Longest dinosaur neck ever stretched further than a school bus at 49 feet long

By comparing the few known bones of the sauropod Mamenchisaurus sinocanadorum with its relatives, experts have extrapolated its tremendous neck length.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The longest-necked dinosaur on record was a Jurassic beast with a 49.5-foot-long (15.1 meters) neck, a new study finds.

That's more than six times the length of a giraffe's neck and about 10 feet (3 m) longer than the length of a school bus. This long-necked sauropod, known as Mamenchisaurus sinocanadorum, lived about 162 million years ago during the Jurassic period in what is now the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of northwestern China, according to the study, published Wednesday (March 15) in the Journal of Systematic Palaeontology.

"The long neck of Mamenchisaurus sinocanadorum, like those of other sauropods, would have made the animal an efficient forager, able to graze on the huge volumes of browse necessary to fuel such a huge body before moving to the next vegetation-rich spot," study first author Andrew Moore, a paleontologist at Stony Brook University in New York, told Live Science in an email.

Researchers discovered M. sinocanadorum's fossils in 1987, but they didn't find much — only a jaw bone and some neck vertebrae and neck ribs. However, these were enough to tell paleontologists a lot about the long-dead dino. "All sauropods had long necks, but mamenchisaurids were standouts, with some of the most extreme neck proportions of anything in the history of terrestrial life," Moore said.

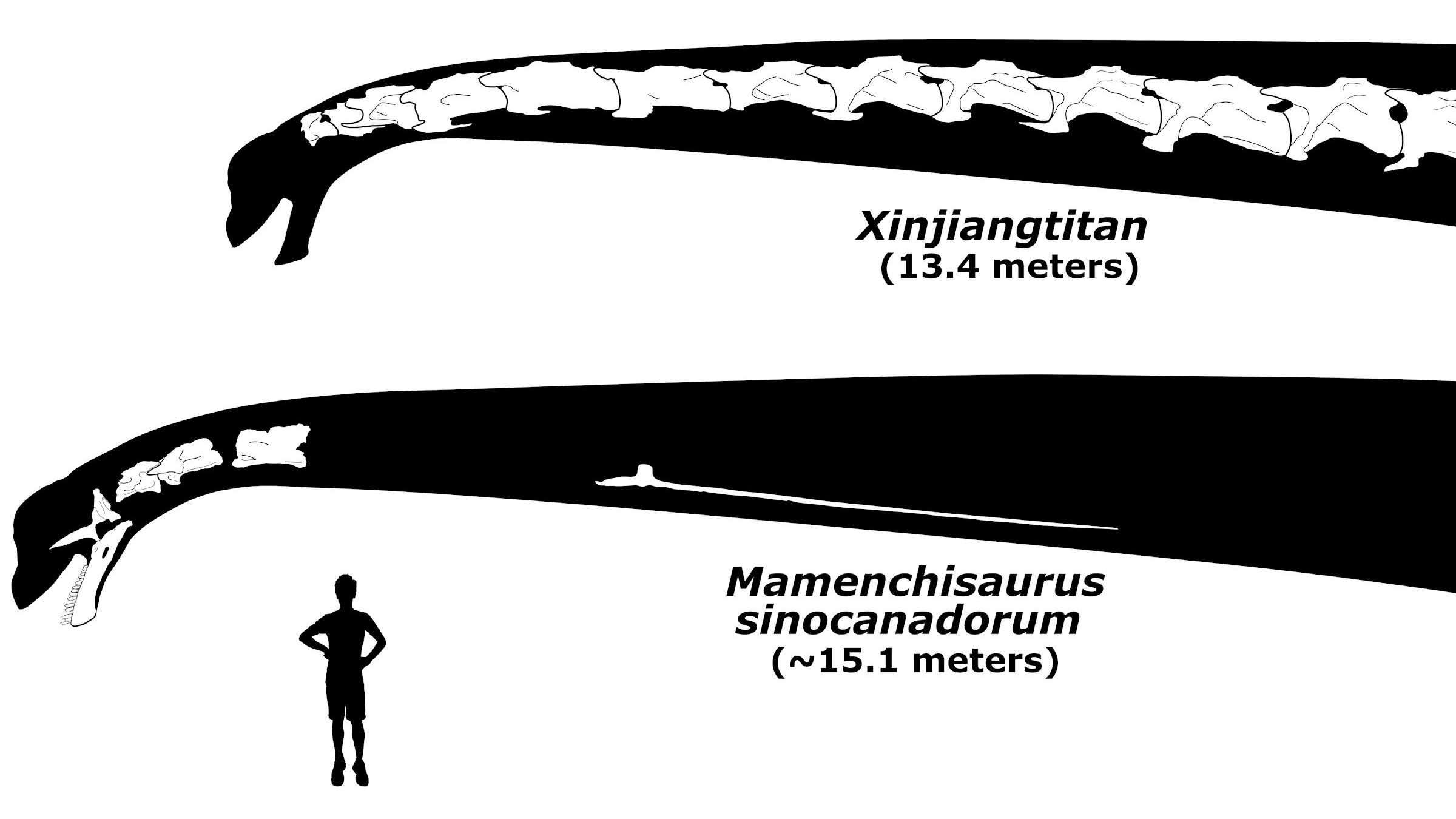

After M. sinocanadorum, the next longest-necked dinosaur is Xinjiangtitan shanshanesis, a mamenchisaurid that boasts the most complete preserved neck on record at 43.9 feet (13.4 m), Moore said.

Related: Long-necked dinosaurs probably had even longer necks than we thought

Moore and his colleagues compared the few preserved vertebrae of M. sinocanadorum with the more complete skeletons of its closest sauropod relatives. "Our analyses make us fairly confident that Mamenchisaurus sinocanadorum had 18 vertebrae in its neck, because close cousins known from more complete skeletons all have 18 cervical vertebrae," he said. "So focusing just on these close relatives with similar necks, we scaled up."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

M. sinocanadorum evolved to keep its tremendous neck lightweight but sturdy. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the dinosaur's vertebrae revealed that air made up as much as 77% of their volume, just like the light skeletons of today's storks. To protect its neck against injury, the sauropod had 13-foot-long (4 m) ribs in its neck that were built like rods and overlapped in bundles on both sides of the neck, much like those on other sauropods, the researchers found.

It's unknown why M. sinocanadorum evolved to have such a supersize neck, but "perhaps it made them that much more efficient at foraging," Moore said. Sporting a long neck may have also helped the giant herbivore shed excess body heat by increasing its surface area, just like how elephants' enormous ears help keep them cool.

The new study is "pretty exciting," Mike Taylor, a research associate in the Department of Earth Sciences at the University of Bristol in the U.K., told Live Science in an email. Taylor was not involved in the study but has studied sauropod necks.

"It's funny to think that only a few decades ago, the longest known necks were those of Giraffatitan brancai, Mamenchisaurus hochuanensis and Barosaurus lentus (all about 9 m [29.5 feet]) and now we're seeing solid evidence for necks at least half as long again, maybe much longer," Taylor said.

Besides the mechanical challenge of holding up such a lengthy neck, sauropods also had to "breathe through those necks, circulate blood through them, innervate them, pass ingested food down them, regulate their temperature, and much more," Taylor added. "They really are the most astonishing structures in the whole of biology."

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus