Oldest animal life on Earth possibly discovered. And it’s related to your bath sponge.

The fossils are more than 350 million years older than the next-oldest sponge fossils.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

That sea sponge hanging in your shower may be able to trace its evolutionary lineage to nearly a billion years ago, according to fossils that could be the oldest examples of animal life on Earth.

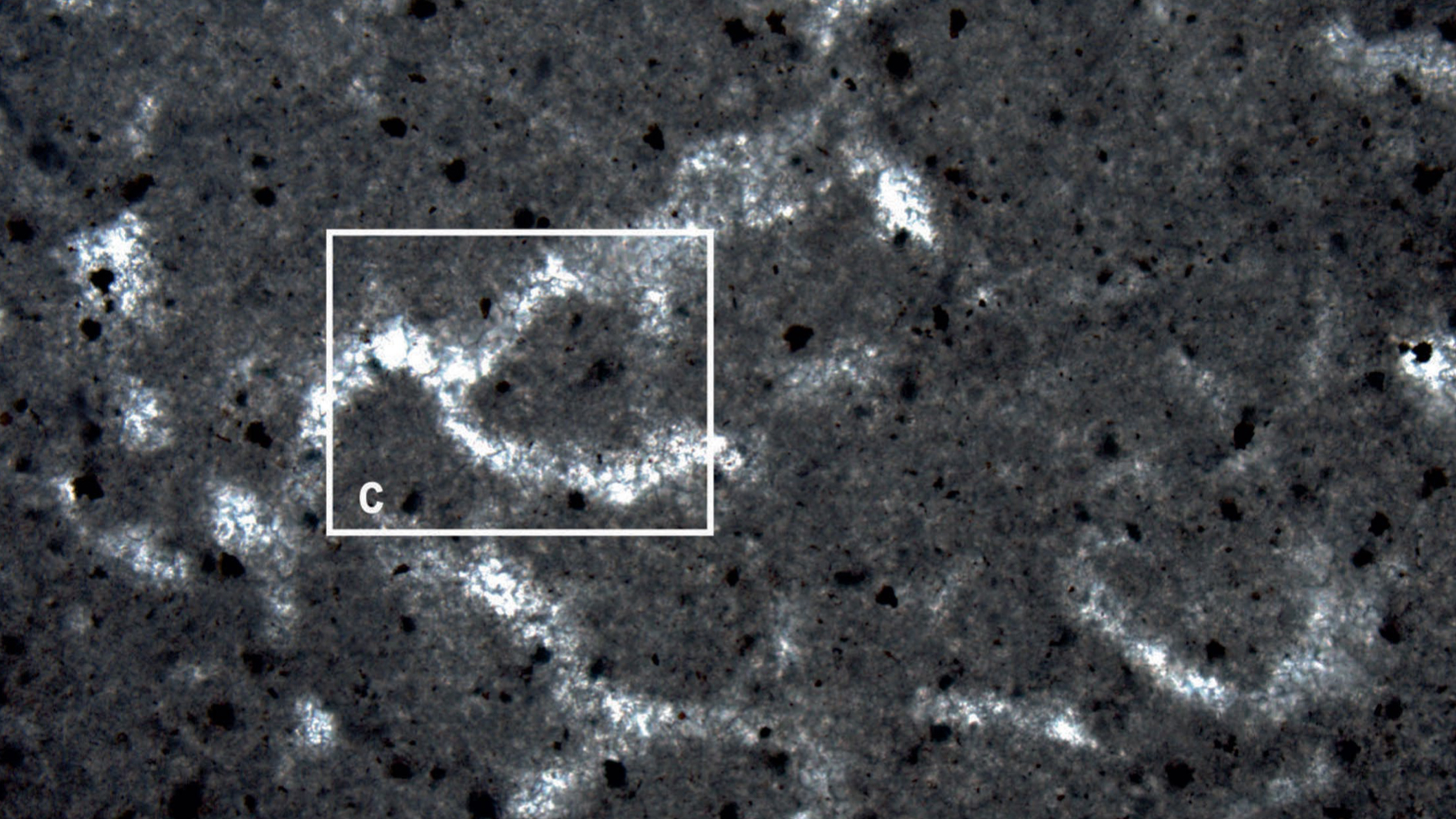

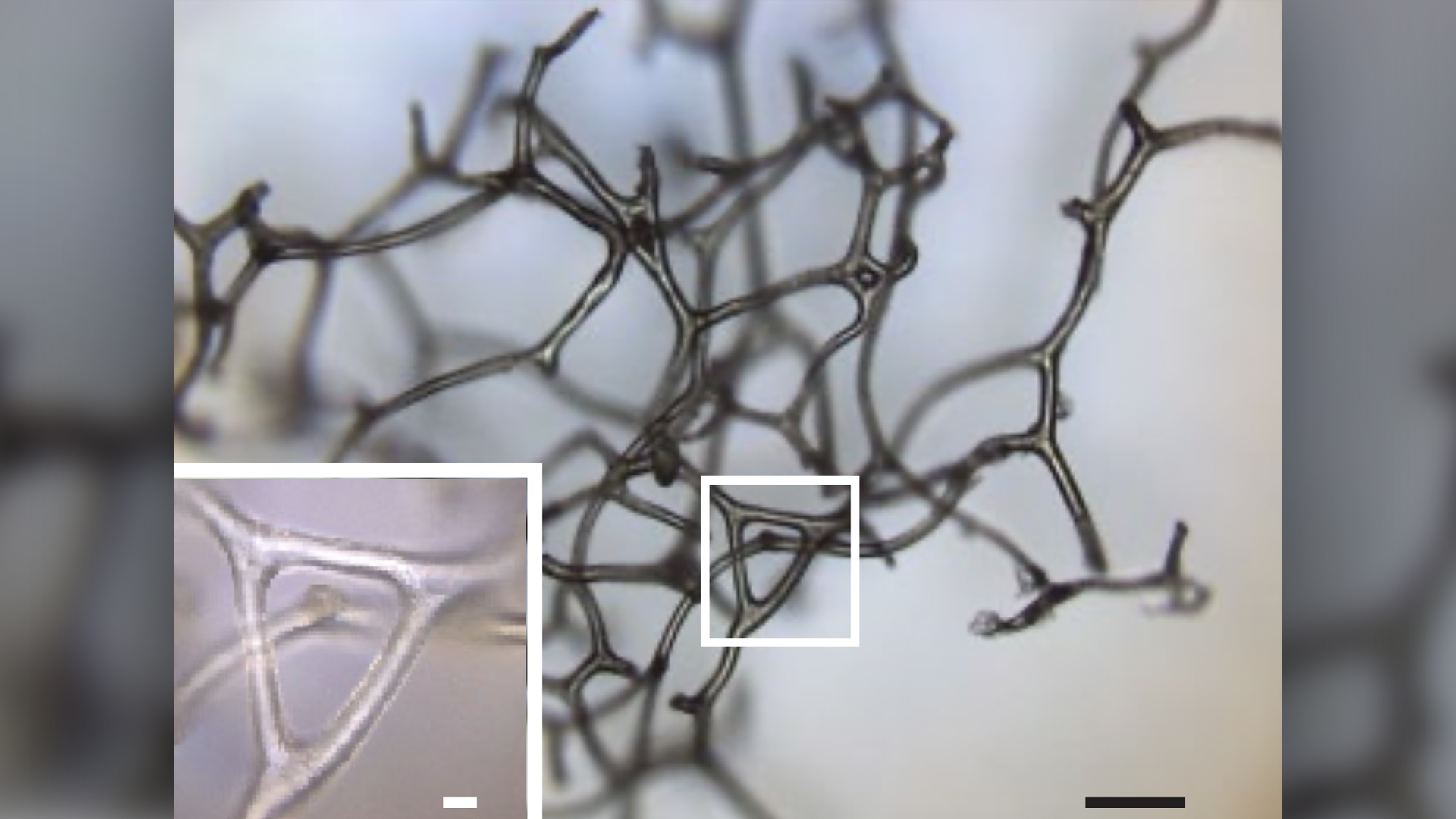

The 890-million-year-old fossils of what may be ancient sponges were found in Canada's Northwest Territories, and their tiny and delicately branching tendrils are invisible to the naked eye. But under a microscope, the preserved organic tissue revealed a mesh-like structure that was strikingly similar to that of skeleton fibers in modern bath sponges, which are part of a soft-bodied-sponge group known as keratose demosponges, or horny sponges.

Paleontologists already consider sponges to be good candidates for the earliest form of animal life. If this analysis is correct and the Canadian fossils truly represent ancient sponges, they would predate the oldest known sponge fossils by about 350 million years, according to a new study.

Related: In images: The oldest fossils on Earth

Author Elizabeth Turner, a professor of carbonate sedimentology and invertebrate paleontology at Laurentian University in Ontario, Canada, first noticed the bizarre fossils in the early 1990s, while examining samples of massive fossil reefs that were built by ancient cyanobacteria, she told Live Science.

When she peered through a microscope at thin slices of the rocks, she saw something in a handful of samples "that was a lot more complicated than cyanobacteria," Turner said. "I thought it looked a bit like some sponge fossils from younger rocks."

But sponges weren't her research focus at the time, so she temporarily shelved the peculiar fossils until years later, when she returned to the region to collect additional samples. By then, other scientists had published descriptions of fossilized sponge skeletons that strengthened Turner's suspicions about her unusual discoveries.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"If you look at the body of a fossil sponge microscopically, it has this characteristic microstructure, which was described and characterized and fully affiliated with the spongin [a type of collagen protein] skeleton in modern keratose demosponges," Turner said. "And it's the identical structure to what I have." She described the fossils in a study published July 28 in the journal Nature.

Finding the sponge fossils in a fossilized cyanobacteria reef made sense, because such reefs would have produced lots of oxygen. Even if sponges couldn't compete with the cyanobacteria for a spot on the seafloor, they would have likely settled in parts of the reef where they could reap the benefits of the "oxygen factory," Turner explained. Cyanobacteria could also have provided food for sponges, nourishing them with polysaccharides shed from their cell walls and suffusing the water around the reef with nutritious "suspended snot."

"There are lots of good reasons why a sponge might have lived in the exact environment where I found these putative fossil sponges," Turner said.

Related: 7 theories on the origin of life

The fossils' branching tendrils do somewhat resemble those of ancient fungi, which can be seen in fossils that were described earlier this year and represent the oldest evidence of land fungus, dating to 635 million years ago, Live Science reported in January. But Turner ruled out a fungal identity for the newfound fossils, as the fibers in sponges — both in fossils and modern sponges — branch and rejoin in a three-dimensional network. This makes them visibly different from fungal branches, which join up to each other at right angles, Turner explained.

"What she has found is very specific for this type of keratose sponges," Joachim Reitner, a professor in the Center for Geosciences at Georg-August-University in Göttingen, Germany, told Live Science.

"This material, what we call spongin, that's a complex protein compound; it's very resistant against microbial degradation," said Reitner, who reviewed the study for Nature. "That's why we have these spongin fiber networks in the fossil record. That type of network is characteristic of sponges — you can classify the type of sponges on the basis of the spongin network. No other organisms make that," he said.

Earliest animals

When did animal life first appear on Earth? Prior to around 580 million years ago, there's very little physical evidence of animals — but that doesn't mean they didn't exist, as soft-bodied animals usually don't fossilize well.

Preserved molecules, or biomarkers, that are thought to be unique to animals are one source of clues about ancient animal life. In 2018, traces of cholesterol in a fossil dating to 558 million years ago enabled researchers to identify a bizarre soft-bodied creature called Dickinsonia as an animal, Live Science reported that year.

And more than a decade ago, scientists detected fossilized traces of what appeared to be a fat compound, or sterol, from ancient sponges dating to 635 million years ago, seemingly representing the oldest known example of animals. However, in two studies that were published in 2020, researchers revisited that claim, finding that the sterols described in 2009 were likely produced by decaying algae, not by animals, Live Science previously reported.

"An important find"

When physical fossils are scarce, scientists studying Earth's evolutionary past often turn to the molecular clock, David Bottjer, a professor of Earth sciences at the University of Southern California, Dornsife, told Live Science.

By evaluating differences in the DNA of modern organisms, alongside rates of mutation, the molecular clock method can give an estimate of when animals in a given group may have first evolved, said Bottjer, who was not involved in the new study. According to this approach, organisms are thought to have appeared at a more ancient date than is represented by the fossil record, and the new findings support that conclusion, Turner wrote in the study.

"If I'm correct in my interpretations of this material, animals emerged long before the appearance of traditional animal fossils — they had a long prehistory," Turner said.

The oldest "incontrovertible" sponge fossils are mineralized spicules — pointy structures found in many types of sponges. In April, another team of researchers described spicule fossils that were around 535 million years old — dating to just before the Cambrian period (543 million to 490 million years ago) — in the Journal of the Geological Society. But the molecular clock method has long suggested that sponges are much older than that, and Turner's study provides the first physical evidence of how truly ancient sponges might be. Though spicules are the most common fossil markers for sponges, many modern sponges don't have spicules, and the discovery of what is possibly an 890-million-year-old sponge that shares that trait is "an important find," Bottjer said.

"It's a great example of pre-Cambrian paleobiology looking for things in a different way," he added. "I think it's a high-quality study, and it deserves to be treated very seriously."

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus