Jurassic pliosaur 'megapredator' was a giant 'sea murderer'

The earliest pliosaur 'megapredator' helped rule the oceans 170 million years ago during the age of dinosaurs.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A newfound member of a "dynasty" of pliosaur megapredators was at the top of the ocean food chain for 80 million years, a new study reveals.

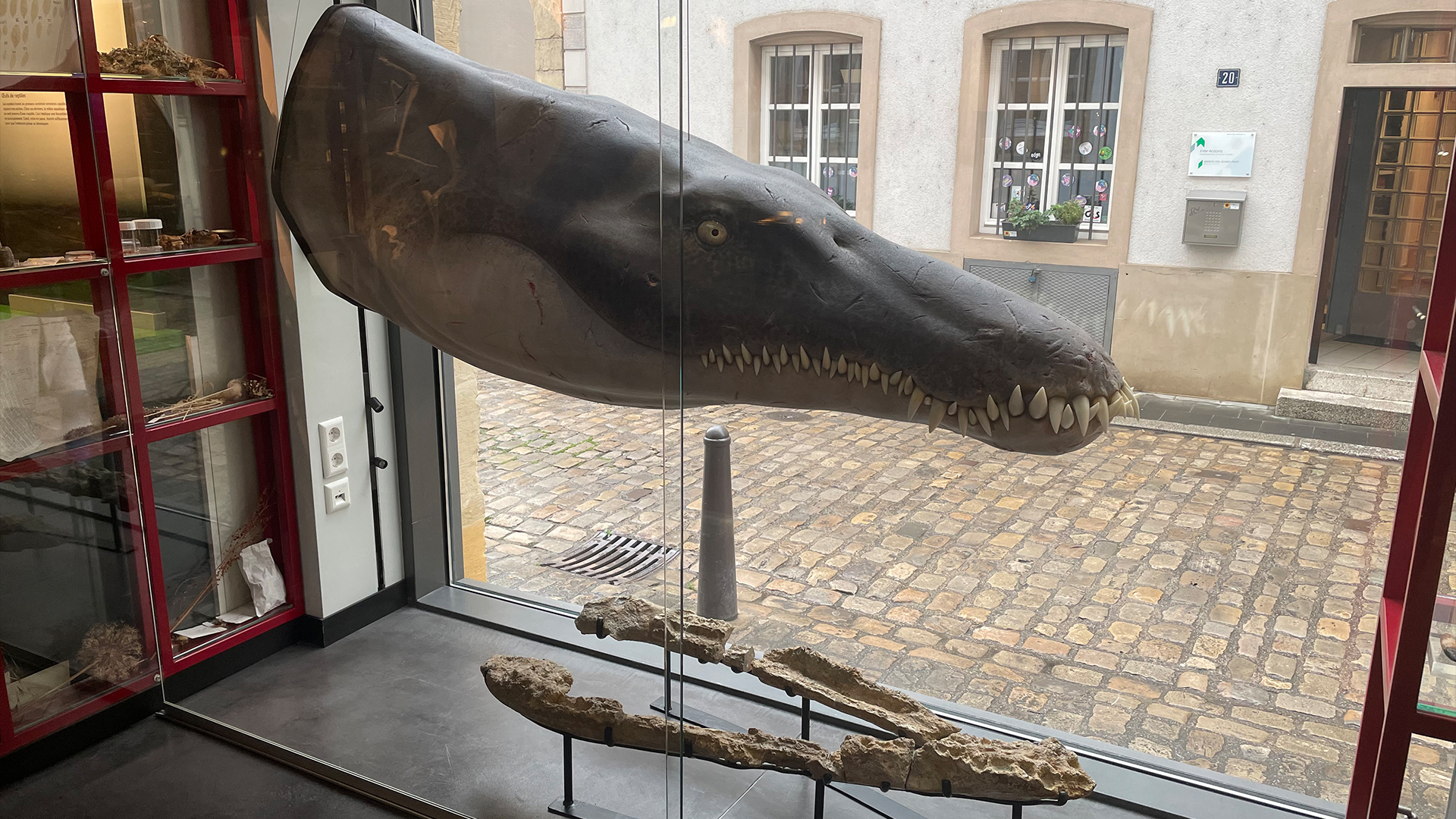

The newly described sea monster, named Lorrainosaurus, was a Jurassic (201 million to 145 million years ago) giant with a 4.3-foot-long (1.3 meters) jaw and torpedo-shaped body from the clade of pliosaurs called Thalassophonea, or "sea murderers."

Scientists first unearthed this sea monster's fossils in 1983. But in a new study, published Oct. 16 in the journal Scientific Reports, researchers re-analyzed the remains and found that the predator belonged to a previously unknown genus (group) of species and represented the oldest "megapredatory" pliosaur on record, according to a statement the authors sent to Live Science.

"Pliosaurids were the rulers of the Mesozoic seas," co-author Daniel Madzia, a paleontologist with the Institute of Paleobiology at the Polish Academy of Sciences, told Live Science. "With our animal, we are at the very beginning of a fascinating evolutionary history that we don't really understand yet."

Related: This colossal extinct whale was the heaviest animal to ever live

The fossils were unearthed in the former region of Lorraine (now part of Grand Est) in northeastern France. Paleontologist Pascal Godefroit first described them in a short 1994 study published in the journal Bulletin des Académie et Société Lorraines des Sciences. He assigned the species to a genus of pliosaurs called Simolestes, and named it S. keileni.

S. keileni received little attention after 1994, but with fossil-researching techniques becoming more sophisticated in the years since, the new study's authors decided to revisit it. They found that several characteristics separated the fossils from other known Simolestes, including broader and more "wedge-shaped" splenials — bones in the lower jaw — according to the study.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The pliosaur's mandible was also at least 1 foot (0.36 m) longer than other Simolestes species. Pliosaurs dined on sharks, sea turtles, other plesiosaurs and more, according to the statement, so the creature would have used these massive jaws to chow down all kinds of prey.

"It ate whatever it wanted to eat," Madzia said. "It was one of the largest marine predators of its time."

The team found the specimen required its own branch on the pliosaur evolutionary tree and created the genus Lorrainosaurus — so it became Lorrainosaurus keileni. L. keileni's re-evaluation pushes back the emergence of giant predatory pliosaurs by up to around 5 million years, according to Madzia.

That's not especially long in geological timescales, but it means they were on the scene just after the Jurassic food chain shifted around 175 million to 171 million years ago, which saw the decline of other apex predators, such as dolphin-like ichthyosaurs, and the rise of pliosaurs, which Madzia described as a dynasty.

L. keileni was likely more than 20 feet (6 m) long, but some giant pliosaurs grew much larger, with one potential pliosaur from the Late Jurassic recently estimated to have been 50 feet (15 m) long.

Patrick Pester is the trending news writer at Live Science. His work has appeared on other science websites, such as BBC Science Focus and Scientific American. Patrick retrained as a journalist after spending his early career working in zoos and wildlife conservation. He was awarded the Master's Excellence Scholarship to study at Cardiff University where he completed a master's degree in international journalism. He also has a second master's degree in biodiversity, evolution and conservation in action from Middlesex University London. When he isn't writing news, Patrick investigates the sale of human remains.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus