Model suggests how airborne coronavirus particles spread in grocery store aisles

Based on their findings, the researchers recommend avoiding busy indoor spaces.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Scientists in Finland have modeled how small airborne viral particles spread in a grocery store setting, which may help us better understand the spread of the new coronavirus.

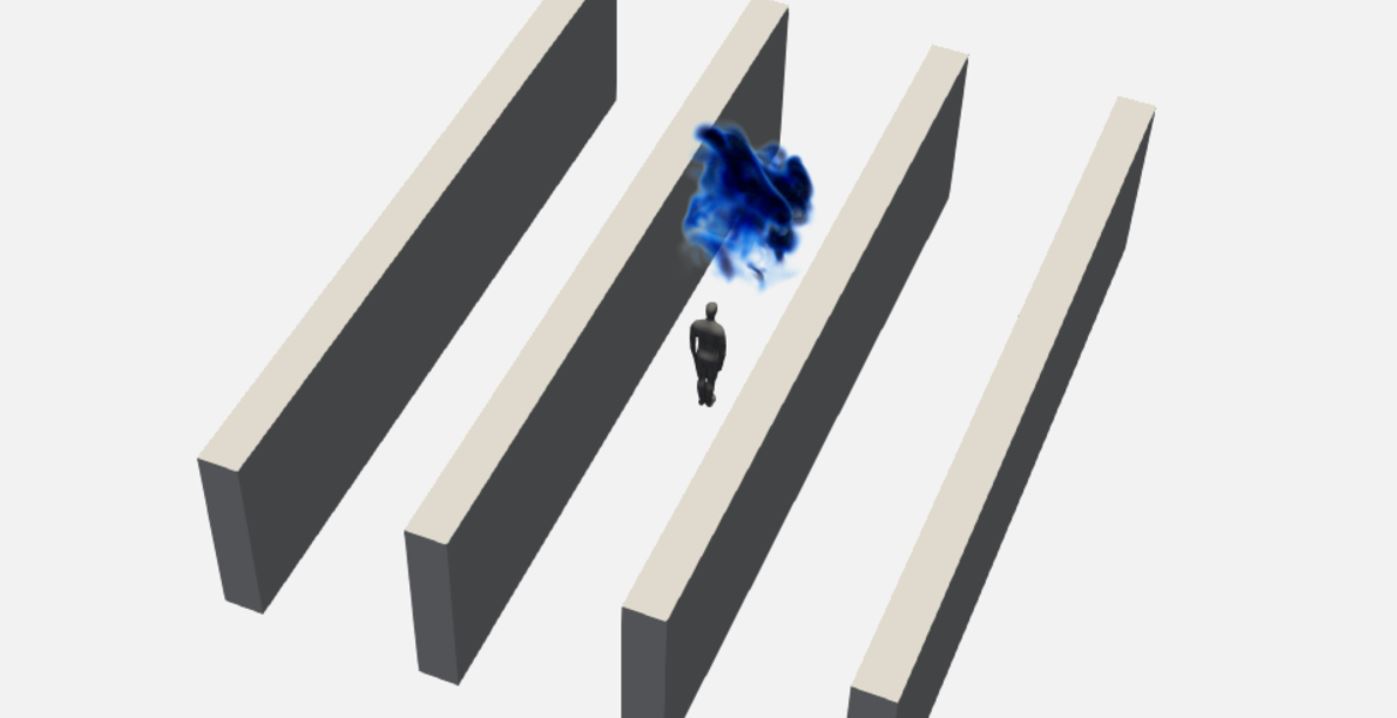

For the study, researchers at Aalto University, the Finnish Meteorological Institute, the VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland and the University of Helsinki used a supercomputer to simulate the spread of small viral particles leaving a person's respiratory tract through coughing. They simulated a scenario in which a person coughs in a store aisle between shelves, and took into account ventilation.

They found that, in this situation, an aerosol "cloud" spreads outside the immediate vicinity of the person coughing, and diluted as it spreads, the authors said. But this process takes up to several minutes, and in the meantime, a person who walks by could in theory inhale the small particles.

—Coronavirus in the US: Map & cases

—What are coronavirus symptoms?

—How deadly is the new coronavirus?

—How long does coronavirus last on surfaces?

—Is there a cure for COVID-19?

—How does coronavirus compare with seasonal flu?

—How does the coronavirus spread?

—Can people spread the coronavirus after they recover?

"Someone infected by the coronavirus can cough and walk away, but then leave behind extremely small aerosol particles carrying the coronavirus. These particles could then end up in the respiratory tract of others in the vicinity," Ville Vuorinen, and assistant professor in the Department of Mechanical Engineering at Aalto University, who studies fluid dynamics, said in a statement.

Based on their findings, the researchers recommend avoiding busy indoor spaces.

The researchers modelled the movement of aerosol particles smaller than 20 micrometers, which include particles small enough to remain suspended in the air (rather than falling to the floor) or move along air currents.

The researchers will continue to refine their modeling and develop visualizations to help better understand the movement of airborne particles.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

- The 12 deadliest viruses on Earth

- 11 ways processed food is different from real food

- 20 of the worst epidemics and pandemics in history

Originally published on Live Science.

OFFER: Save 45% on 'How It Works' 'All About Space' and 'All About History'!

For a limited time, you can take out a digital subscription to any of our best-selling science magazines for just $2.38 per month, or 45% off the standard price for the first three months.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus