Glowing embryonic gecko hand and otherworldly slime mold amaze in winning microscope photos

A psychedelic dinosaur bone is also featured in Nikon's Small World Photomicrography Competition 2022.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Shots of a stunningly detailed embryonic gecko hand, an otherworldly slime mold and a psychedelically stained segment of dinosaur bone are among some of the intricate and awe-inspiring entries in a recent microscopic photography contest.

The Nikon Small World Photomicrography Competition, which has been running for almost 50 years, is a specialist event that blends "science and artistry under the microscope," organizers said in a statement. The contest, which highlights the beauty of incredibly small things, is open to anyone as long as the images are captured using a light microscope. This year's top 20 images were revealed by event organizers on Oct. 11.

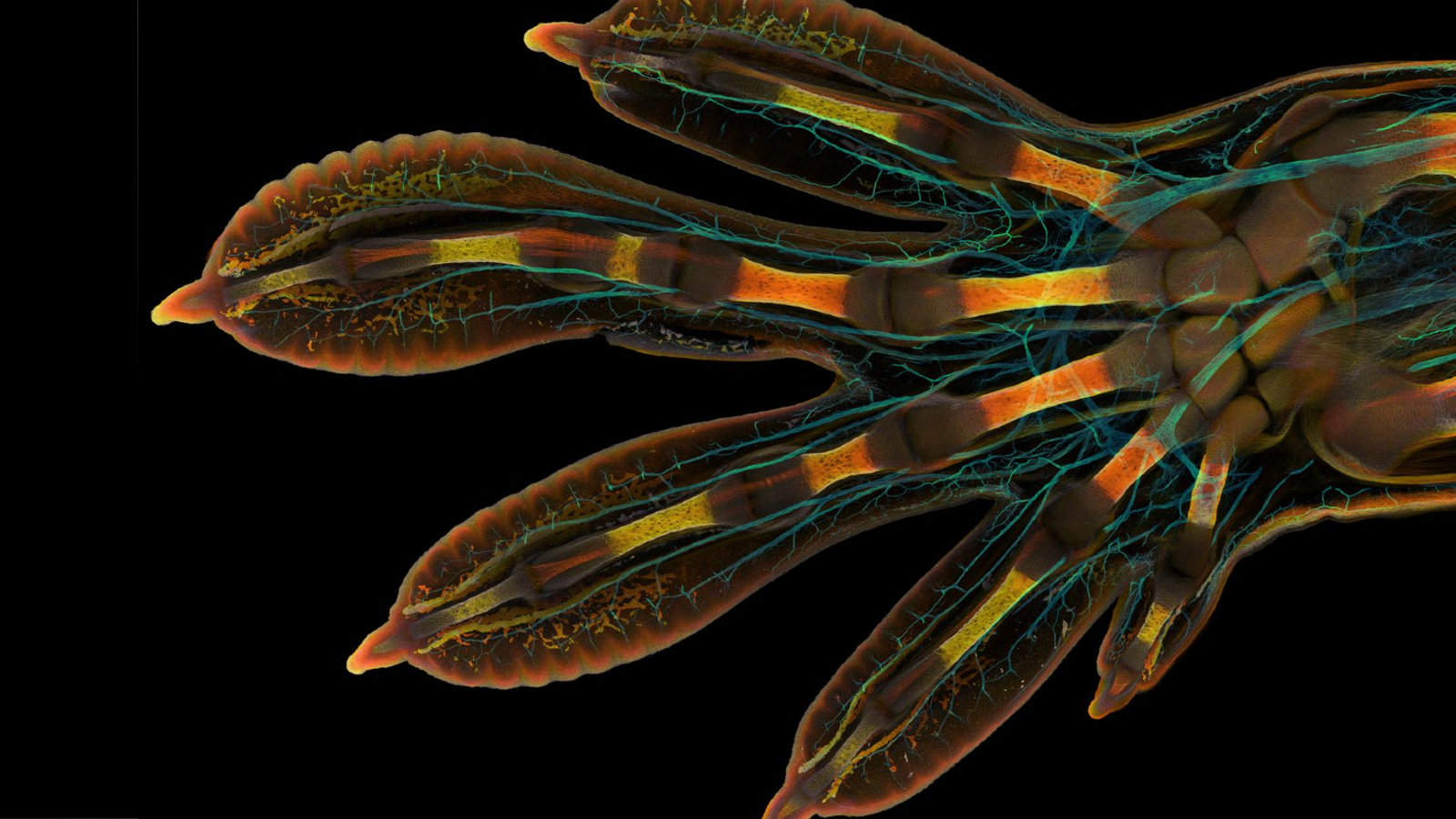

Grigorii Timin, a doctoral student at the University of Geneva in Switzerland, won first prize at this year's competition with a painstakingly curated shot of a developing gecko hand stained with fluorescent dyes. Captured under the supervision of Michel Milinkovitch, an evolutionary geneticist at the University of Geneva, the winning picture is a composite of thousands of individual images that have been stitched together.

"The scan consists of 300 tiles, each containing about 250 optical sections, resulting in more than two days of acquisition and approximately 200 GB of data," Timin said in the statement. The developing lizard's hand is around 0.12 inch (3 millimeters) long, which is a massive subject to capture with microscopic detail, he added.

Related: Hidden secrets revealed in microscopic images of ancient artifacts

Researchers stained the gecko's nerves with a cyan-tinted dye and colored the reptile's bones, tendons, ligaments, skin and blood cells in warmer colors like yellow and orange. Zooming in on particular regions of the image reveals how "structures [within the hand] are organized at a cellular level," Timin said.

However, the multi-colored gecko hand was not the only image that stole the show at this year's competition.

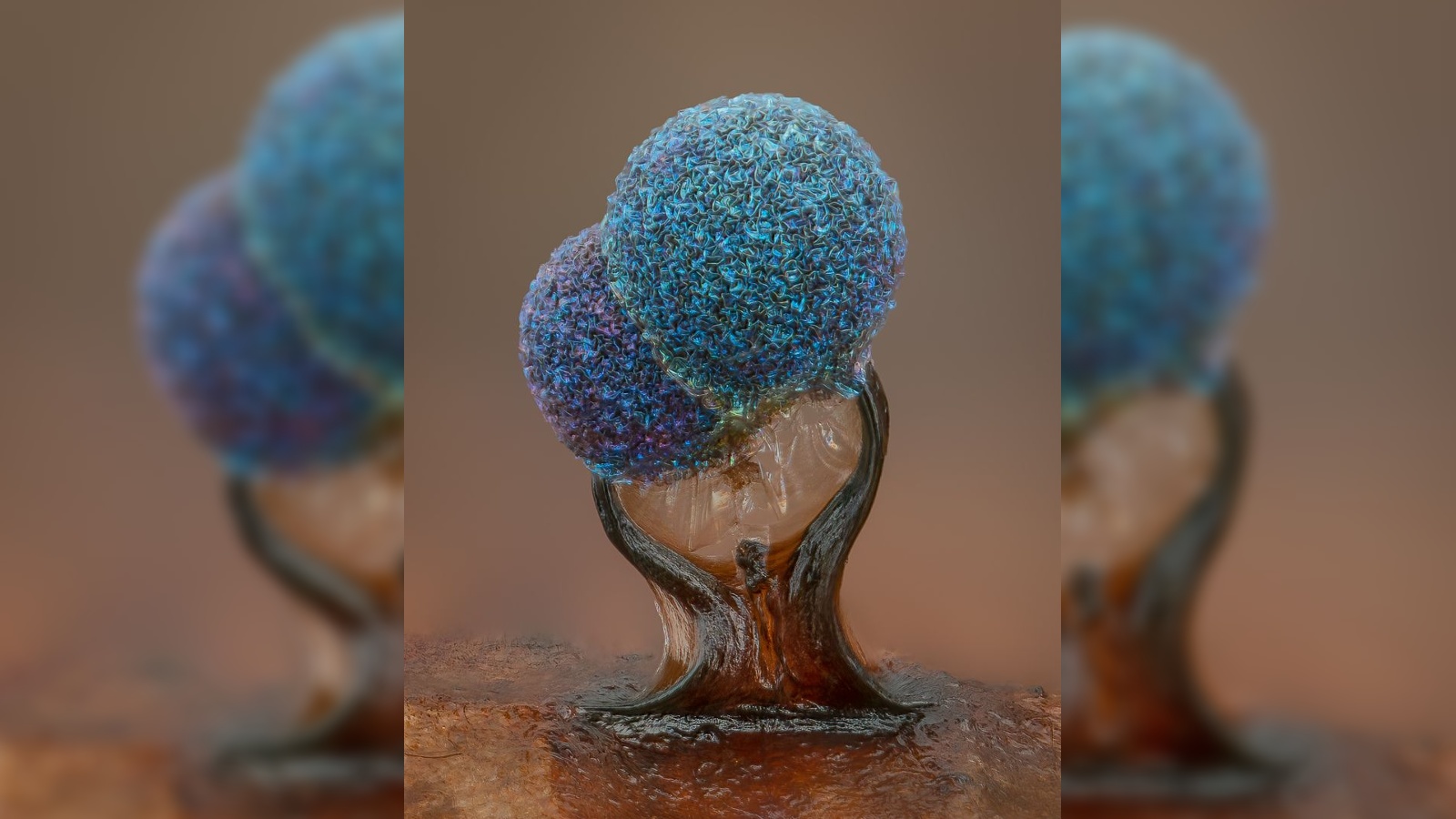

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Alison Pollack, a California-based photographer who specializes in macro and extreme macro photography, won 5th place with a stunning shot of a slime mold from the genus Lamproderma. The iridescent blue structure, which looks like some sort of alien tree, is the organism's reproductive fruiting body. However, like all slime molds, the strange specimen is one individual cell with no internal membranes and multiple nucleuses dotted throughout its body. The image is also a composite, this time of more than 100 images stitched together.

"Despite the rather unflattering common name, slime molds are astonishingly beautiful organisms," Pollack told Live Science in an email. "While they grow in almost any kind of environment all over the world, they are little known because they are so tiny."

This particular slime mold was collected by Pollack from a leaf just outside her home after heavy rainfall. The best place to look for slime molds is in woodland areas after it has rained, Pollock said. Anyone can go hunting for the bizarre creatures, but "unless you have very good eyes, they are best found with the aid of a light and a good magnifying lens," she added.

Randy Fullbright, a photographer based near the Dinosaur National Monument in Utah, took 13th place with a boldly colored shot of a dinosaur bone fragment stained yellow and blue. The bone likely belonged to a sauropod — a group of large dinosaurs with long tails and necks, such as Brachiosaurus and Diplodocus— and was uncovered at a ranch at the Morrison Formation in northwest Colorado, which dates back to around 150 million years ago toward the end of the Jurassic period, Fullbright told Live Science in an email. The specimen was cut using a diamond saw, and the minerals within the bone were stained different colors, he added.

"I feel very blessed for the opportunity to show a world that most will never see," Fullbright said.

Tenth place in the competition went to Murat Öztürk, a Turkish photographer based in Ankara, with a breathtaking shot of a fly trapped under the chin of a tiger beetle. The fly appears to be struggling to escape the beetle's death grip — the beetle is sticking its mandibles, or serrated mouthparts, into its prey's eyes.

Tiger beetles, which are a subfamily of ground beetles known as Cicindelinae, are the fastest-running insects on Earth. The fastest tiger beetle species, Rivacindela hudsoni, can run at around 5.6 mph (9km/h), which is around 120 times its own body length per second. In 2014, a study published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B, showed that, at this speed, R. hudsoni becomes functionally blind while running and relies on its antennae to see its prey instead of using its eyes.

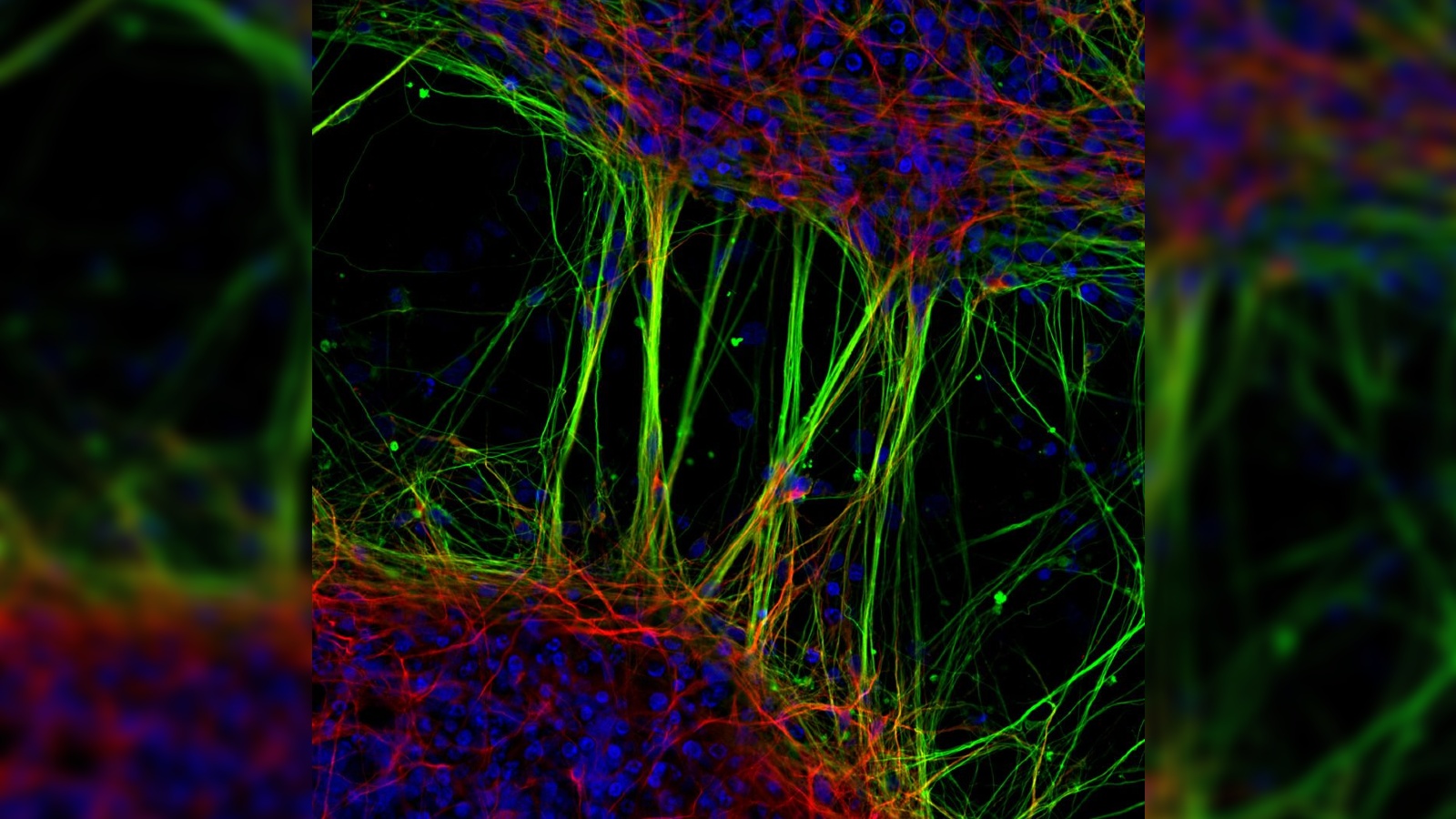

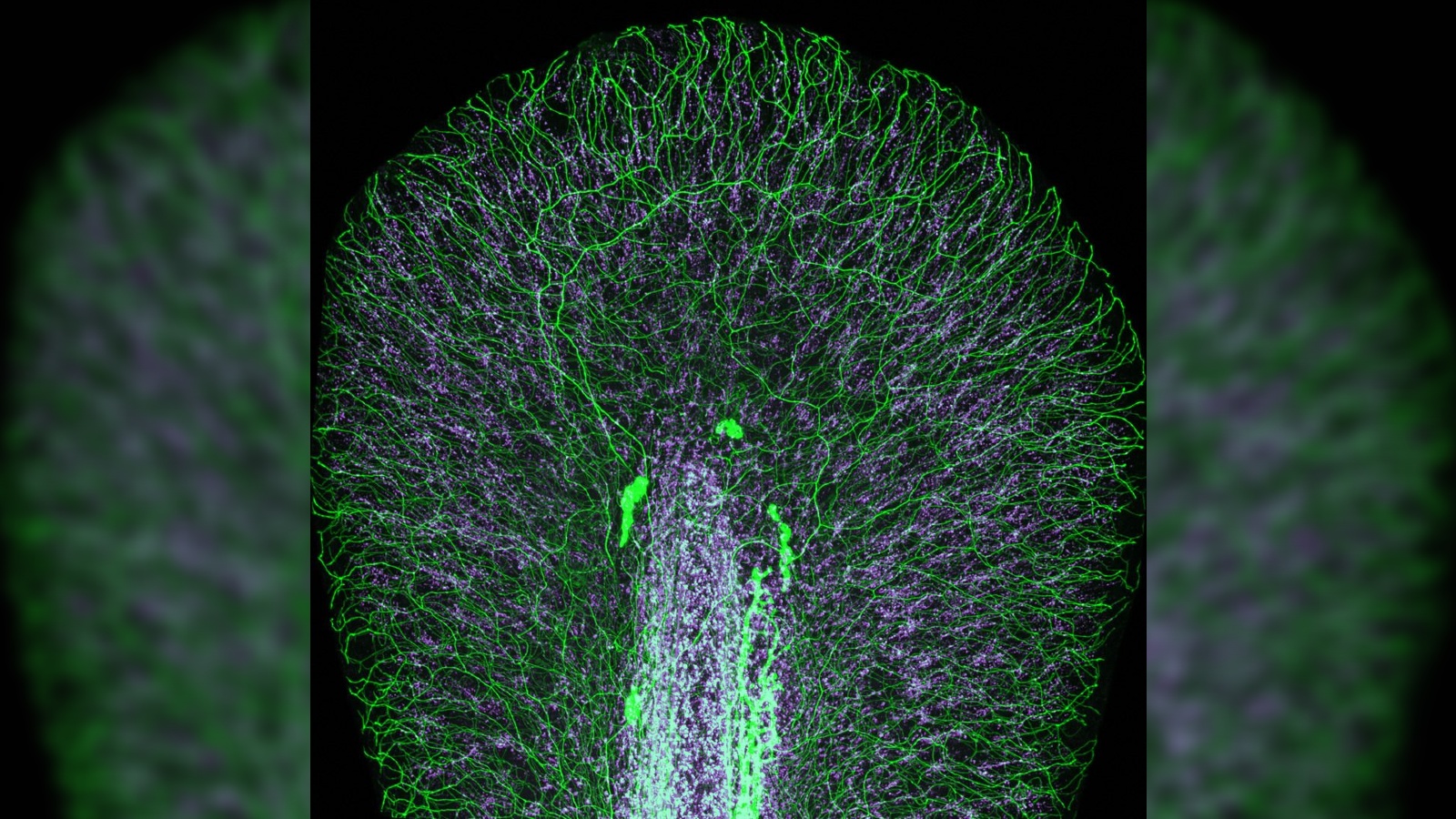

Other noteworthy images include a multi-colored mural of human neurons derived from stem cells, a neatly stacked tower of moth eggs and the luminous network of nerve cells inside a zebrafish embryo's tail.

Past winners of Nikon's Small World competition include a helix-shaped plankton, a mosquito's heart and a fluorescent, rainbow-colored turtle embryo.

On Sept. 13, the winners of Nikon's Small World in Motion competition — the sister competition that focuses on the very best microscopic videos produced by scientists and photographers — announced its winners. The standout video was a "completely hypnotic" donut of swirling cell microtubules.

Editor's note: This article was updated Oct.12 at 4:35 a.m. ET to correct the age of the dinosaur bone fragment following new information received from the photographer.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus