Shark gets stabbed in the head, washes ashore in Los Cabos

The suspects are a stingray, a marlin and a sailfish.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

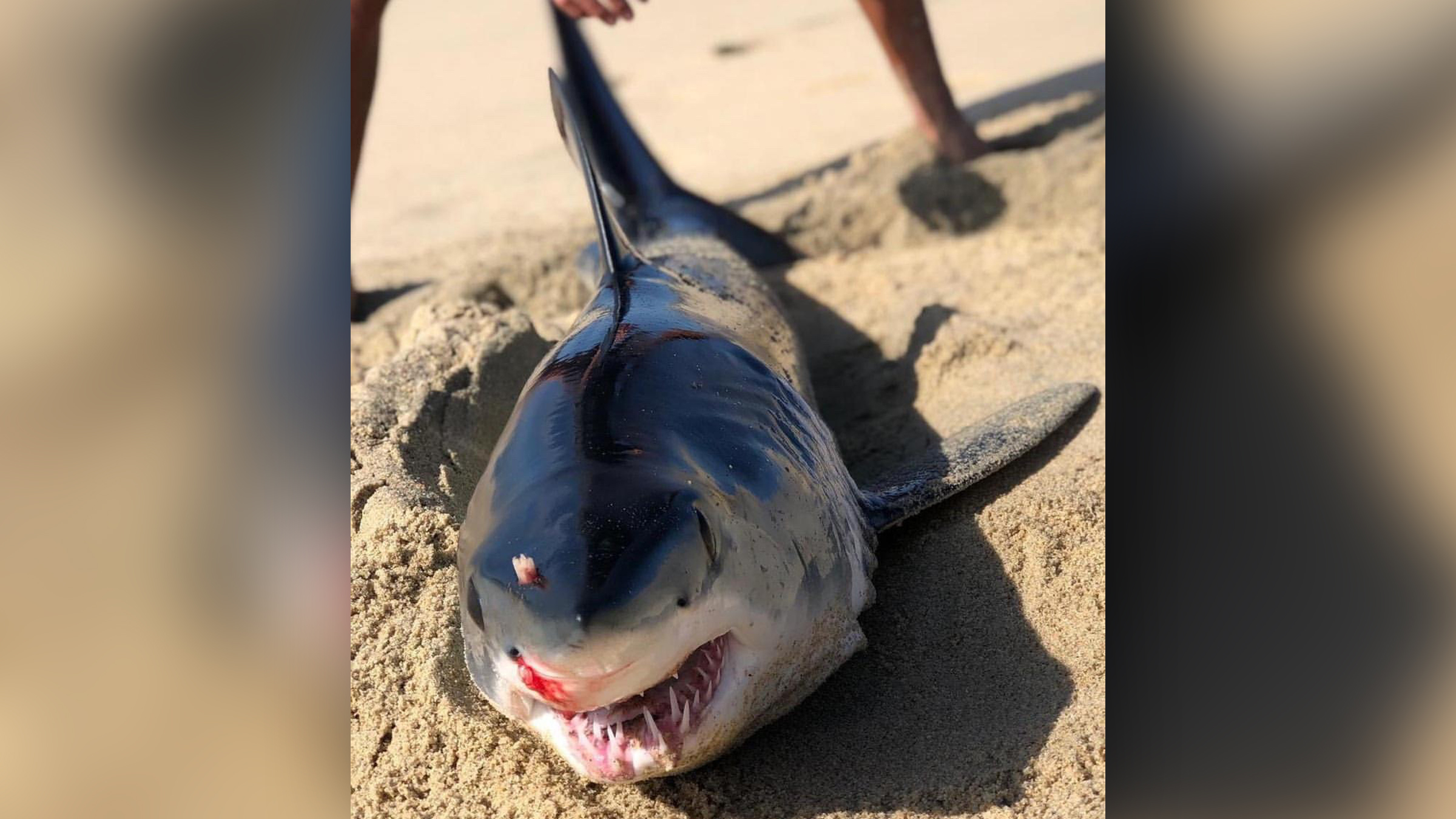

On a sunny day in February, a strange sight washed ashore on a beach in Los Cabos, Mexico: a dead shortfin mako shark that had been stabbed in the head.

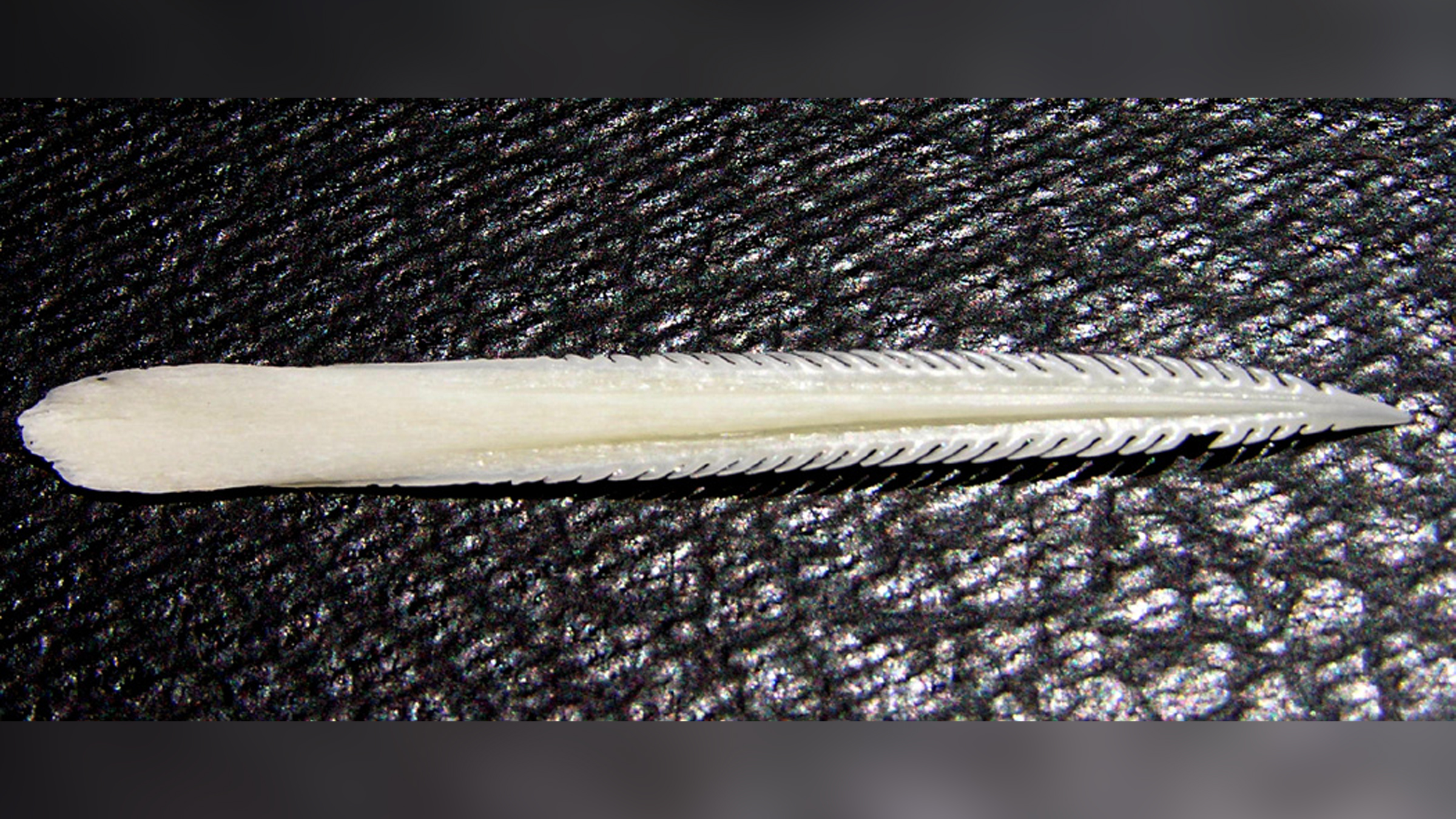

The weapon was still embedded in the young shark's head, but it's a mystery "whodunnit." Quite a few marine animals have pointy "swords" that they typically wield in self-defense. Based on the size of this particular spike, it could have been a marlin, a sailfish or even a stingray, all underwater inhabitants of the Los Cabos region, said Christopher Lowe, a professor of marine biology and director of the Shark Lab at California State University, Long Beach, who examined photos of the stabbed shark.

Adult mako sharks eat "sword"-bearing animals all the time. What likely happened here is that this juvenile shortfin mako shark (Isurus oxyrinchus) attempted to grab a meal but was unsuccessful, Lowe said. "This one was a young one — probably inexperienced and trying to take on prey that it wasn't really ready for," Lowe told Live Science.

Adult shortfin mako sharks can reach 12 feet (3.8 meters) in length and weigh at least at least 1,200 pounds (545 kilograms). But these sharks are born at about 3 feet (1 m) long, and this shark is only a bit longer than that, according to its photo, which is about the size of a 3-foot-wide (1 m) adult stingray.

Related: In photos: Mexico's new ocean reserve protects stunning biodiversity

The incident happened on Feb. 18, according to Arturo Chacon, who spotted the shark when he was walking along the beach in San José del Cabo, which, along with Cabo San Lucas, is known as Los Cabos, a popular tourist destination in northwestern Mexico. "It looked like it was fresh or that it lost its life not too long ago," Chacon, the owner and CEO of Tag Cabo Sportfishing, told Live Science.

He snapped a few photos of the shark and posted them on Instagram, writing, "A shark that washed out on the beach in San Jose del Cabo. Apparently because it lost a battle with a big stingray! Woow!"

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

While it's not clear what animal stabbed the shark, stingrays do have serrated, pointy spines. If it was a stingray, it was likely a pelagic stingray (Pteroplatytrygon violacea), a creature with a dark purplish to gray underside and a defensive spine, also known as a barb, on its tail that it uses to impale animals threatening it, Lowe said. The pelagic stingray lives in the open water, and its habitat overlaps with that of the shortfin mako shark, Lowe noted.

Stingray spines are venomous but rarely fatal, Lowe said. There are exceptions, however; in 2006, Australian television personality Steve Irwin, known for his popular show "The Crocodile Hunter," died when the venomous spine of a short-tail stingray (Dasyatis brevicaudata) pierced his heart. But it's not uncommon to see live sharks riddled with stingray spines: "In one shark, we've seen probably 15 to 20 spines," Lowe said.

Stingrays can get spined, too. Females sometimes use their spines to ward off amorous males, and once a stingray uses a spine, it can grow another, Lowe said. "If females are done mating, and males try to mate with them, they'll spine the crap out of them," Lowe said. "You'll see males with all these holes in them."

So, if spines usually aren't lethal, what killed the young mako?

Judging from the photos Chacon took, it doesn't look like the spine pierced the shark's brain, Lowe said. "It's hard to tell for sure, but [the spine] is so far forward — the brain is back more, kind of between the eyes," Lowe said. "Sharks' brains are weird. There's a lot of space and not a lot of brain in there. There's a lot of fluid that fills the chondrocranium, which is the braincase, and then the brain is relatively small."

Related: In photos: Glow-in-the-dark sharks

It's possible the spine damaged part of the shark's forebrain or olfactory lobes, "so it might have affected its ability to smell," Lowe said. "Whether that was lethal or not, we'd have to do a necropsy [an animal autopsy] on it."

What's surprising here is that the shark was found on the beach. Sharks are negatively buoyant, so they usually sink to the ocean floor when they're dying, Lowe said. "What I would infer based on this wound is that the animal was disoriented and swam into the shoreline, where it beached itself," he said. Or, perhaps after the shark was stabbed, "a fisherman caught it and it got off the hook, but it was so beat up, it just didn't make it," Lowe said.

After analyzing the photos more, Lowe said the spine might not belong to the pelagic stingray. "Stingray barbs tend to be more oblong or flattened, but this looks too thick in diameter," he later wrote to Live Science in an email. "Another possibility is it is the tip of the bill from a marlin or sailfish."

These sword-carrying fish are known to stab sharks that are trying to eat them, Lowe said. But that's not always the case. In 2020, a thresher shark (Alopias superciliosus), a shark that doesn't prey on swordfish, washed ashore in Libya with a sword sticking out of its body, a study in the journal Ichthyological Research reported. It's unknown what happened, but scientists suggested that maybe the stabbing was accidental or that the swordfish attacked the shark because the two animals were competing for the same prey, Live Science previously reported.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus