Fetus inside Egyptian mummy was 'pickled like an egg,' researchers say

However, some experts question whether the mummy was even pregnant at all.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Researchers studying the remains of what they believe to be a fetus found inside a pregnant mummy from ancient Egypt say the developing infant was slowly "pickled like an egg" over centuries as the mom's uterus became increasingly acidic.

However, not everyone in the field is convinced. One expert told Live Science that they are skeptical of the new findings and suggest the mummy may not have been pregnant. But if the finding is verified, it could change the way researchers study mummies in the future and potentially help identify other pregnant mummies.

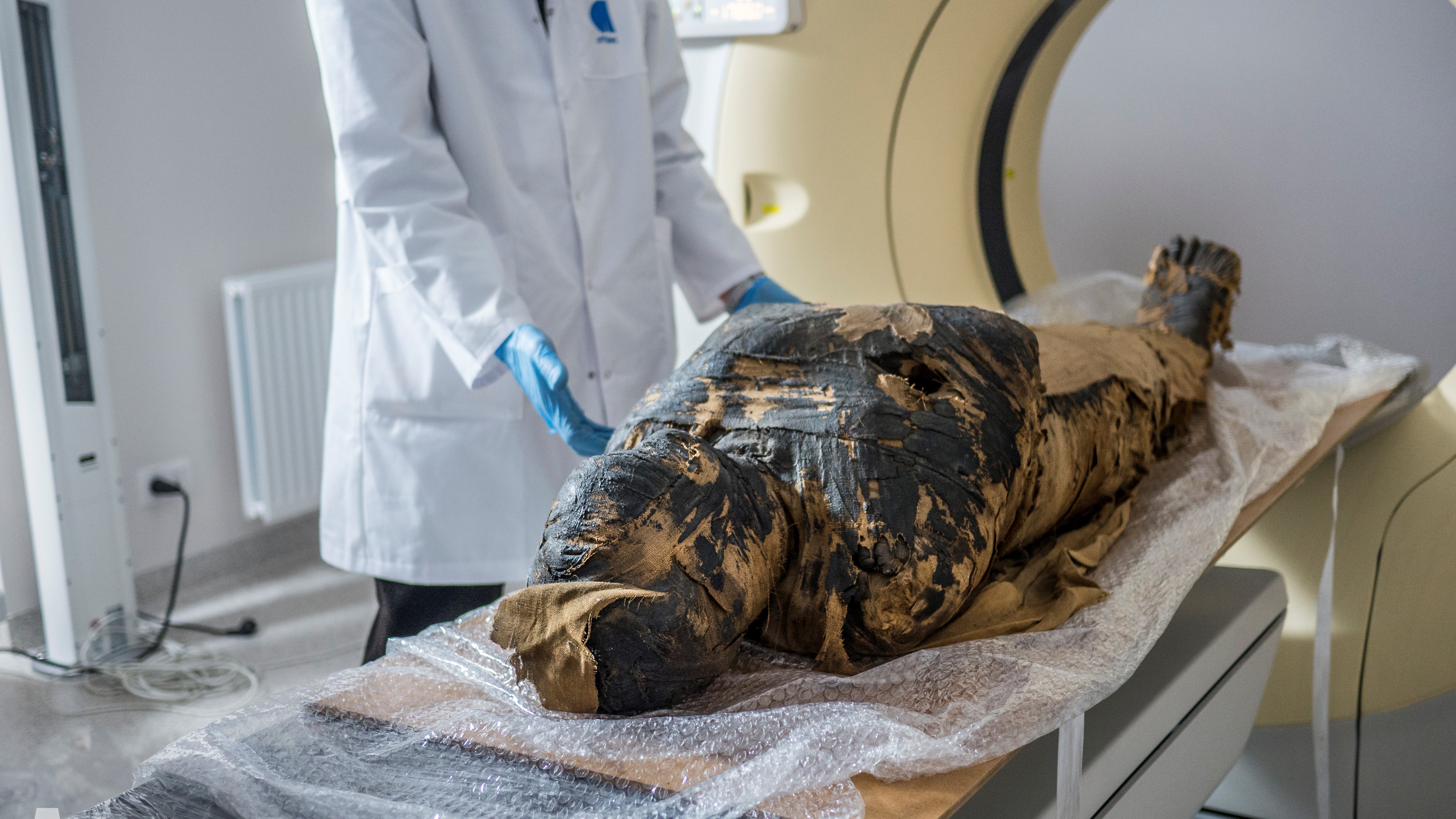

In April 2021, researchers from the Warsaw Mummy Project in Poland released a paper announcing the discovery of the first known pregnant mummy, which they called the Mysterious Lady, Live Science previously reported. The mummy, which dates back to the first century B.C., was found inside a coffin thought to belong to a male Egyptian priest, but X-ray and CT scans of the mummy revealed that the remains belonged to a female. The scans also highlighted a structure in the mummy's abdomen that the researchers believed to be a fetus, which they estimated was around 28 weeks old.

Article continues belowRelated: 7 amazing archaeological discoveries from Egypt

In the new study, carried out by the same team that first discovered the Mysterious Lady, researchers focused on explaining why the fetus had no skeletal bones nor a defined body shape. The Polish team proposed that the mom's uterus would have become acidic over time due to the mummification process and that acidity would have slowly dissolved the fetus's bones, leaving behind a deformed lump of mineralized tissue seen in the mummy scans.

The researchers said the process that destroyed the fetus is similar to how an egg might be pickled. "It is not the most aesthetic comparison, but conveys the idea," the team wrote in a blog post.

Pickled like an egg

The Polish team's new proposal is based on the idea that the human body becomes more acidic (or has a lower pH) as it decomposes. Without oxygen input in the body, the chemical reactions that occur produce acidic compounds, such as formic acid. "Blood pH in corpses, including content of the uterus, falls significantly, becoming more acidic," the researchers wrote.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers said the acidification process is more severe in mummies because natron, a naturally occurring salt that was packed in and around the body during the mummification process, creates a barrier that traps the acid inside certain places, such as the uterus. "The end result is an almost hermetically sealed uterus containing the fetus," the researchers wrote.

The acidic conditions inside the mummy's uterus would not have been strong enough to dissolve fully formed human bones. However, they could have dissolved fetal bones because "mineralization [of bones] is very weak during the first two trimesters of pregnancy and accelerates later," the researchers wrote. However, the rest of the soft tissues making up the fetus would have stayed largely intact.

"Picture putting an egg into a pot filled with an acid," the researchers wrote. "The eggshell is dissolving, leaving only the inside of the egg and the minerals from the eggshell dissolved in the acid." This is not how pickled eggs are traditionally made — the egg is normally cooked and de-shelled before being pickled in acid — but it does illustrate what may have happened to the fetus's bones.

The researchers think the minerals from the dissolved bones may then have been deposited into the soft tissue of the fetus, which would have deformed without any skeletal structure, creating the strange mineralized structure seen today.

Controversial claim

The research team published this study in response to criticism of their initial 2021 paper describing the discovery of the Mysterious Lady. The study's main critic was Sahar Saleem, a mummy expert and professor of radiology at Cairo University in Egypt. Saleem was skeptical that the fetus was legitimate because of a lack of physical evidence, such as bones. And, despite the new paper, Saleem remains unconvinced and questions whether the mummy was pregnant.

"In their response, the Polish team failed to address my concerns or identify any evidence of anatomical structures to justify their claim of a fetus," Saleem told Live Science. She thinks that the pickling theory only explains why there is no sufficient physical evidence of the fetus and that it does not provide any additional proof that the structure is a fetus at all.

Nor does the new paper explain why the uterus and alleged fetus were left inside the mummy in the first place. That would have been very unusual in ancient Egypt, where removing such structures and organs was part of the mummification process, Saleem said. If the body had become acidic enough to start dissolving the fetus's bones, the rest of the mummy's body, in particular its bones, would not have been so well preserved, she added.

Rather, Saleem suggested that the mineralized structure inside the mummy's abdomen is likely to be embalming packs, which were often placed in the abdomen of mummies after the insides were hollowed out. That is a more logical explanation than the Polish researchers' pickling theory, she added.

"When preparing our original publication, we counted on a scientific discussion in academic journals, so Professor Saleem's reply to our paper was most welcomed," Ejsmond Wojciech, lead author of the new study and co-director of the Warsaw Mummy Project, told Live Science. Feedback from other researchers is a vital part of the scientific process, he added.

However, the researchers have "mixed feelings" about Saleem's continued opposition to their newest paper. Radiologists like Saleem focus too much on looking for bones and are not open to any other explanations, Wojciech said. "What we discovered is something completely new and unparalleled," and has been well received by the scientific community, he added.

Next steps

The Warsaw Mummy Project team is planning further studies to support their claims, and the researchers hope additional evidence will win over critics such as Saleem, Wojciech said.

The researchers remain confident that they are correct about the mummy's pregnancy and what happened to the fetus. They also think that if other female mummies were reexamined, there would be a good chance that some of them would also have been pregnant.

"There is a very high probability that there may be mummies of pregnant women in other museum collections," the researchers wrote. "It is only a matter of time before the next mummified pregnant woman is discovered."

The study was published online Jan. 14 in the Journal of Archaeological Science.

Originally published on Live Science.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus