'Magnetic anomalies' may be protecting the moon's ice from melting

The moon lost its magnetic field billions of years ago. What are these strange pockets of magnetism on its surface?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

In 2018, NASA astronomers found the first evidence of water ice on the moon. Lurking in the bottom of pitch-black craters at the moon's north and south poles, the ice was locked in perpetual shadow and had seemingly survived untouched by the sun's rays, potentially for millions of years.

The discovery of water ice came with a fresh mystery, however. While these polar craters are protected from direct sunlight, they are not shielded from solar wind, waves of charged particles that gush out of the sun at hundreds of miles a second. This ionized wind is highly erosive and should have destroyed the moon's ice long ago, Paul Lucey, a planetary scientist at the University of Hawaii, told Science. And unlike Earth, the moon no longer has a magnetic shield to protect it from the brunt of these charged particles.

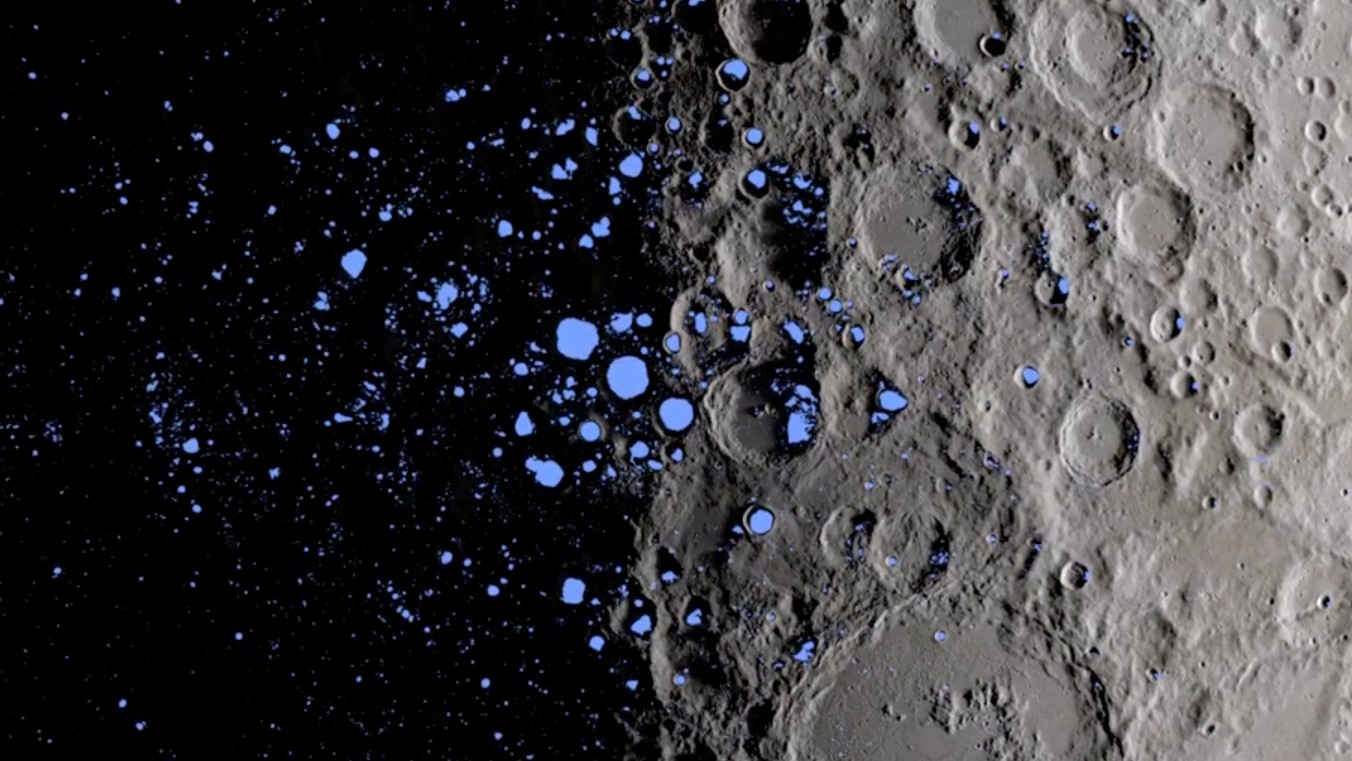

How, then, had the moon's polar ice survived? A new map of the moon's south pole — and the strange pockets of magnetic field that lie there — may provide an answer.

In research presented at the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference last month, scientists from the University of Arizona shared their map of magnetic anomalies — regions of the lunar surface that contain unusually strong magnetic fields — sprinkled across the moon's south pole. These anomalies, first detected during the Apollo 15 and 16 missions in the 1970s, are thought to be remnants of the moon's ancient magnetic shield, which likely disappeared billions of years ago, according to NASA.

The magnetic anomalies overlap with several large polar craters that sit in permanent shadow and may contain ancient ice deposits. According to the researchers, these anomalies may be serving as tiny magnetic shields that protect lunar water ice from the constant bombardment of solar wind.

"These anomalies can deflect the solar wind," Lon Hood, a planetary scientist at the University of Arizona, told Science. "We think they could be quite significant in shielding the permanently shadowed regions."

In their research, the authors combined 12 regional maps of the lunar south pole, originally recorded by Japan's Kaguya spacecraft, which orbited the moon from 2007 to 2009. Included among the spacecraft's science tools was a magnetometer capable of detecting pockets of magnetism across the lunar surface.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

With their composite map in hand, the researchers saw that magnetic anomalies overlapped with at least two permanently shadowed craters — the Shoemaker and Sverdrup craters — at the lunar south pole. While these anomalies are only a fraction of the strength of Earth's magnetic field, they could still "significantly deflect the ion bombardment" of solar wind, the researchers said in their presentation. (The team's research has not been published in a peer-reviewed journal.) That could be the key to the moon's long-lasting water ice.

No one is certain where the moon's magnetic anomalies came from. One theory is that they date back about 4 billion years, to when the moon still had a magnetic field of its own, according to a 2014 paper written by Hood in the Encyclopedia of Lunar Science reference book. When large, iron-rich asteroids crashed into the moon during this era, they may have created magma surfaces that slowly cooled over hundreds of thousands of years, becoming permanently magnetized by the moon's magnetic field in the process.

Upcoming lunar missions could shed light on the lunar south pole's pitch-dark ice deposits. The Artemis missions, which will ultimately return humans to the lunar surface for the first time since 1972, plan to land astronauts at the lunar south pole and establish a permanent base there. Studying the ice deposits in this region could reveal how they were created and why they've lasted so long.

Read more about this ancient magnetic field at Science.

Originally published on Live Science.

Brandon is the space / physics editor at Live Science. With more than 20 years of editorial experience, his writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. His interests include black holes, asteroids and comets, and the search for extraterrestrial life.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus