'First of its kind' triple star system likely gobbled up a 4th star

The unusual trio is much more massive and compact than similar systems.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Astronomers have detected a triple star system that is unlike any that has been seen before. The unusual trio of stars is much more massive and closely squeezed together than a typical triple system, which may be because the stellar triplets used to have a fourth sibling before one of the others gobbled it up.

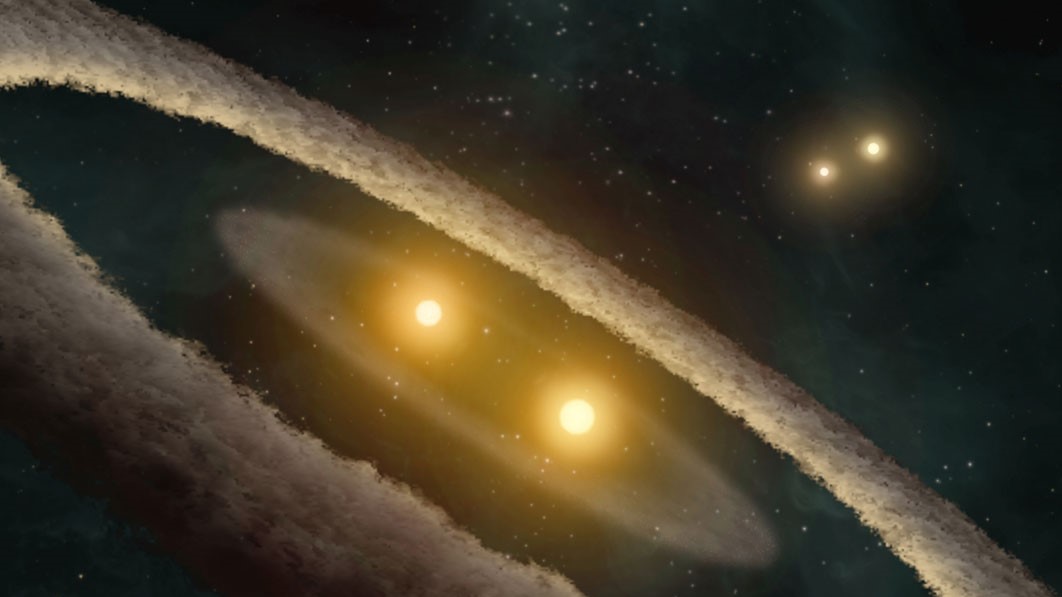

The triple, or tertiary, star system is known as TIC 470710327 and was detected by researchers using data from NASA's Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) observatory that’s orbiting Earth. The trio has a hierarchical structure, meaning a pair of binary stars circle one another at the center of the system, while a third star orbits the central pair.

Triple star systems are not that uncommon: As many as 10% of star systems in the universe could be tertiary, according to NASA. In September 2021, astronomers detected a single exoplanet orbiting a tertiary system for the first time, suggesting life could potentially exist in these systems.

However, TIC 470710327 stands apart from all the other known tertiary systems because of its size and shape. The stars are much more massive than the typical stars found within a tertiary system, which also means the trio is much more compact because they all exert a stronger gravitational pull than normal.

Related: Newly discovered 'micronovae' shoot out of the magnetic poles of cannibalistic stars

"As far as we know, it is the first of its kind ever detected," lead study author Alejandro Vigna-Gomez, an astrophysicist at the Niels Bohr Institute at the University of Copenhagen in Denmark, said in a statement.

The binary pair of stars at the heart of TIC 470710327 has a combined mass of around 12 times the sun, and it takes just over one day for the two stars to orbit one another. The larger outer star is even more massive, weighing about as much as 16 suns, and it orbits the binary pair once every 52 days, which is "pretty fast, when you consider the size of them," Vigna-Gomez said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The new system was originally found by a citizen scientist, who was combing through the TESS database in search for abnormalities. The star system stood out to the amateur astronomer due to its high luminosity, a consequence of having three stars shining brightly rather than one. However, it wasn't until the researchers later assessed the data that they realized it was a tertiary system. After discovering how massive the stars were, the team then began trying to figure out how the unusual system might have formed.

There are three potential explanations for how TIC 470710327 was created. The first possibility is that the large outer star formed first, and the smaller stars formed later. This is perhaps the most unlikely explanation, as the massive star would likely have ejected or absorbed the gas needed to form new stars, researchers said. The second option is that the three stars all formed separately and gradually gravitated to each other until they started orbiting each other. This is also unlikely because the massive outer star would likely have ended up at the center of the system.

The third explanation is that the system was originally made up of two binary pairs — the one at the center of the system we see today and another pair orbiting where the more massive outer star currently sits. Researchers suspect that the outer binary pair then underwent a stellar merger to create a single, more massive star.

Based on extensive computer simulations, the team found that this third explanation best explained the massive size and compactness of the stars.

The researchers want to continue searching for similarly massive and compact tertiary systems. "What we really want to know is whether this kind of system is common in our universe," study co-author Bin Liu, an astrophysicist at the Niels Bohr Institute, said in the statement. "Maybe there are more compact systems buried in the data."

The study was published online June 29 in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Originally published on Live Science.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus