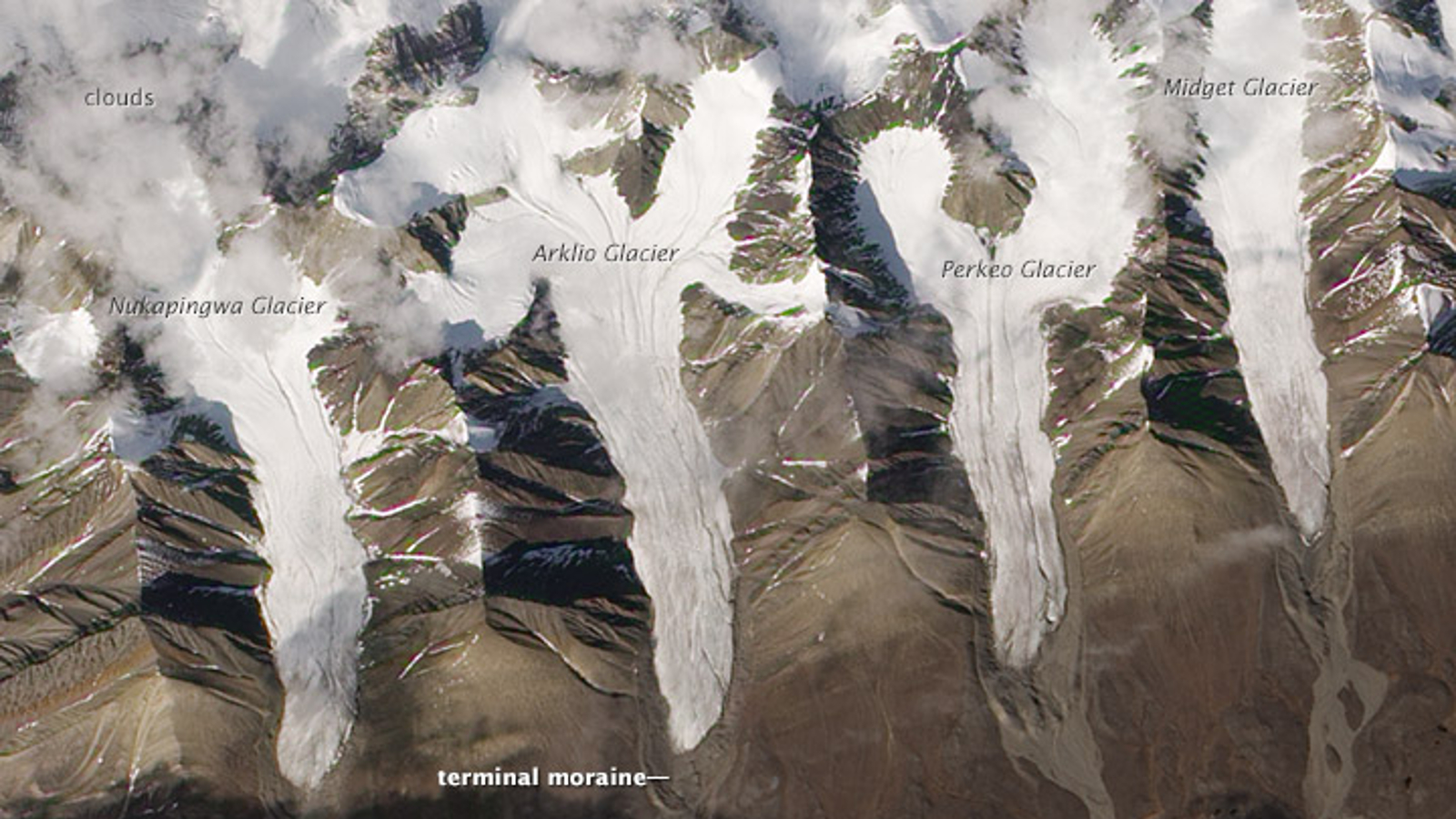

Earth from space: 4 near-identical glaciers spark new life in Arctic island's 'polar desert'

This 2012 satellite photo shows a quartet of near-identical glaciers on Canada's Ellesmere Island. The ice masses help to spark life in the otherwise barren Arctic environment.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Where is it? The Oobloyah Valley on Ellesmere Island, Canada [80.89641579, -82.79273667]

What's in the photo? The Nukapingwa, Arklio, Perkeo, and Midget glaciers

Which satellite took the photo? NASA's Earth Observing-1 (EO-1)

When was it taken? June 12, 2012

This striking satellite photo shows a quartet of near-identical glaciers perched between mountainous peaks on a barren island in the Canadian Arctic. The elongated ice masses, which are threatened by human-caused climate change, help spark new life in the surrounding "polar desert" and have provided researchers with rare opportunities to study some of the world's hardiest plant species.

The four glaciers — Nukapingwa, Arklio, Perkeo, and Midget (from left to right in the image) — are each around 2 miles (3.2 kilometers) long and around 2,000 feet (600 meters) wide on average. They are located along the northern ridge of the Oobloyah Valley at the heart of Ellesmere Island, the 10th-largest island on Earth and Canada's most northern landmass.

Ellesmere Island is a tricky place for life to thrive. Despite remaining largely ice-free all year round, temperatures range between 37.9 degrees Fahrenheit (3.3 degrees Celsius) in the summer and minus 36 F (minus 38 C) in the winter. The area also receives less than 2.5 inches (6.4 centimeters) of precipitation each year — making it a polar desert, according to NASA's Earth Observatory. As a result, only 144 people live on the island (as of 2021), despite the landmass being around the same size as the U.K..

However, seasonal meltwater from glaciers like those in the image provide areas like the Oobloyah Valley with enough moisture to sustain a sparse covering of resilient vegetation. This provides the base of a food web that supports arctic hares, muskoxen, wolves and polar bears. (The name Ellesmere means "land of muskoxen" in French.)

Related: See all the best images of Earth from space

At the terminal end of each glacier (near the bottom of the satellite image), slim crescents of rough jagged ground, known as moraines, surround the tongues of ice. Moraines are areas of churned-up earth left behind as the glaciers retreat up the valley's ridge, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. These areas are completely devoid of life when they are first freed from the glaciers' immense weight, which makes them the perfect testbed for scientists to study how arctic plants colonize new land.

In a 2013 study, researchers from Japan conducted extensive fieldwork at the moraine surrounding the Arklio glacier (second from right) and found that two plants — Dwarf fireweed (Epilobium latifolium) and a type of creeping willow (Salix arctica) — quickly colonize the space, allowing other species to eventually follow suit.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Unfortunately, human-caused climate change is causing glaciers like these to retreat much faster than normal. A 2018 study that compared satellite photos of more than 1,700 glaciers on Ellesmere Island, found that the ice masses had collectively lost around 6% of their total ice between 1999 and 2015.

While retreating glaciers could provide more space for plants to grow in the short term, the loss of ice will eventually reduce the amount of crucial meltwater that is released into the surrounding polar desert, potentially jeopardizing the entire Ellesmere ecosystem in the long run.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus