Penguins shoot 'poop bombs' more than 4 feet, incredibly important study finds

Adorable penguins are champs at projectile pooping

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

If the Olympics awarded medals for long-distance pooping, penguins would take home the gold.

These tubby, aquatic birds can squirt arcing jets of poop to distances nearly twice their own body length, and scientists recently calculated just how much force their tiny rectums produce in order to do so — and how far the poop can fly.

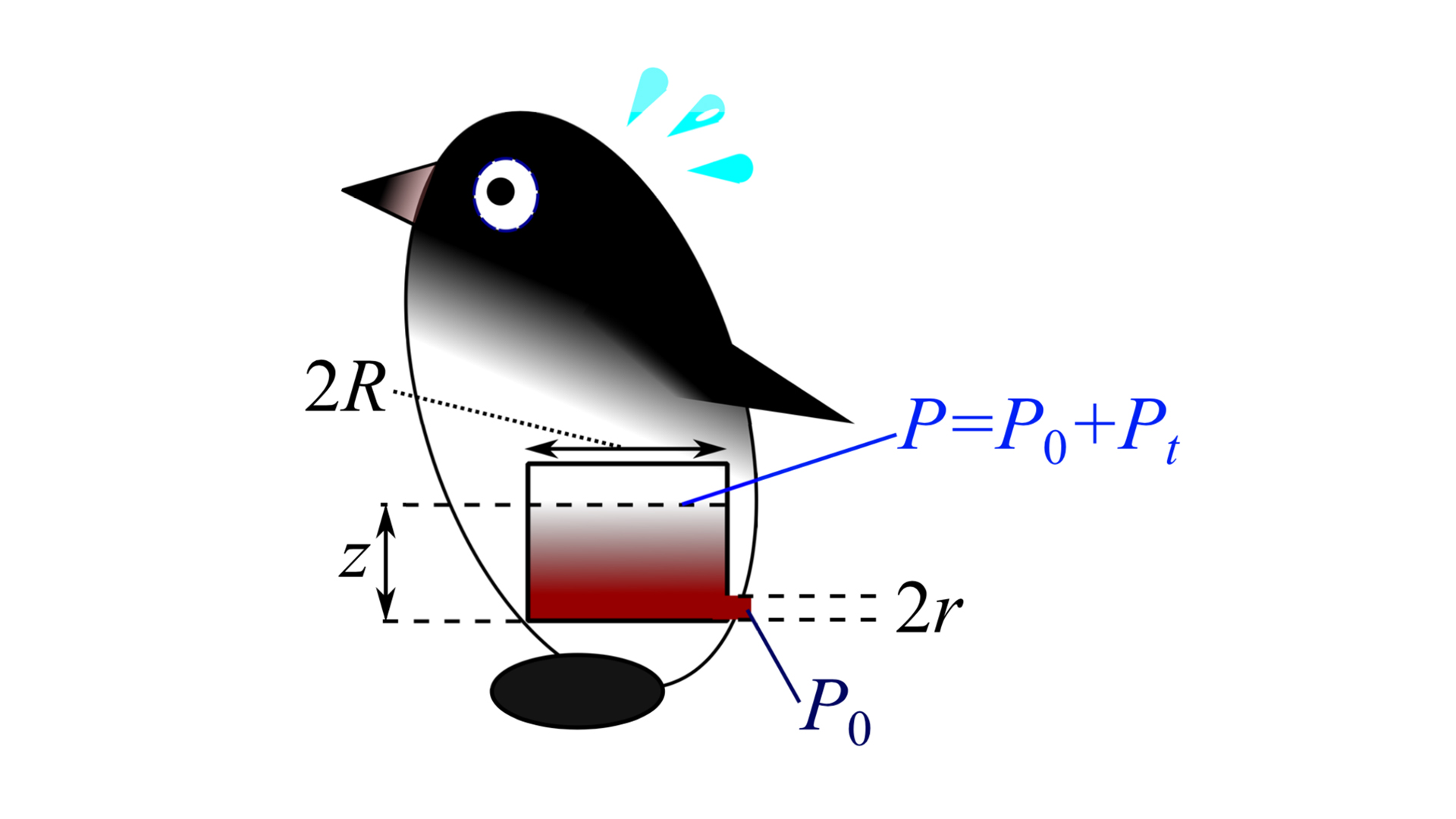

Over a decade ago, scientists had explored the pressure needed for chinstrap and Adelie penguins to expel poop along a mostly horizontal path, which they identified as penguins' most common poop direction. For a new study, which appeared on the preprint site arXiv on July 2 and has not been peer-reviewed, another team of researchers analyzed a different fecal trajectory in Humboldt penguins (Spheniscus humboldti), which often poop in a descending arc away from their nests on higher ground.

Related: Photos of Flightless Birds: All 18 Penguin Species

The team of scientists who first addressed the penguin poo puzzle published their results in 2003, in the journal Polar Biology; that pioneering study won the authors an Ig Nobel Prize in 2005 for fluid dynamics.

When a new team of researchers revisited the question, they expanded on the earlier results by recalculating internal pressures inside the penguin's gut and rectum, correcting for viscosity of the poo, and factoring in air resistance along an arcing trajectory. They then discovered that the forces at work were even more extreme than previously suggested.

Pressure is measured in units called kilopascals (kPa), where 1 kPa is 1,000 newtons per square meter. In the new study, the scientists calculated that the pressure generated in the rectums of pooping penguins was as much as 28.2 kPa — about 1.4 times the estimate in the 2003 study.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"I was surprised by the extremely strong penguin's rectal pressure," said lead study author Hiroyuki Tajima, an assistant professor in the Department of Natural Science at Kochi University in Japan.

Though Humboldt penguins stand only 28 inches (71 centimeters) tall, the scientists discovered that the birds can generate enough poo-propelling energy to send fecal "bombs" flying at speeds of nearly 5 mph (8 km/h), landing up to 53 inches (134 cm) away. This achievement would be comparable to an adult human shooting their feces to a distance of more than 10 feet (3 meters), Tajima told Live Science in an email.

Victor Benno Meyer-Rochow, lead author of the 2003 study, declared that he was "very pleased that other researchers have taken up our ideas to look into penguin pooping," according to Improbable Research, the humorous science organization that awarded Benno Meyer-Rochow the 2005 Ig Nobel Prize.

The new study described the penguins expelling a fecal arc that curved upward before descending, which Benno Meyer-Rochow and his colleague had not seen in Adélie penguins. Nevertheless, "it is of course possible that either we missed that or that these penguins sometimes do that when they stand on an uneven rock and/or bend forward more than what we had observed," Benno Meyer-Rochow told Improbable Research.

Birds that eat meat or fish typically poop with more force than seed-eaters, likely because their waste contains higher amounts of irritating uric acid, Benno Meyer-Rochow wrote in a 2019 blog post.

While blasting poop jets helps penguins keep their nests tidy, their high-pressure pooping poses an occupational hazard for penguin caregivers in zoos and aquariums, the study authors reported. Their findings therefore have a practical side: helping wildlife experts who care for penguins to establish a foolproof "safety zone," so they can keep well out of range during the birds' explosive bathroom breaks, Tajima said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus