'Potentially hazardous' asteroid that recently zipped past Earth is an elongated weirdo with an odd rotation

An asteroid that flew precariously close to Earth in early February has an extremely unusual shape and rotation for an object of its kind, new NASA research has shown.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

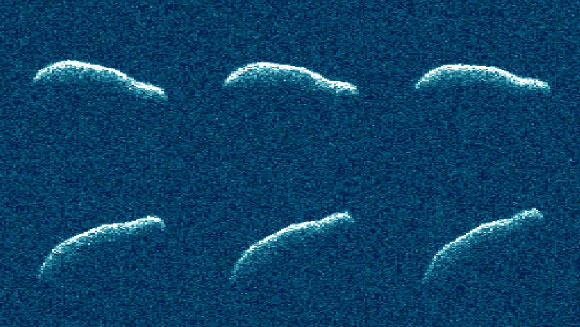

Astronomers recently got an up-close look at a "potentially hazardous" asteroid as it whizzed safely past Earth, and what they saw caught them by surprise: The space rock is unusually elongated for an asteroid and is spinning much more slowly than expected.

The asteroidal anomaly, known as 2011 AG5, was discovered in January 2011 by the Mount Lemmon Survey using a telescope based near Tucson, Arizona. The space rock made headlines at the time because researchers predicted that the asteroid's orbit around the sun, which takes around 621 days, could put it on a devastating collision course with Earth in 2040. But follow-up observations in 2012 revealed that its orbit had been majorly miscalculated and that it poses no real threat to our planet.

On Feb. 3, 2023, the asteroid passed within about 1.1 million miles (1.8 million kilometers) of Earth, or almost five times the distance between Earth and the moon. Its close flyby gave astronomers the chance to properly scan it for the first time.

Using a powerful 230-foot-wide (70 meters) Goldstone Solar System Radar antenna dish at NASA's Deep Space Network facility in southern California, researchers captured several images of the asteroid. The fuzzy pictures revealed that 2011 AG5 is 1,600 feet (500 m) long and about 500 feet (150 m) wide — about the size of the Empire State Building, according to a statement from NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL).

"Of the 1,040 near-Earth objects observed by planetary radar to date, this is one of the most elongated we’ve seen," Lance Benner, a principal scientist at JPL who helped lead the observations, said in the statement. Most of the scanned space rocks that have whizzed by Earth are much more rounded, he added.

The researchers do not want to speculate why 2011 AG5 is such a weird shape until they have had longer to study the new data, Benner told Live Science in an email.

Related: Why are asteroids and comets such weird shapes?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The radar scans also enabled researchers to calculate the asteroid's spin, revealing that it takes around 9 hours for the oblong object to complete a single rotation. This is a much longer rotational period than most asteroids, researchers wrote in the statement, and may be influenced by the space rock's unusual shape. But it is unclear exactly why the asteroid is spinning so slowly.

The new images also showed subtle dark and lighter patches several feet across on the asteroid's surface, which may indicate that there are multiple small-scale surface features littered across the asteroid. But what they might be remains a mystery.

The researchers hope that the additional data about the asteroid's trajectory collected by the new radar scans could narrow down where it will be in the future, which could help explain its unusual properties.

"These new ranging measurements by the planetary radar team will further refine exactly where it will be far into the future," Paul Chodas, the director forNASA's Center for Near Earth Object Studies (CNEOS) at JPL, said in the statement. This will increase our chances of learning more about this bizarre space rock, he added.

Although 2011 AG5 will not collide with Earth, it is expected to pass much closer — within 670,000 miles (1.1 million km) of our planet — when it returns for its next flyby in 2040. Any asteroid that passes within 4.7 million miles (7.5 million km) of Earth is classed as a "potentially hazardous asteroid," according to NASA, so it is important to keep an eye on them.

Editor's note: This article was updated on Feb. 22 at 9:25 a.m. EST to correct an error in the caption of the radar dish image and clarify why researchers have not yet speculated on the reason for the asteroid's odd shape.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus