Cancer sometimes triggers sudden memory loss — now we might know why

A virus-like protein made by some tumors may be the culprit behind an enigmatic neurological syndrome in cancer patients.

Cancer can sometimes trigger an off-the-rails immune response that harms nerve cells, rapidly leading to thinking problems and memory loss — but until now, scientists weren't sure what caused this rare complication.

This disorder is a type of paraneoplastic neurological syndrome (PNS), and researchers already knew it stems from the immune system's reaction to a tumor rather than the tumor itself. It occurs when a tumor sets off an autoimmune response that targets the brain and spinal cord.

Patients with this complication sometimes exhibit memory loss before the tumor is even detected, and the cellular damage caused by this autoimmune response can, in some cases, be worse than the cancer itself.

However, scientists didn't know what initially triggers PNS. Now, researchers have found that the autoimmune reaction is caused by the tumor releasing a protein that looks like a virus. The team published their findings Wednesday (Jan. 31) in the journal Cell.

Related: CRISPR used to 'reprogram' cancer cells into healthy muscle in the lab

Virus-like proteins and neurological damage

In patients with PNS, the body's own immune cells cause collateral damage to the nervous system, so these syndromes can occur even if no tumor is physically present within nerve tissue.

PNS can often occur even before cancer is known to be present and can be diagnosed using tests that look for "onconeural antibodies" in the patient. These antibodies are tied to both neurological symptoms and cancer, and they can therefore be used to help diagnose the cancer itself. What scientists didn't know is why the body creates these antibodies in the first place.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This mystery prompted Jason Shepherd, an associate professor in the Department of Neurobiology at the University of Utah, and his team to look at PNMA2, a gene that encodes a protein made almost exclusively in the brain. Antibodies target PNMA2 in patients with PNS who show signs of nervous system degeneration.

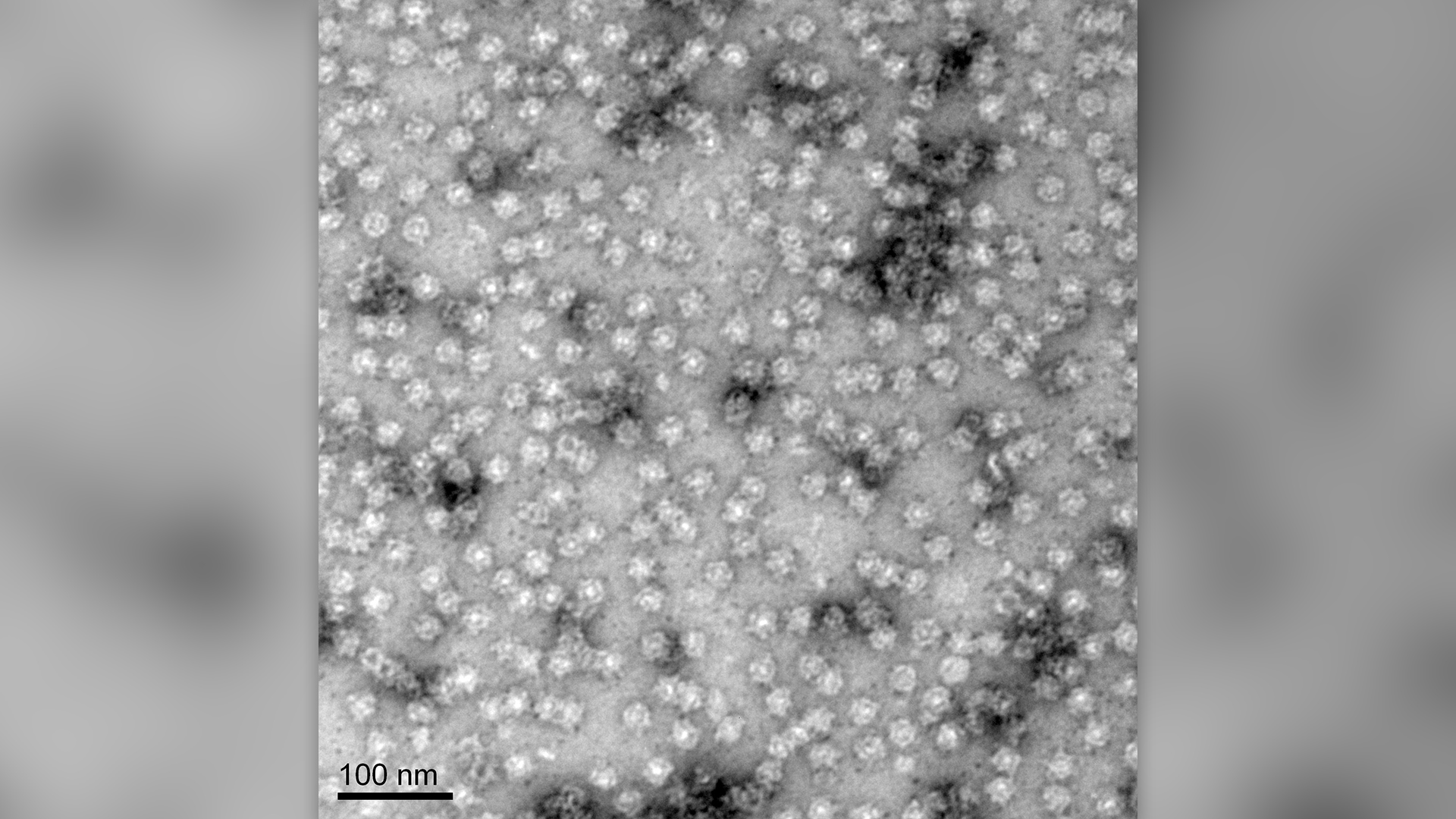

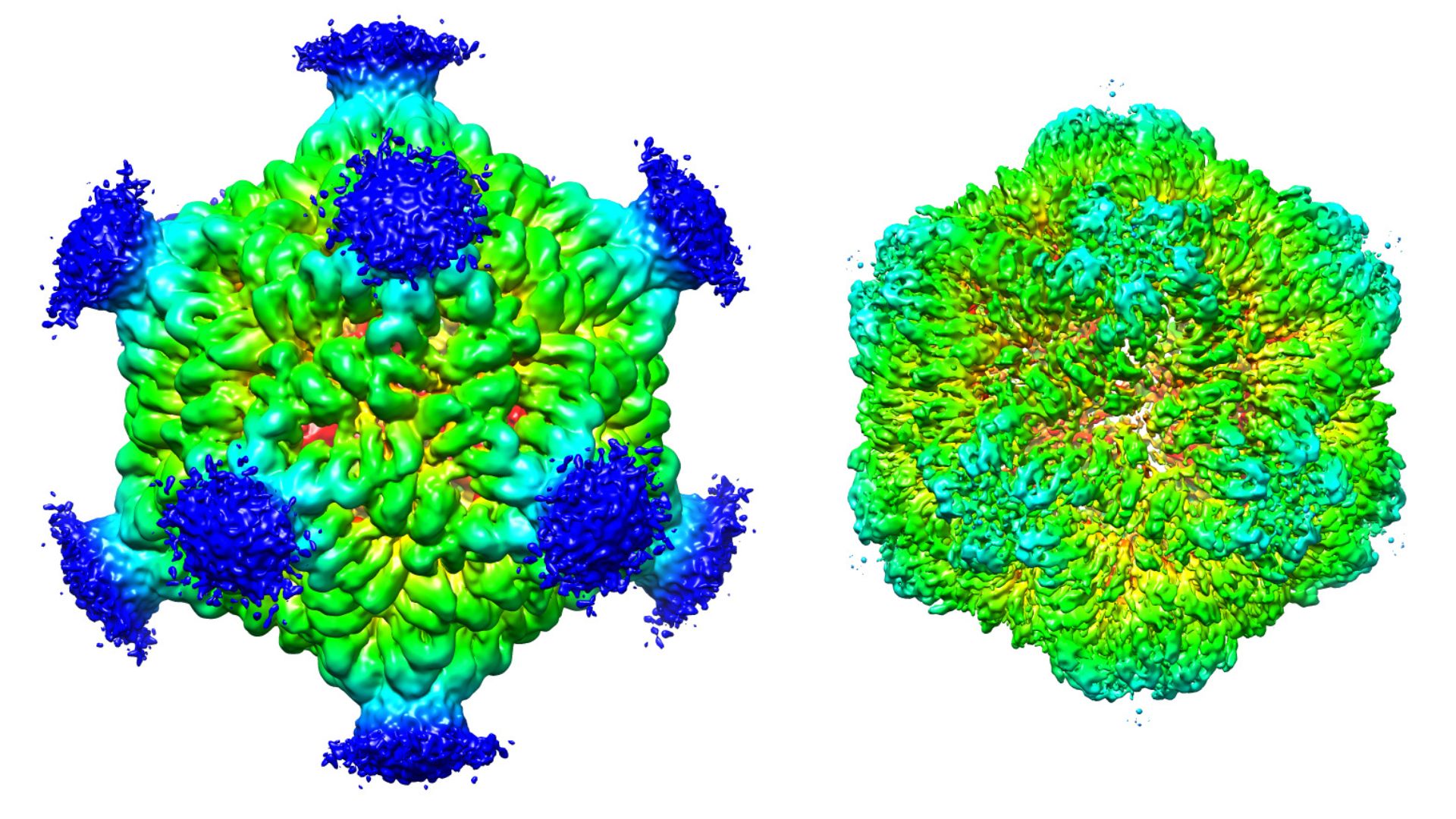

When observing the PNMA2 protein with an electron microscope, the researchers realized it looked very structurally similar to a virus. The team suggested that, because of its appearance, the body's immune system might mistake it for an invader and produce antibodies against it.

But PNMA2 is also found in the brains of people who don't have cancer — so what causes the immune system to attack it?

The researchers hypothesized that, if the protein is being made by the tumor outside the nervous system, the body might interpret it as being in the wrong place, sparking an immune response. They tested the idea by injecting mice in the abdomen with PNMA2 proteins. Not only did the rodents mount an immune response and make antibodies, but they also exhibited similar cognitive issues to cancer patients with the same antibodies.

Other proteins form virus-like protein structures, so why does PNMA2 cause such a severe reaction? Other virus-like proteins in the body are often shipped out of cells within enclosed membranes that let them evade the immune system, Shepherd told Live Science.

But with PNMA2, "what we found with these [proteins], they somehow get out of the cell without a membrane, which is kind of strange," he said. "I think that makes this viral-like protein even more immunogenic."

Related: DNA's 'topography' influences where cancer-causing mutations appear

When made in the brain, PNMA2 can avoid triggering an immune response, but if it's made elsewhere, there is no stopping the immune system from trying to attack.

"This paper presents an exciting premise that cancer induced immune response might be caused by the expression of viral-like particles encoded by PNMA2, that set off the host's viral response, specifically in neuronal tissue," said Travis Thomson, an assistant professor of neurobiology at the University of Massachusetts Medical School who was not involved in the work.

The study also poses interesting questions, such as whether any virus-like proteins made in the brain set off an immune response, Thomson told Live Science in an email.

"What keeps these viral like particles under control in healthy tissue?" Thomson said. "No doubt these and many more questions will be presented from this and other complementary studies."

In the future, Shepherd and his team plan to answer some of these questions and aim to study which aspect of the autoimmune response is most responsible for the neuron damage seen in patients. Figuring this out could point to future treatments.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to community@livescience.com with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!

Jennifer Zieba earned her PhD in human genetics at the University of California, Los Angeles. She is currently a project scientist in the orthopedic surgery department at UCLA where she works on identifying mutations and possible treatments for rare genetic musculoskeletal disorders. Jen enjoys teaching and communicating complex scientific concepts to a wide audience and is a freelance writer for multiple online publications.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus