7,500-year-old Spanish 'Stonehenge' discovered on future avocado farm

It's one of Europe's largest Neolithic standing stone complexes.

Archaeologists have unearthed one of Europe's largest Neolithic standing stone complexes near the city of Huelva in southwestern Spain, ahead of plans to grow avocados there.

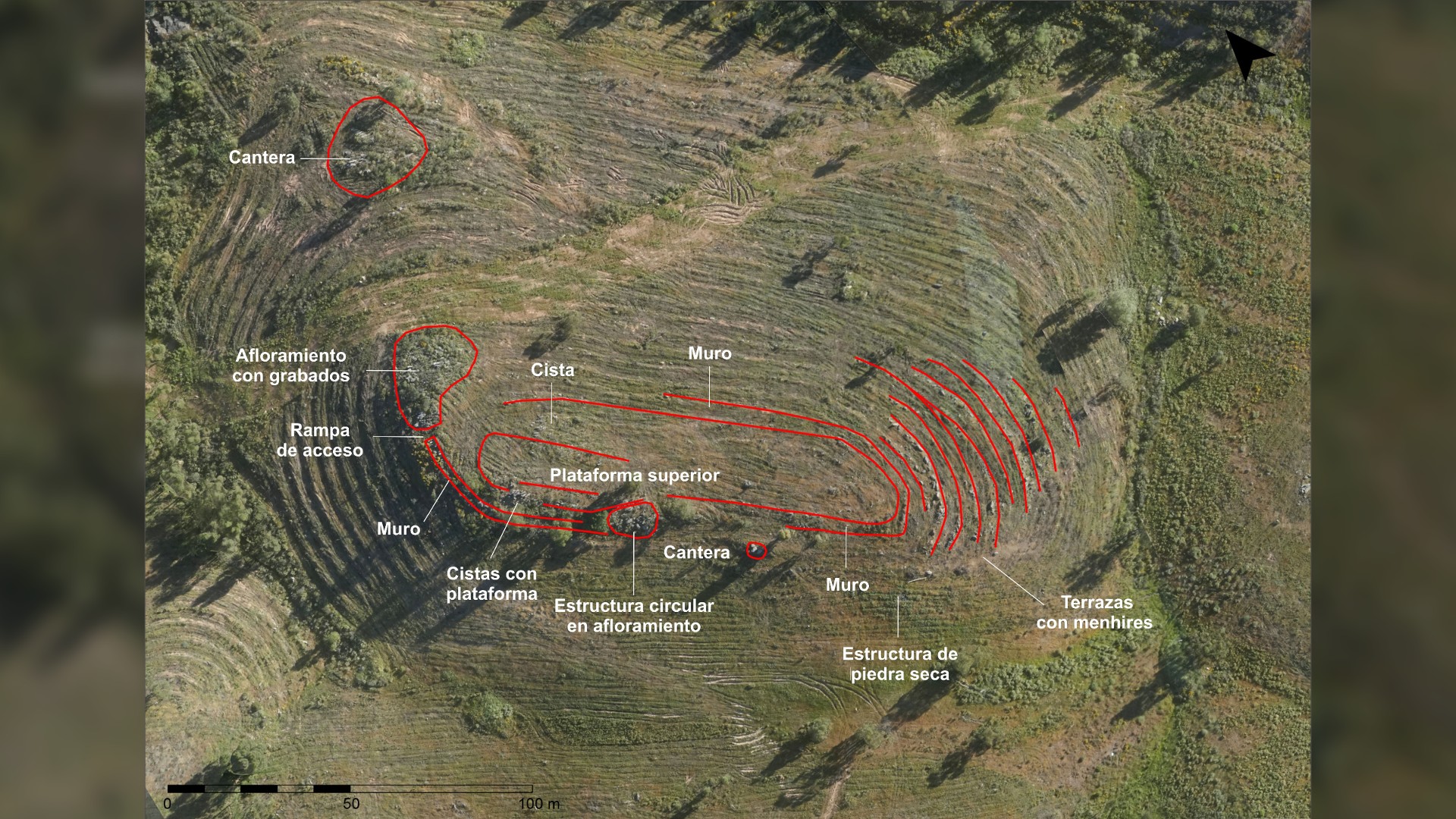

The oldest upright stones — called "menhirs" in many parts of Europe, possibly from a Celtic word for "stone" — could be up to 7,500 years old, and the entire complex consists of thousands of individual stones spread out over 1,500 acres (600 hectares) of the sides and top of a small hill.

Some of the largest stones stand alone, but others were positioned to form tombs, mounds, stone circles, enclosures and linear rows. The diversity of the structures is part of the puzzle of the site.

"This pattern is not common in the Iberian Peninsula and is truly unique," said José Antonio Linares, a geoarchaeologist at Huelva University and the lead author of a new study published in the June issue of Trabajos de Historia.

Related: Back to the Stone Age: 17 key milestones in Paleolithic life

The site, known as La Torre-La Janera, was discovered in 2018, but archaeologists only recently learned about the full extent of the Neolithic, or New Stone Age complex, Antonio Linares Catela told Live Science in an email.

It now seems that the functions of the Neolithic monuments were as varied as their construction. "Territorial, ritual, astronomical, funerary… the whole constituting a mega-site of the recent prehistory of southern Iberia," he said. This was a "megalithic sanctuary of tribute, worship, and memory to the ancestors of long ago."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Megalithic monuments

The landowner, a farmer, had wanted to establish an avocado plantation at the site, near the border of Portugal about 50 miles (80 kilometers) northwest of Huelva, Linares said.

But there were local rumors that menhirs had once stood on the hill, so it wasn't a complete surprise when an initial archaeological survey in 2018 confirmed there were several standing stones there. A full study in 2020 and 2021 revealed the site's importance, and the universities of Huelva and Alcalá are now funding an archaeological investigation until at least 2026, he said.

Neolithic people constructed the complex on a prominent hill not far from the mouth of the Guadiana River and the Atlantic Ocean, with good visibility over the surrounding territory.

So far, archaeologists have found more than 520 standing stones at the site, and some of the earliest may have been erected as long ago as the second half of the sixth millennium B.C., or about 7,500 years ago, while the latest Neolithic structures were built in the second millennium B.C., or between 3,000 and 4,000 years ago, he said.

Several of the standing stones created prominent roofed tombs known as "dolmens," while others formed coffin-shaped structures known as "cists," which the archaeologists expect were used to bury the remains of the dead.

But no human remains have yet been verified at the site. "We have not carried out extensive excavations of the tombs," Linares said; and while such structures must have contained skeletal remains at some point, bones may not have been preserved in the acidic soil.

Neolithic peoples and megaliths

Standing stones and other Neolithic monuments — known as "megaliths," from the ancient Greek words for "giant stone" — abound throughout Europe, from Sweden to the Mediterranean. Many megalithic sites have also been found in Spain, including in the region near La Torre-La Janera.

Some of the most famous, such as Stonehenge, are found in Britain, but even larger "megalithic" structures are found elsewhere — such as at Carnac in France's Brittany region, where there are more than 10,000 menhirs aligned in rows.

Related: Why was Stonehenge built?

The precise dates of such megalithic structures can be hard to ascertain because rock itself cannot be reliably dated. But the indirect evidence of other materials buried at the same sites suggest that most of them date to the Neolithic period from about 6,500 years ago, according to Smithsonian magazine — which would make the oldest standing stones at La Torre-La Janera more ancient than most.

Archaeologists suspect that the practice of building megalithic monuments spread over Europe during the Neolithic with successive waves of settlers, perhaps from the Near East, who seem to have assimilated the indigenous hunter-gather peoples, according to a 2003 study in the journal Annual Review of Anthropology.

Many megaliths seem to be aligned with certain astronomical events, such as the midwinter sunrise, and it seems many of those at the La Torre-La Janera complex may be, too.

The roofed tombs, or dolmens, "are generally oriented to the solstices and equinoxes, but there are also solar orientations in the alignments [rows of stones] and the cromlechs [circles of stones]," project leader Primitiva Bueno Ramírez, a professor of prehistory at Alcalá University near Madrid and a co-author of the new research, told Live Science.

She stressed that only the surface of the La Torre-La Janera site had been investigated so far, and archaeologists expect to find much more there.

One clue that more stones are yet to be found is the "magnificent preservation" of the structures, which may help the scientists recover information about the "occupations, chronologies, uses, and symbolism of these monuments," she told Live Science in an email.

Originally published on Live Science.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus