Mutant 'daddy shortlegs' created in a lab

Researchers were able to 'switch off' the genes behind the arachnid's famously long legs.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Scientists have created "daddy shortlegs," a stunted version of the common household pest daddy longlegs, by suppressing the genes behind the arachnid's famously elongated limbs.

Daddy longlegs, also known as harvestmen, belong to the class Arachnids — a group of eight-legged invertebrates that includes spiders, scorpions, ticks, mites and horseshoe crabs. There are more than 6,500 species of daddy longlegs in the order Opiliones, each of which is characterized by flexible legs that are several times longer than the individual's body.

In a series of new experiments, a team of researchers mapped the entire genome of Phalangium opilio, the most common species of daddy longlegs, and isolated the genes responsible for their famous long legs. The researchers then turned off the long leg genes in developing embryos, creating individual arachnids with shorter, deformed legs.

Related: 10 amazing things scientists just did with CRISPR

"Our purpose was not just to shorten their legs just for the sake of it," lead author Guilherme Gainett, a graduate student at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, told Live Science. "We wanted to understand more about how these fascinating creatures evolved their alien way of locomotion and body plan."

Unlike true spiders, daddy longlegs don't use all eight of their legs for walking; instead, they use three pairs for locomotion and the remaining, and longest, pair, they wave around to feel their way around, Gainett added.

Mapping the genome

The researchers took two years to map all 580 million base pairs of the P. opilio genome, which is around one-sixth the size of the human genome, Gainett said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Once that was done, researchers searched the DNA map for genes likely to cause long legs, by comparing the P. opilio genome with the genomes of other insects, such as the fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster), in which scientists had already figured out which genes code for legs, Gainett said.

The comparison revealed two Hox genes — a group of related genes that code for specific body parts during embryonic development — known as Deformed (Dfd) and Sex combs reduced (Scr), that were tied to leg development in other species.

Switching off the genes

The researchers were confident that the Dfd and Scr genes played a role in the development of long legs in P. opilio. But it was not clear if both needed to be turned off, or if some combination was sufficient, to change leg shape and size, Gainett said.

Therefore, the researchers down-regulated these genes in developing embryos to see if the change would interfere with the development of their long legs.

To do this they used a process known as RNA interference, which is inspired by a process living cells use to ward off viruses. When viruses invade cells, a protein structure known as the RISC complex identifies the invaders' double-stranded RNA. The cell can then target and turn off the corresponding messenger RNA (mRNA), single-stranded RNA used to help transcribe or read genes, which viruses use to reproduce within the cell, Gainett said.

However, organisms also produce mRNA to create new proteins. So the scientists repurposed the RISC complex to silence the mRNA of the Dfd and Scr by disguising those genes as viruses.

"By synthesizing artificial double-stranded RNA matching your gene of interest and injecting it into the embryo, it is possible to interfere with the expression of that gene," Gainett said.

Deformed legs

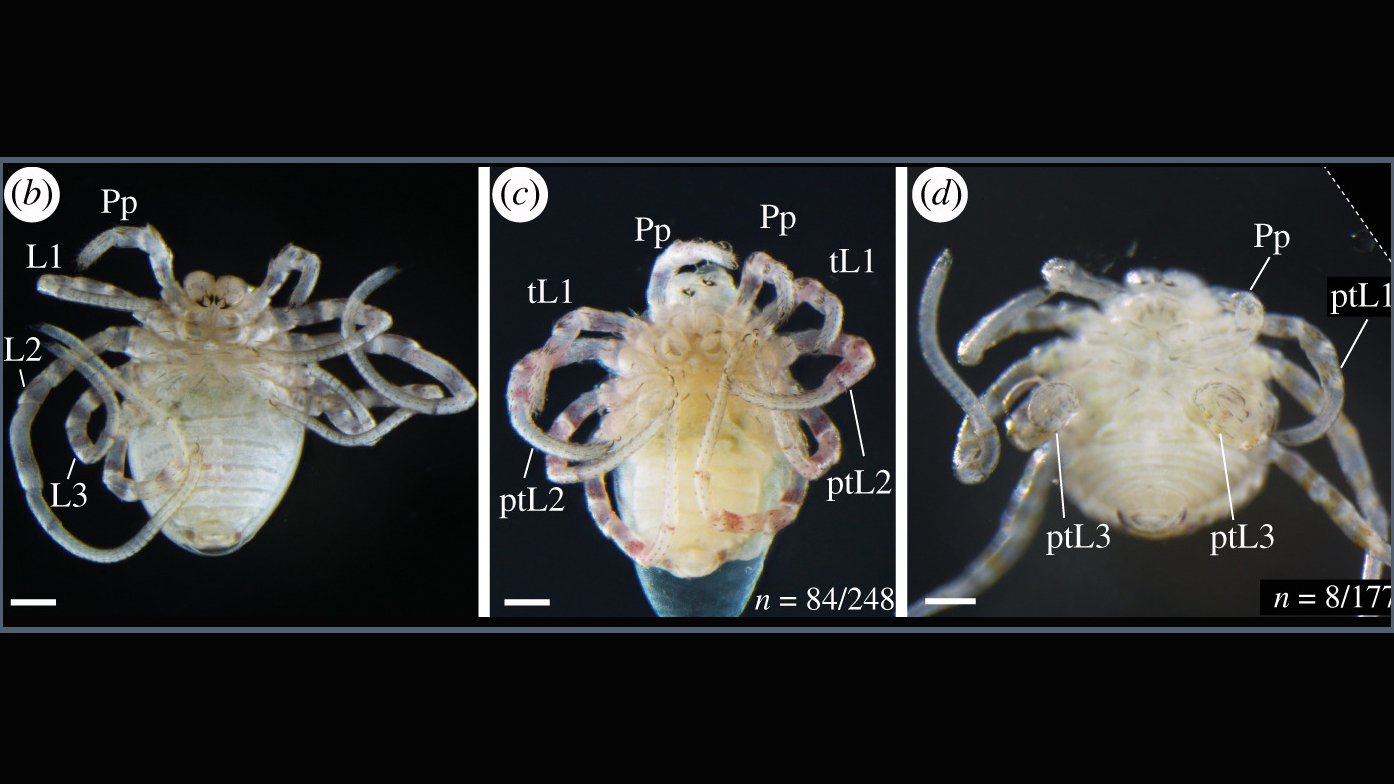

Switching off both the Dfd and Scr genes resulted in individuals with three pairs of shortened "walking" legs. They also changed shape.

"When the Hox genes are down-regulated these leg appendages transform into short food-manipulating appendages called pedipalps," Gainett said.

In addition to being much shorter than their normal legs, pedipalps have six segments, instead of the usual seven in regular legs; pedipalps also lack special joints known as tarsomeres, which give their legs the flexibility needed to properly move around and help sense the world around them, Gainett said.

However, not all the embryos' legs became shorter. The fourth pair of legs still grew to their usual length. "This is because the fourth pair of legs likely requires the input of a third Hox gene to set up their fate," Gainett said. "This is something that we are currently investigating," he added.

Some of the deformed embryos hatched with their shortened legs, but they all died before reaching adulthood, Gainett said.

Understanding arachnids

The findings help shine light on one of the most unusual body plans in the animal kingdom, Gainett said. "They [daddy longlegs] have been around for far longer than we have, around 400 million years, and to me, it is just amazing that we can make inferences about how animal morphologies evolved long ago and understand a bit more about the creatures we share our planet with," he added.

Gainett hopes that the findings could also lead to breakthroughs in understanding other arachnid body parts.

"I think future studies have the potential to clarify how other unique structures of arachnids are formed, such as the chelicera [fangs in spiders]," Gainett said.

The study was published online Aug. 4 in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Originally published on Live Science.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus