'Chaos of clicks and sounds from below' as 70 orcas kill blue whale

The orcas were biting the blue whale's jaw, trying to grab its tongue.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

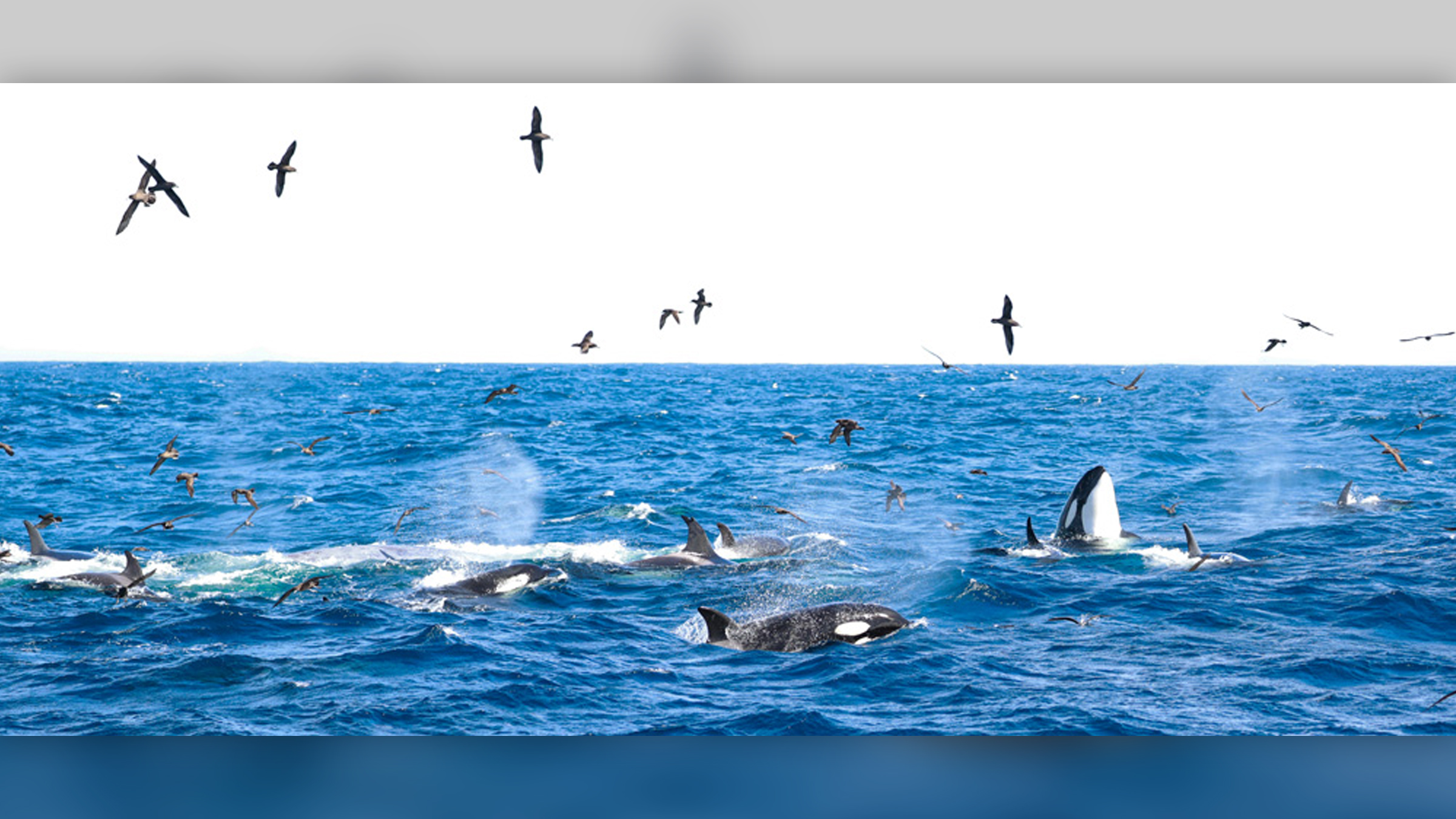

In an hours-long struggle, as many as 70 killer whales hunted down and killed a blue whale off the southwestern coast of Australia, according to a marine biologist who saw the "astonishing, a little bit disturbing and truly mind blowing" event take place.

At first, it seemed like a normal day of whale watching, said Kristy Brown, a marine biologist with Naturaliste Charters, a company that runs whale-watching tours in Western Australia. The vessel happened upon two pods of orcas in Bremer Bay Canyon, about 28 miles (45 kilometers) off the coast, that were "playing and surfing the waves," Brown wrote in a March 16 blog post.

But soon, people on the boat noticed that the orcas were creating nonuniform wave surges. This was odd; when orcas hunt beaked whales, for instance, they tend to move in unison, creating waves surging in one direction. "But this was different, these surges were scattered," Brown said. Then, around 11:30 a.m. local time, there arose "a long, high blow [spray] that stayed in the air … It was a blue whale, estimated to be 16 meters [52 feet] long, with plenty of years left to live."

Related: Photos: Orcas are chowing down on great-white-shark organs

It's unclear whether the prey was a juvenile blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus) or a pygmy blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus brevicauda), as "both use these waters," Brown told Live Science in an email. Regardless, the blue beast made a big mistake when it ventured alone into the canyon system, where orcas swim.

Despite their name, orcas (Orcinus orca), which are also called killer whales, are not whales. Rather, they're the largest species of the dolphin family, according to the Ocean Conservancy. And, like their "killer" name suggests, these marine mammals are known for hunting all kinds of prey, including humpback whales, seals, sea turtles and even great white sharks.

In this case, even though the blue whale was nearly twice the length of the largest orca, which can grow to lengths of about 31 feet (9.5 m), it couldn't shake off its pursuers. "It was completely surrounded by orca[s] as it swam," Brown wrote in the blog. Moreover, the orcas didn't appear to rush the hunt, but instead were "strategic, thoughtful, collaborative, patient [and] persistent," Brown wrote in the blog.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In cyclical waves, "multiple orcas were on the animal, jostling with it and swimming fast, beside and under it, whilst others dropped off the chase to rest in our wake and cruise along and beside the hunt, easily 200 m [656 feet] back," she said. It seemed that "tiring out the blue was their goal," she noted.

Meanwhile, more orcas kept arriving, and soon there were "at least six big males for different pods," Brown said. Each pod is home to between six and 12 orcas, so this showed the scale of how many orcas were involved in this hunt, she said. Even baby orcas, which were still yellow and red — colors that likely come from their blood vessels that have yet to be covered by thick blubber — "were there, in close, learning," Brown said.

As one large group, the orcas drove the blue whale from the roughly 3,280-foot-deep (1,000 m) Bremer Canyon system toward the shallower continental shelf, which is only about 262 feet (80 m) deep. Brown heard "the breaches and tail slaps above, and a chaos of clicks and sounds from below as the orcas pushed the blue forward."

Unlike the baleen blue whale, orcas have teeth, a weapon they used to chomp down on this blue whale's jaw. "As the whale spun and turned, the orcas held on — they wanted its tongue," Brown said. "[They] were waiting for the jaw to release, but it would not."

Related: Photos: Pilot whales in trouble off Everglades

The blue whale fought until the end. "It wouldn't give up, it went under, and for a moment we thought it was all over, yet again and again its tail would rise up, thick and silver in the dark ocean, surrounded by black and thundering fins," Brown said.

Just before 3 p.m. local time, after hours of this "feverish and chaotic" hunt, the blue whale succumbed to its attackers, Brown said. "A bubble of blood rose to the surface like a bursting red balloon," she recalled. After that, the orcas divided up "the carcass as it was shared with all involved in the depths below," Brown said. "We saw some blubber, only one hunk of flesh, and it was gone."

A hammerhead shark and long-finned pilot whales (another species of oceanic dolphin) tried to grab some of the whale meat, but the orcas fiercely guarded their prey. On the boat, "some patrons [were] in tears, some stunned silence, some excited and intrigued," Brown said.

This is the third time Naturaliste Charters has recorded orcas taking down a blue whale, Brown told Live Science in an email. "Both of these were in April 2019, and were two weeks apart," she said. In 2020, "our season last year was cut short due to COVID-19, so we were not at sea at the time when the blue whales were migrating north from Antarctica (mid-March, April, May), therefore we do not know if the same dynamic occurred last year."

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus