What happens if you skydive through a cloud?

What it's like to skydive through a cloud depends in part on the type of cloud, but regardless, you'll likely end up cold and wet.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Even if you don't crave the adrenaline rush of adventure sports, perhaps, while flying on an airplane, you've wondered what it might be like to reach out and touch the clouds. Or, during a particularly bumpy descent, maybe you've been thankful to be inside the cabin and not out on the wing.

So what would it be like to pass through those clouds, as skydivers do, exposed to the elements?

This experience of falling through a cloud will vary depending on the cloud type, your protective gear and the weather conditions, which collectively result in conditions that can leave you soaking wet, freezing, or even unconscious, according to current and historical accounts.

Related: Why don't hurricanes form at the equator?

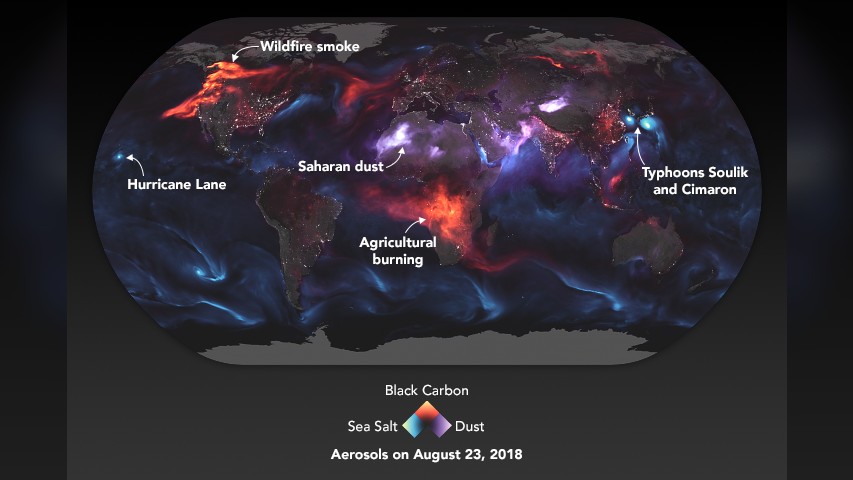

Clouds form when water molecules condense around particles in the air, called aerosols, and the nature of those particles affects the type and size of the resulting clouds. But according to Marilé Colón Robles, an atmospheric scientist at the NASA Langley Research Center in Virginia who studies clouds, "not every aerosol is created equal."

Certain natural aerosols, such as dust, typically prompt the formation of ice particles, while sea spray precipitates water molecules. Scientists have also experimented with seeding the atmosphere with artificially-introduced aerosols, including silver or lead iodide, to generate bright, dense clouds that reflect incoming solar radiation away from Earth or induce rain and snow.

Because skydivers jump from an altitude of 13,000 feet (4,000 meters), they're most likely to encounter stratus and cumulus clouds — the thick blanket of an overcast day and the pillowy, flat-bottomed clouds that mark an otherwise sunny afternoon, respectively. Both types are made up mostly of water molecules, and when they occur at elevations higher than 6,500 feet (1,980 meters), they're called altostratus and altocumulus clouds to designate their position in the atmosphere.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Ryan Katchmar, a Utah-based skydiving instructor with more than 10,000 jumps to his name, stressed that people should not skydive through clouds intentionally. If you can't see where you're going, there's no way to track potential hazards, including other skydivers or aircraft. But, he told Live Science, it does sometimes happen. "While we will try to dodge our way through clouds, sometimes you miss your window" and end up passing through, Katchmar said.

"Sometimes it doesn't feel like anything," he added. "You go into a white room, and then you pop out the bottom. But if they're dark, thick or dense clouds, it'll feel like a bit of a speed bump, and you'll come out soaking wet." He likened the sensation to how the air feels in very humid regions, "but cool and refreshing."

Katchmar has also encountered unexpectedly cold conditions, such as hail pinging off of his goggles. For this reason, jumpers often cover up to avoid exposure injuries. On a recent jump in Utah, as Katchmar was filming another skydiver, he noticed that the woman's nose and cheekbones were turning white as the divers fell. "When we went through the cloud, ice formed on us," he said.

The most extreme cases of skydiving in poor weather have involved thunderstorms. Inside a storm cloud, warm air can rise at speeds of over 100 mph (160 km/h), but at high elevations, those particles feel the pull of gravity and descend as rain or hail. Plus, most lightning that occurs during storms strikes within or between clouds, Colón Robles told Live Science. "So, in addition to being launched into space, you'll be in the mecca of all the lightning strikes," she said.

Only two people are known to have survived such a trip through a lightning storm-bearing cloud. In 1959, U.S. Lt. Col. William Henry Rankin ejected from his fighter jet in rough weather and spent 40 minutes being churned around inside a storm cloud — suffering frostbite and nearly drowning — before being spit out a few hundred feet from the ground and crash-landing into a tree. Decades later, in 2007, German paraglider Ewa Wiśnierska was unintentionally sucked into a thunderhead while training for the paragliding world championship. She lost consciousness due to a lack of oxygen and landed several hours later about 37 miles (60 km) away.

If you have no interest in experiencing terminal velocity for yourself, there's another way you can move through a cloud, simply by walking. "Fog is a stratus type cloud, just on the ground," Colón Robles said. That cool, dense air gives you a taste of what skydivers face as they plummet toward Earth.

Amanda Heidt is a Utah-based freelance journalist and editor with an omnivorous appetite for anything science, from ecology and biotech to health and history. Her work has appeared in Nature, Science and National Geographic, among other publications, and she was previously an associate editor at The Scientist. Amanda currently serves on the board for the National Association of Science Writers and graduated from Moss Landing Marine Laboratories with a master's degree in marine science and from the University of California, Santa Cruz, with a master's degree in science communication.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus