C/2019 Y4, which spectacularly fell apart into dozens of pieces before its close approach in 2020, according to NASA.

In the new paper, Sekanina argues that several lines of evidence point to C/2023 A3's "inevitable collapse."

First, the comet has failed to brighten as it approaches the sun like most other comets do, meaning that its nucleus, or shell, may not be completely intact. Second, the comet's dusty tail is much thinner than it should be and has a "peculiar orientation," which also suggests the comet is not in one piece. Third, the comet seems to be experiencing "non-gravitational acceleration," which is most likely being caused by inner jets of gas that are pushing the nucleus apart.

However, not everyone agrees with Sekanina's observations.

"This doesn't look like a comet that is fragmenting to me," Nick James, an astronomer with the British Astronomical Association who was not involved in the study, told Spaceweather.com. "To use [the word] 'inevitable' in any prediction about a comet may be unwise," he added.

However, James noted that the new paper is "another good reason to observe this comet at every opportunity."

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus