This man can't see numbers. But his brain can.

He can see "0" and "1," but other numbers look to him like a bowl of spaghetti.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

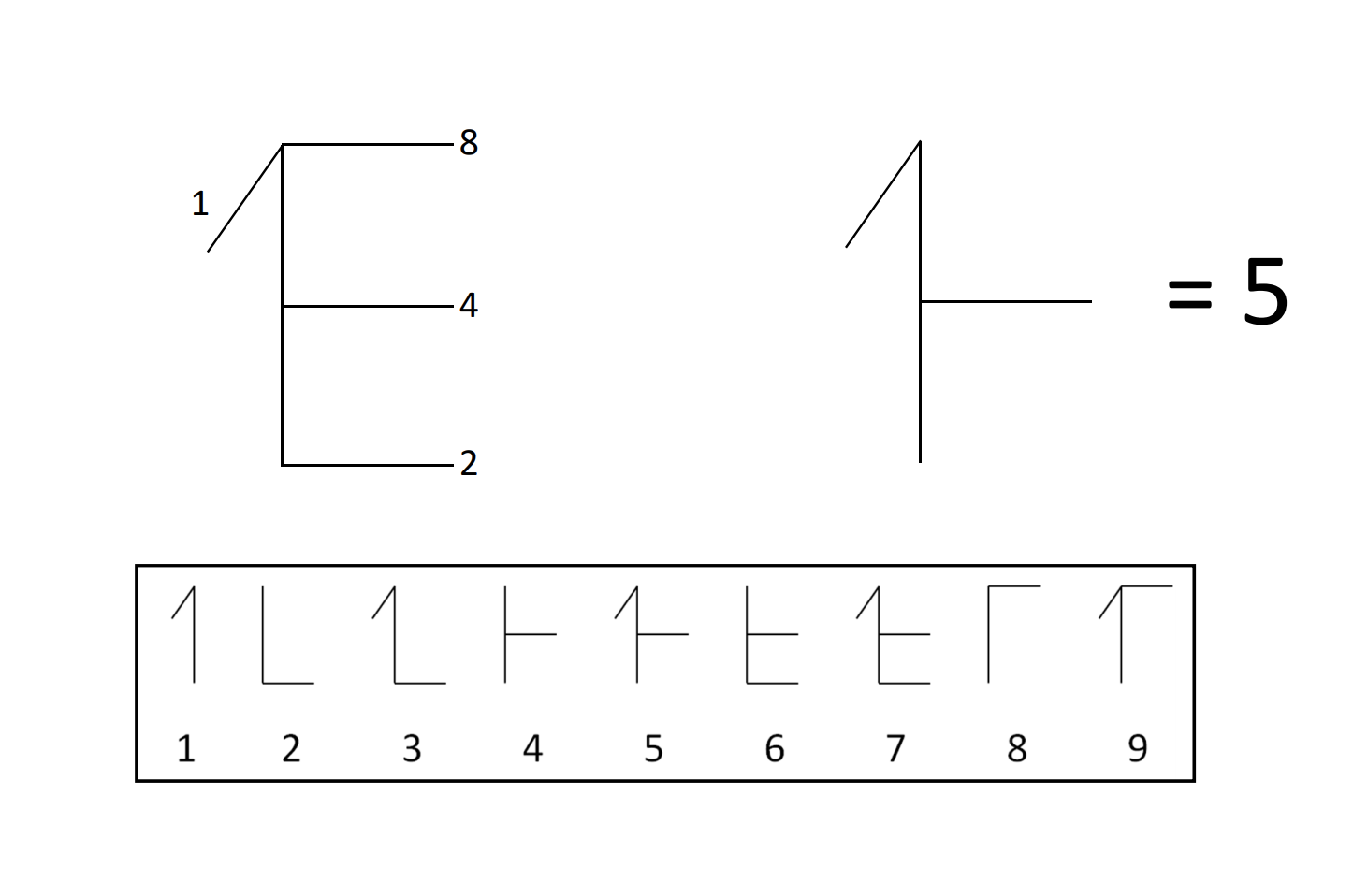

A man held up a big foam number "8" on its side like an infinity sign and said the object, with its two loops, looked like a mask to him. But when he turned the foam number upright, the object dematerialized into a jumble of lines.

"He described it as being the strangest thing he's ever seen," said David Rothlein, a postdoctoral researcher and cognitive scientist at the Veterans Affairs Boston Healthcare System. This man, referred to by his initials RFS, has a rare degenerative brain condition that does not allow him to "see" numbers — on paper, as objects or even those secretly embedded in scenes.

There are exceptions: While the numbers 2 through 9 look like a scramble of meaningless curves to him, he has no problem seeing the number "0" and the number "1," according to a new case report on which Rothlein is a co-author. RFS' case is more evidence that even in healthy brains, we aren't always aware of what we see.

Related: Inside the brain: A photo journey through time

In 2010, RFS suffered from a sudden event in which he developed a headache, trouble with understanding and expressing speech, amnesia and temporary vision loss. A couple of months later, he started having difficulty walking, involuntary muscle spasms and a tremor — and his motor symptoms worsened as the years went on.

He was diagnosed with a rare degenerative brain disorder called corticobasal syndrome, which leads to problems in movement and language. His brain scans have revealed widespread damage and volume loss in the cerebral, midbrain and cerebellar regions of the brain, according to the study.

His problem with seeing numbers happened very subtly over a couple of weeks, said senior author Michael McCloskey, a professor of cognitive science at Johns Hopkins University.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A bowl of spaghetti

RFS was a patient at Johns Hopkins Hospital and was referred to McCloskey by one of his colleagues. McCloskey's team began studying RFS in 2011, when the man was 60 years old.

To the researchers' knowledge, RFS is the first patient with an inability to see numbers. "He sees something … a scramble of lines and he calls it spaghetti," McCloskey said. RFS knows that what he's seeing is a number — though he doesn't know which number — just because he doesn't see this series of nonsense lines for anything else.

And he can't memorize the different orientations of lines and assign a number to them, because they change every time he looks away and looks back, McCloskey said. "What is most striking though is that it affects the numbers and not other symbols," he told Live Science. Symbols or letters may look similar to numbers; a capital B, for example, looks like an 8. But he has no problem seeing letters or other characters.

Related: The 27 most interesting medical case reports

This means that his brain has to determine that these digits he's looking at are in their own special category (aka they are numbers) in order for his comprehension of them to be scrambled, McCloskey said. But the question then is: If he can't see them, how does he do that?

It's also "surprising" that his brain doesn't have problems with "0" and "1," McCloskey added. It's not clear why, but those two numbers might look similar to letters like "O" or "lowercase l," he said. Or those two numbers might be processed differently than other numbers in the brain, as "zero wasn't invented for quite a long time after the other digits were," he said.

To study what is happening in RFS' brain, the group conducted a number of experiments. They embedded an image of a face into a number to see if RFS would see the face normally, or scrambled like he saw the number. They also hooked him up to an electroencephalography (EEG) to measure the electrical activity in his brain. RFS said he did not see the face at all — he didn't even know anything was there aside from a digit, since he was seeing the jumbled mess. But while he was peering at this face-in-a-number, according to the EEG, he was showing the same brain response as when he was shown a face (with no number) that he reported seeing embedded in a letter.

Similarly, the researchers conducted a word test in which they had RFS press a button every time he saw a particular word, such as "tuba." When the researchers embedded that word in a number, he didn't see the word and wouldn't press the button.

Yet his brain activity was the same regardless of whether the target word was alone or inside of a digit. That suggests that his brain does all of the complex processing and knows he's viewing the word and what word it is — but that knowledge never comes up in his awareness, Rothlein said.

So it seems "you can do an awful lot of work in the brain to know what it is you're looking at without any awareness resulting from that," McCloskey said.

What we don't see

The processing of numbers "is happening very normally," in RFS' brain, McCloskey said. When you're looking at stuff, that signal comes in from the eyes but then the brain does a lot of work to figure out what that shape is and how it's separate from other things you're simultaneously looking at. RFS' brain knows that he's looking at the number 8, for instance, but doesn't let him become aware of that knowledge.

"We think RFS' brain is just like everybody else's except that his disease has damaged ... something … that has to happen for awareness," McCloskey said. "He does the brain work to determine what he's looking at, but then the additional work to be aware of it is going wrong."

Once the brain has determined what you're looking at, one of two things may cause awareness, and it's an ongoing debate in the field of neuroscience, he said. The brain might either send signals to an area involved in higher-processing tasks such as analyzing and identifying what you're looking it or it may send signals back down to areas of the brain involved in lower-processing functions where just the basics of the figure, such as its shape, is analyzed, McCloskey said. "Whichever of these it is, that's where things are going wrong with RFS," McCloskey said.

"I can't say that I've seen this in any of my corticobasal patients," said Dr. Timothy Rottman, a senior clinical research associate at the University of Cambridge and Honorary Neurology Consultant at Cambridge University's Addenbrooke's hospital, who was not a part of the study. Though based on the description of his disease, "I would have thought it closer to … [a] variant of Alzheimer's disease" rather than corticobasal syndrome, two conditions that are difficult to distinguish, he said.

Semantic memory is a set of ideas and concepts that we don't draw from personal experience, but are rather common knowledge such as the sound of letters. So it's likely that RFS' inability to see numbers may stem from trouble integrating language and vision, "possibly tapping into some accessing of semantic knowledge," Rottman told Live Science in an email. "They've done a good job in finding a very specific deficit," and their interpretations of this integration are "very reasonable," he added.

Because RFS' condition affected most of his brain, the researchers aren't able to pinpoint where in the brain things go awry. The team was able to study RFS for several years before his physical illness made it difficult to go any further. Physically, his condition has worsened but "mentally, he's still the same as he was except for he can't see the digits," McCloskey said.

The researchers created a new set of numbers for him to work with, which he could see fine. This scrambling likely "only happens for digits in their usual form because recognizing those digits involves different brain areas than recognizing numbers in different forms," such as words or surrogate digits, McCloskey said.

RFS was an engineer and worked as an engineer for several years after this problem with digits arose, Rothlein said. "He is perfectly capable at number processing, so if you asked him to do arithmetic using number words or even Roman numerals he can do math just fine," he said. "In fact, he's quite good at math."

The findings were published today (June 22) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

- History's 17 most bizarre amnesia cases

- 9 surprising risk factors for dementia

- 3D Images: Exploring the human brain

Originally published on Live Science.

OFFER: Save 45% on 'How It Works' 'All About Space' and 'All About History'!

For a limited time, you can take out a digital subscription to any of our best-selling science magazines for just $2.38 per month, or 45% off the standard price for the first three months.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus