Ötzi the Iceman may have scaled ice-free Alps

During or just before the life of the Copper Age wanderer, many high peaks in the Alps were ice-free.

Ötzi the Iceman, a Copper Age wanderer found mummified in the Alps nearly three decades ago, may have lived at a time when the glaciers were advancing down from the highest peaks to the lower slopes of the mountains.

The ice that preserved Ötzi upon his death in about 3300 B.C. has melted since the mummy was discovered in 1991. But a new analysis of ice only 7.4 miles (12 kilometers) from where Ötzi was found suggests that only the very highest peaks were covered in glaciers until slightly before the iceman's lifetime. Just a few hundred years before Ötzi was born, nearby mountains may have been ice-free.

The findings suggest that during the Holocene, the epoch covering 11,650 years ago to the present, glaciers in the Alps have changed dramatically.

Related: Mummy melodrama: Top 9 secrets of Ötzi the iceman

"Our main finding is that the ice is 5,900 years old, more or less, which is just a bit older than the iceman," said Pascal Bohleber, who studies glacial ice at the Austrian Academy of Sciences. "This suggests that, in this region, we had a time where glaciers started to form in conditions that were ice-free or with glaciers distinctly smaller than today."

A history in ice

Most of the history of ice in the Alps has been gleaned from glacial tongues within relatively low-elevation valleys, Bohleber told Live Science. Ice cores have been drilled at a few summit locations, he said, but most of those are in the western Alps above about 12,000 feet (4,000 meters).

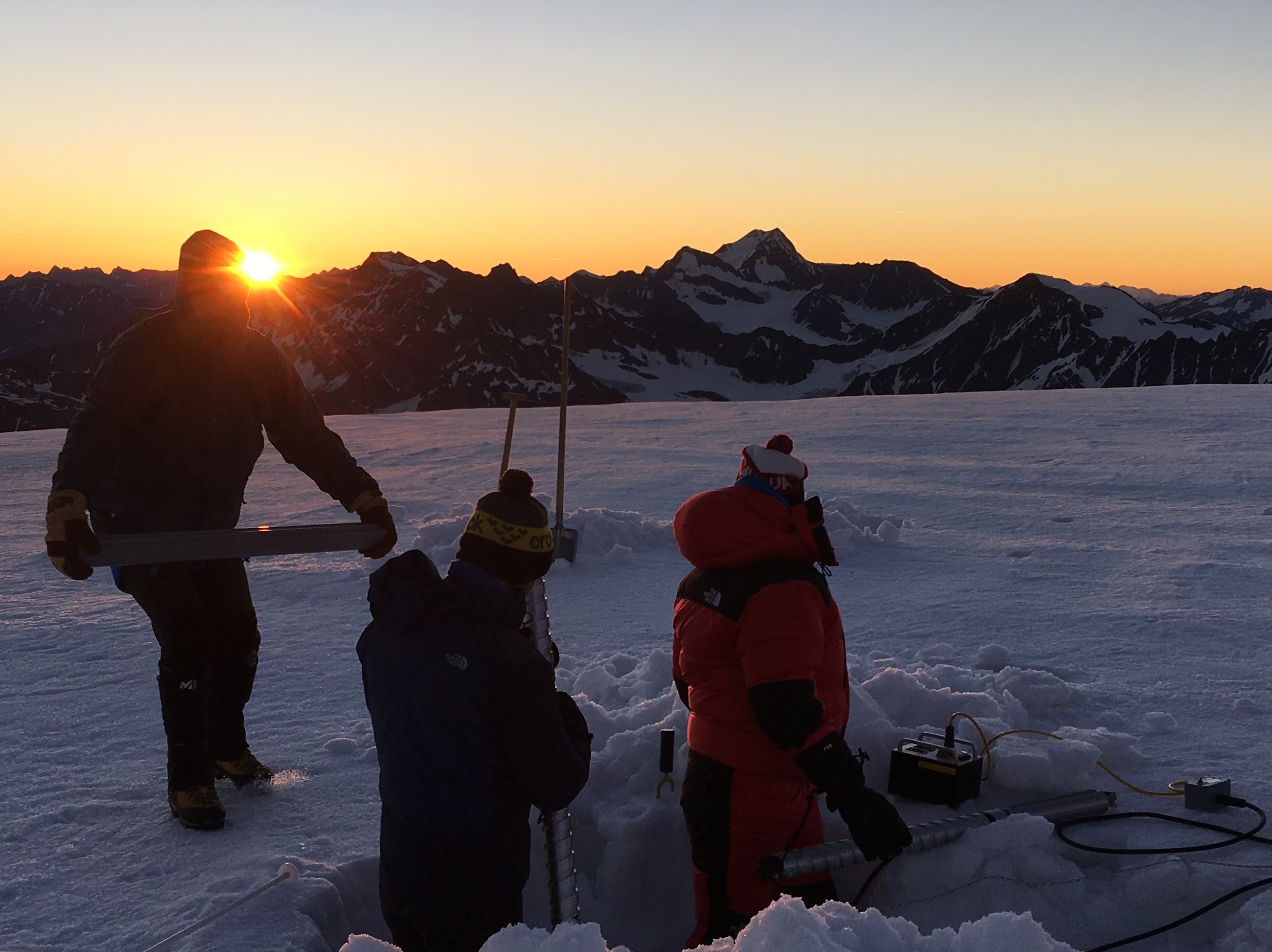

The two ice cores analyzed in the new study came from the summit glacier of Weißseespitze in the Austrian part of the Ötzal Alps, at about 11,500 feet (3,500 m) elevation. Bohleber and his colleagues ferried themselves and their equipment to the summit by helicopter and drilled 36 feet (11 m) down to where the ice was frozen fast to the bedrock. This was crucial for a continuous record of ice, because meltwater not only carries away the historical record as it flows but causes the ice to slide and deform, also erasing decades or centuries of data. Fortunately, the ice at the base of the Weißseespitze glacier had never melted, but warming temperatures still caused the researchers trouble. Meltwater on top of the ice threatened to contaminate layers below, so the team did much of their drilling after sunset, when the ice was firmer.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The research team then analyzed microscopic amounts of carbon trapped within the ice. The method used radiocarbon dating, which measures the level of carbon 14 in a sample. Carbon 14 is a radioactive variation of carbon that decays over time, thus providing a sort of clock that pinpoints the age of the sample.

The results showed that the oldest ice dated back to 5,900 years ago, give or take 700 years, the researchers report today (Dec. 17) in the journal Scientific Reports. (Ötzi died approximately 5,300 years ago.)

This is younger than ice found at higher elevations elsewhere in the Alps, particularly above 13,100 feet (4,000) meters. At Colle Gnifetti glacier in the Swiss-Italian Alps, for example, the oldest ice dates back at least 11,500 years.

Past ice, future melt

Alongside data from stalagmites and ancient forests, the ice record seems to suggest that during the Holocene, climate variations dramatically changed glacier extents even at high elevations, Bohleber said, and it's possible that Ötzi watched the glaciers advance during his 45-year life span. That could have implications for current studies of climate change, he added.

"We are now adding a strong anthropogenic [human-influenced] component in climate change on top of this, and see the glaciers disappearing so rapidly today," Bohleber said. "This rate of change is something that we urgently need more information on."

Unfortunately, the research can't directly answer one enduring mystery about Ötzi: whether he died in an ice field or the ice entombed him soon after. The ice around the mummy melted before scientists had the technology to date minuscule amounts of carbon as they can today, so there's no way to investigate the question directly. It's not clear whether the glaciers had advanced to where the iceman died, but the new results do show that it was icy a short hike away.

The lost opportunity to study Ötzi's resting place highlights the myriad other opportunities that could be lost within just a few years. The Weißseespitze glacier is expected to vanish within two decades. The scientific information held within many Alpine glaciers could be gone even sooner than the ice itself, as meltwater will disturb, and ultimately erase, the potential climate record in the ice layers, Bohleber said.

"If we don't do it now, we will have little time to do this in the future," he said, "so we are really searching for other sites that may still have this old ice."

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus