How little, furry mammals that scurried under dinosaurs' feet came to rule the world

A new book dives into the evolutionary history of mammals.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Shortly after dinosaurs got their start during the Triassic period, little furry mammals began scurrying underfoot, using their powerful teeth to chomp down on plants, insects and even — eventually — dinosaurs. But how did these warm-blooded creatures arise? How did they survive the giant asteroid that slammed into Earth and wiped out the nonavian dinosaurs 66 million years ago? And how are mammals doing today, given the challenges on the horizon?

In the book, "The Rise and Reign of the Mammals: A New History, from the Shadow of the Dinosaurs to Us," released on Tuesday (June 7) by Mariner Books, paleontologist Steve Brusatte answers these questions and more. Few are better poised to tell this tale than Brusatte, chair of paleontology and evolution at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland, whose first book, The New York Times bestseller "The Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs: A New History of a Lost World" (Mariner Books, 2018), connected readers with the diversity of scientists and their myriad discoveries about the dinosaur age.

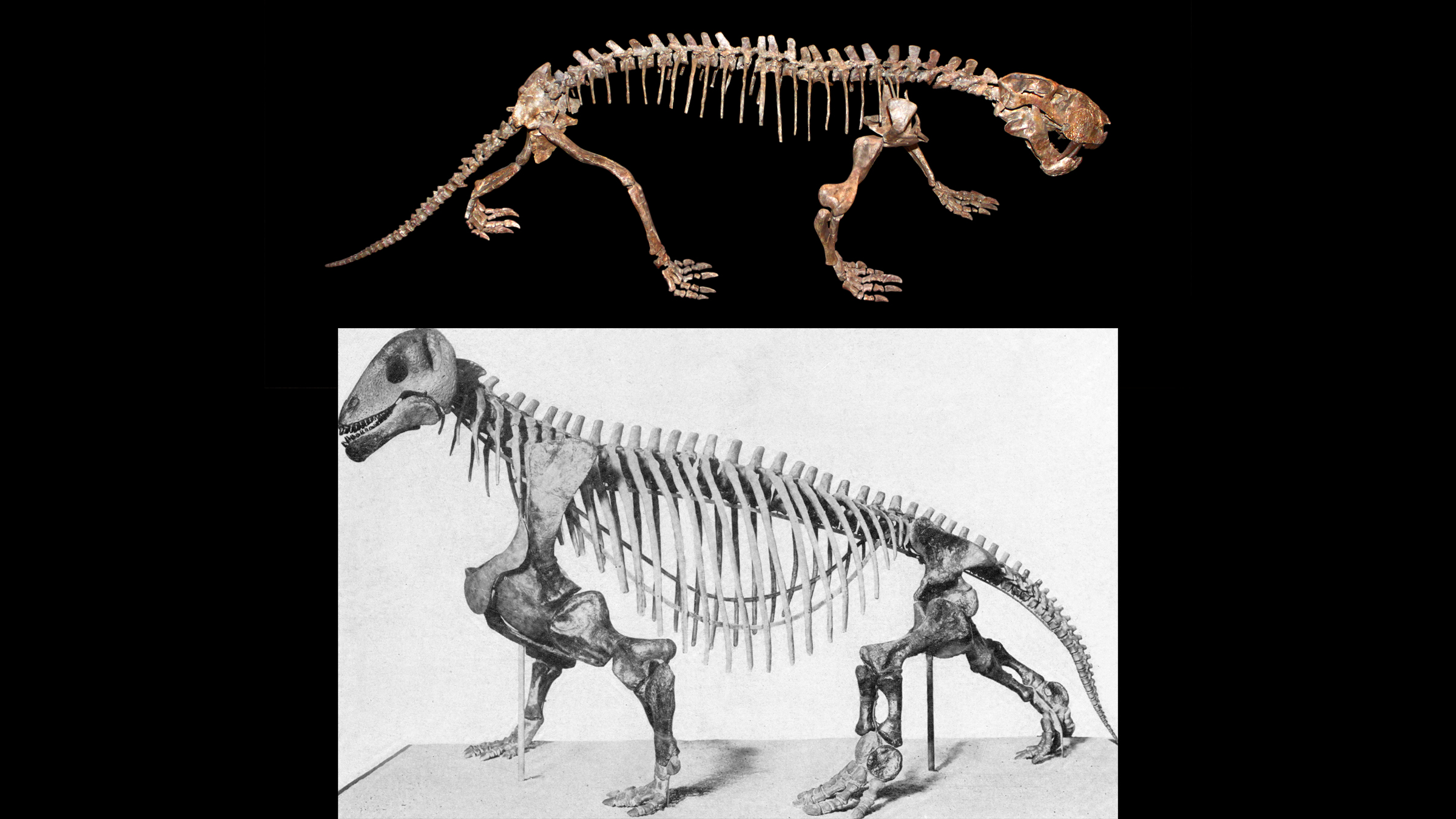

In his new book, Brusatte dives into the mammalian lineage dating back to the synapsids, a bizarre group of animals that lived during the Carboniferous period (359 million to 299 million years ago) that eventually evolved into the mammals. He traces the evolution of mammals up to the present day, sharing quirky facts (did you know that mammals' ear bones were once part of the jaw?) and introducing readers to the scientists who have made the study of mammals what it is today.

But don't take it from us. You can learn more about his new book from Brusatte himself, in an email Q&A with Live Science about his work. Brusatte's responses have been lightly edited for clarity.

Related: How long do most species last before going extinct?

Your new book is about mammals, so I have to ask: What happened to dinosaurs? You've always been known for your remarkable research on dinosaurs and you're even the paleontology advisor for "Jurassic World: Dominion" [Universal Pictures, 2022] Why did mammals grab your attention?

I love dinosaurs and always will be fascinated by them. I began my career as a dinosaur researcher and spent most of the last two decades working on them. But the more I've worked on dinosaur history — as I've followed them from their origins, to their evolution of colossal size, to their extinction — I naturally started to wonder what happened next. How did mammals take over from the dinosaurs? And ultimately I've learned it's as fascinating a story as the story of dinosaur evolution. After all, we are mammals. So this is our story: the tale of our deepest origins, of our ancestors, of how our kin have survived over 325 million years, of everything the Earth and the cosmos have thrown at us.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Mammals have a long history. Before animals evolved into mammals, what were some pre-mammals like and when did they live?

The mammal story goes back to about 325 million years ago, during the Carboniferous period, a humid realm of coal swamps, the time of the first jungles, an age where dragonflies were the size of pigeons and millipedes bigger than humans. It was in these swamps that a nondescript scaly creature split into two. One side of the family tree would eventually become lizards, crocodiles, dinosaurs and birds. The other lineage evolved a big hole behind the eye to anchor strong jaw muscles. These were the synapsids. They would eventually become mammals.

These animals leading to the mammal lineage developed traits associated with today's mammals, such as hair, warm-bloodedness (endothermy), and strong jaw muscles and bites. How did these adaptations and others help them survive and thrive?

The early synapsids had to endure a lot. They originated in the humidity of the coal swamps; then the jungles collapsed and much of the Earth became a scorching desert, as all of the land masses smashed together into the supercontinent of Pangea. Then, there was a devastating mass extinction — the worst period of mass death in Earth history — about 252 million years ago, when enormous volcanoes erupted in Siberia and caused global warming.

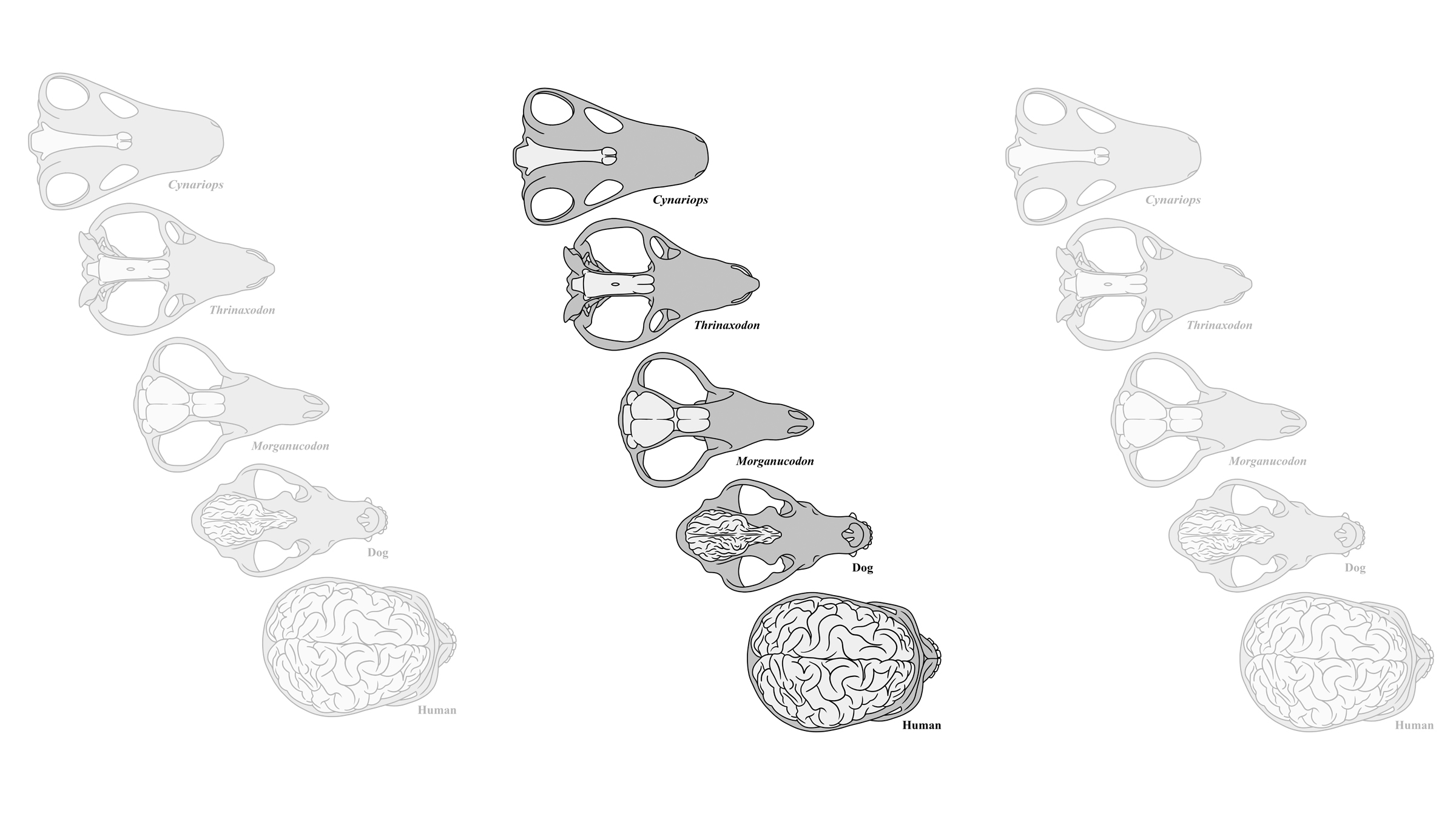

Through it all, the synapsids persisted and adapted. The evolved hair to keep their bodies warm. They became warm-blooded, so they had an internal furnace that controlled their body temperatures, rather than relying on the fickle whims of the environment. Their jaw muscles became massive, their teeth morphed from the simple steak knives of their ancestors into an array of canines, incisors, premolars and molars that could grab, slash, pulverize and chew their food. They developed expansive brains, and keen intelligence and sharp senses of smell and hearing. All of these things helped them better adapt than their ancestors to their environment and survive the ups and downs of their early history.

Related: What's the first species humans drove to extinction?

What's the earliest known mammal on record? What made it special that set it apart from all its pre-mammal relatives?

The first proper mammals lived around 225 million years ago in the Triassic period, on the supercontinent of Pangea. These were small, almost forgettable creatures, and if you saw one, you would probably just think it was a mouse. They seemed especially meek in comparison to the other animals evolving alongside them, at the same time: dinosaurs.

But don't let the small size of the mammals fool you. They were smart, fast, and adaptable. The key thing that set them apart from their ancestors was their simplified jaw. Whereas their ancestors had many small bones in their jaws, mammals reduced it to just one bone, the dentary. A single anchor for all of the teeth and all of the jaw muscles. Perfect for strong bites. Perfect for bites that can be carefully orchestrated to subdue prey and chew food. And what happened to those extra jaw bones that no longer had any use in feeding? They got tiny and moved into the ear, where they helped these mammals — and their descendants, like us! — deliver sounds from the eardrum to the cochlea. This is why we hear so well compared to most other animals.

For hundreds of millions of years, early mammals were small, shrew- to possum-size creatures. Why were they so little and when did mammals finally get big?

Mammals lived alongside the dinosaurs for over 150 million years, in the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceous. During all of this time, as far as we know, no mammal ever got larger than a badger. The dinosaurs kept them small. There was no room for mammals to get big, so they were relegated to the shadows. But they made the underworld their own. They diversified into countless species: scurriers, climbers, diggers, swimmers, even gliders with wings of skin. These early mammals were so good at living incognito that they kept the dinosaurs from becoming small. There never was a T. rex the size of a mouse, a Brontosaurus the size of a rat. That's because mammals seized those niches and never let go.

Mammals arose during the dinosaur age, which is crazy to imagine. How did the two interact, according to fossil evidence?

Dinosaurs kept the mammal small. Mammals kept the dinosaurs big. It was largely an evolutionary equilibrium for many tens of millions of years. But there is one stunning fossil from China, of a Cretaceous-aged mammal called Repenomamus, which is about the size of a lapdog. It was buried so quickly and turned to a fossil so rapidly that the remnants of its last meal were preserved in its stomach: dinosaur bones. This mammal ate baby dinosaurs for breakfast! Some dinosaurs would have lived in fear of mammals!

Related: How would Earth be different if modern humans never existed?

How on earth did mammals survive the asteroid that slammed into our planet 66 million years ago?

Sixty-six million years ago, an asteroid the size of Mount Everest was randomly hurtling through the heavens, and just so happened to make a beeline for the Earth. It impacted with the force of over one billion nuclear bombs. It punched a hole in the crust over 100 miles [160 kilometers] wide, which is a crater we now see in Mexico.

This was the worst single day in the history of life, of that I'm convinced. Tsunamis, earthquakes, wildfires, winds, dust blocking out the sun, forests dying, ecosystems collapsing. The dinosaurs couldn't cope, and all died except for a few birds. Mammals survived: yes, of course. But what most people don't realize is that mammals almost went the way of the dinosaurs. We think that around 90% of all mammals died. Only a few plucky survivors made it through. These were some mammals that were small, so they could burrow and hide easier, and they were omnivorous, so they could eat a variety of foods. Among them was one of our ancestors. If it didn't make it through the carnage of the asteroid, we would not be here having this conversation.

Once the dinosaurs went extinct (except for birds, of course), what types of mammals evolved?

Imagine yourself in the tiny, furry feet of our mouse-sized ancestor that survived the bedlam of the asteroid. All of a sudden, the world was an empty place. T. rex was gone. Triceratops was gone. Ecosystems were wide open. Opportunities were abundant. The mammals immediately took advantage. Remember that during the 150+ million years they lived alongside dinosaurs, no mammal ever got larger than a badger. Then, within a few hundred thousand years of the dinosaurs dying, there were mammals the size of pigs! Within a million years or so, mammals the size of cows! And from these mammals came many of our most familiar cousins: horses, dogs, primates, bats and whales.

What do you think is one of the weirdest, now-extinct mammals?

There were once woolly elephants and rhinos, armadillos the size of Volkswagens, deer with antlers larger than a dining room table, strange beasts called chalicotheres that looked like an unholy hybrid between a horse and gorilla, "thunder beasts" called brontotheres with battering-ram horns, rhinos that had no horns but weighed around 20 tons [18 metric tons] — the biggest mammals to ever live on land — pug-faced giant kangaroos and wombats in Australia that weighed three tons [2.7 metric tons]. All of these things are now extinct.

Some of them, our human ancestors would have met, and interacted with, and hunted. You will meet all of them in my book. But if you made me choose the single wackiest extinct mammals, I would go with the giant ground sloths of the ice age. Sloths today are small and cuddly. They're lazy. They're cute. But only about 10,000 years ago there were sloths that stood over 10 feet [3 m] tall, with claws that looked like those of Edward Scissorhands. They could have peered into a second story window or dunked a basketball without even trying. How does it get any weirder than that?

Related: When humans are gone, what animals might evolve to have our smarts and skills?

When did the first primates come into the picture and what were they like?

No more than about 100,000 years after the asteroid that killed the dinosaurs, we start to find tiny teeth in the fossil record. They have gentle cusps instead of sharp peaks or ridges — perfect for eating fruits. They are called Purgatorius, and they are the oldest primate. It seems that primates were one of the first mammal groups to take advantage of the death of the dinosaurs to diversify and spread widely.

But, there is evidence from DNA that primates may have a longer history. They — or, I should say, we! — have so many mutations in our DNA that if we back-calculate based on known rates of DNA change in the present-day, we would predict that primates actually originated alongside the dinosaurs, back in the Cretaceous. But we haven't found their fossils yet. Is that because the DNA evidence is wrong? Or have we just not looked for fossils in the right places? I suspect the latter — and I think that whoever finds the first true Cretaceous primate will become a very famous paleontologist.

Let's discuss the human lineage. What environmental and climate changes were going on as early humans evolved?

In the book, I try not to focus on humans. I don't want to make it all about us. After all, we are one of many sublime groups of mammals that have evolved over time. Whales became the largest animals to ever live — and today's blue whales are larger than submarines! Bats turned their arms into wings and began to fly. Elephants and rhinos supersized their bodies and evolved the most remarkable teeth and tusks. And the list goes on. So, I don't want to make it seem like humans are the inevitable culmination of mammal evolution, that all 325 million years of synapsid history was a backstory that neatly led to us. That is too simple of a story. But let's also face it, humans are remarkable. We have evolved huge brains, consciousness, the ability to work in groups, the ability to shape the world in so many ways, even the ability to domesticate and clone other mammals.

Our human journey started somewhere between 5 and 7 million years ago, when our ancestors split from other apes that would eventually evolve into chimpanzees. We began to walk upright before evolving massive brains and the ability to make tools from stones. And all of this was happening as climate was changing, as forests were shrinking in Africa — our ancestral homeland — and being replaced by grasslands. Or so the story goes. Although that turns out to be a little too simple too, and the real story is much richer, more complex, more fun. And you'll have to read the book to find out!!

Related: Can nonhuman animals drive other animals to extinction?

Humans are now at a crossroads, especially with human-caused climate change. Based on what we know from mammal fossils from past periods of climate tumult, what might happen to mammals going forward?

Mammals are currently at their — our — most precarious point since staring down the asteroid 66 million years ago. And although I hate to say it, it's all because one species of mammal has had such a detrimental effect on the other 6000+ species of mammals: us. We are changing the world so quickly. We hunt, we clear land, we turn forests into farmland, we pump greenhouse gases into the atmosphere that warm the planet, and so much more. Many of the charismatic ice age "megafauna," like woolly mammoths and saber-toothed tigers, probably died in large part because of us — because we hunted them, destroyed their habitats, broke up their populations.

Since the time Homo sapiens began marching across the globe, at least 350 mammal species have died — about 5% of all mammals. That may not seem like a large number, but if we continue at this pace, half of all mammals may be gone before too long. There are a lot of ifs there. I don't want to sound too pessimistic, or seem too confident about the future, which is hard to predict.

But what I do know is this: we humans evolved big brains, remarkable intelligence, the ability to work together. We know what we are doing to our planet, and we can come up with solutions. Mammoths and sabertooths and the countless other extinct mammals never had the same powers, either to alter the world or ameliorate it. We do. It is our choice what to do next.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus