The gender health gap: 10 times medicine failed women

In modern times, why is there still such a stark gap between the way women and men are treated when seeking healthcare?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The "gender health gap" describes the differential treatment women experience when seeking healthcare, compared to men, and the negative impacts this treatment has on women's overall health. This inequity partially stems from the "gender research gap," or the historic exclusion of women from medical research.

Until 1993, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) banned women "with child bearing potential" from participating in early-stage clinical trials, "except if these studies were being conducted to test a drug for a life-threatening illness," according to a 2016 report in the journal Pharmacy Practice. This was due to a 1977 FDA guideline that aimed to protect women's reproductive potential and ensured that most early-stage clinical trials at the time were male-dominated. Results of these trials were inappropriately applied to women and this has led to serious consequences, from incorrect drug dosages to health problems.

But it's not just a gender issue. Across the world, women from minority groups receive a lower standard of care in medical environments and are underdiagnosed in comparison to white women, sometimes with fatal consequences.

1: Drugs recall: 1997-2001

A 2001 audit of 10 prescription drugs withdrawn from the American market for safety reasons between 1997 and 2001 revealed that 80% posed a greater risk to women than men. According to the Government Accountability Office, some drugs get pulled after approval because their adverse side effects show up with more widespread use. Of these eight prescription drugs, four were prescribed more frequently to women, which the GAO notes may have led to a higher number of adverse events in women. The other four were prescribed equally between men and women but showed more adverse effects in women than men.

Of the two remaining withdrawn drugs, one belonged to a class of drugs known to pose a greater health risk for women, but the GAO was unable to directly link the adverse effects to gender alone and the GAO found no evidence that the health risks for the remaining withdrawn drug differed for women and men.

2. Ambien dosage

Ambien (generic name zolpidem) is a medication often used to treat insomnia. Following the drug's approval in 1993, the FDA investigated data spanning 26 years, and found 66 examples of complex sleep behaviors associated with Ambien and similar insomnia medications, releasing a black box label warning in 2019.

At the recommended dosage, blood Ambien levels were significantly higher in women than in men — 25% compared with 33%. This was of particular concern as this higher blood Ambien content put women at a higher risk of next-day driving impairment, according to the FDA. The dosage has now been amended, as of 2013, with women recommended to take 5 milligrams (mg) and men up to 10 mg for instant release medications and 6.25 mg for women and up to 12.5 mg for men for extended release tablets, both of which should be taken at bedtime, according to the Mayo Clinic.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

3. Access to healthcare

A Medicare CAHPS survey carried out in 2015 investigated how quickly patients accessed appointments and care, asking them to rate their experience out of 100. While these are self reported statistics, the difference between races was more than 10% in some cases. White women reported an average score of 73.9%, Black women 68.3%, API (Asian and Pacific Islander) women 63.1% and Hispanic women 69.1%. The survey included access to urgent care as well as appointments for checkups and routine care.

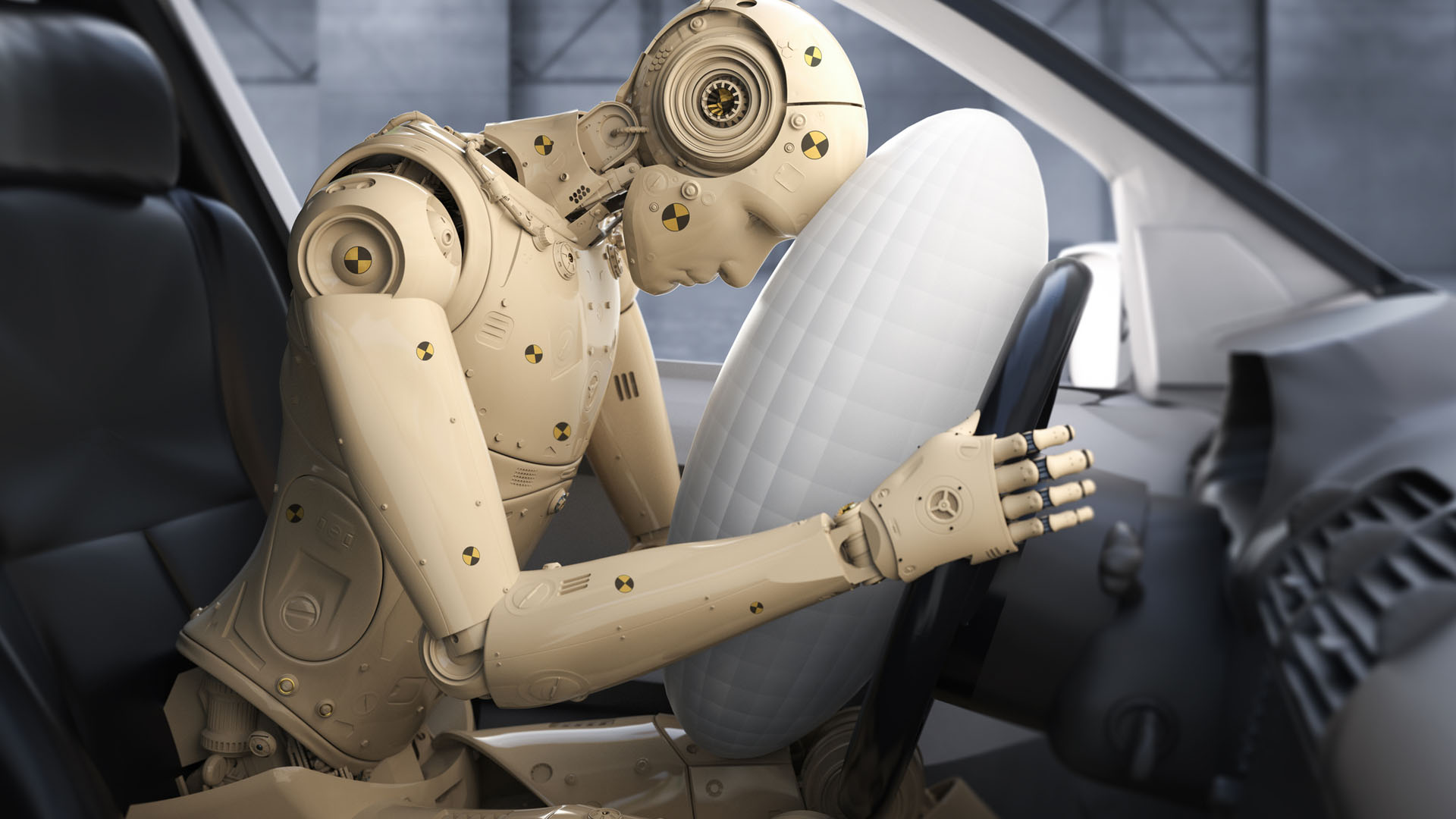

4. Crash test dummies

One disparity we're more aware of in modern times is that crash test dummies are based on a male body, which may contribute to higher female mortality from car accidents due to safety equipment not being tailored to women’s anatomy. According to a 2013 U.S. Department of Transportation report, women are 17% more likely than men to die in a car accident. A 2017 report in the journal Traffic Injury Prevention found that even when wearing a seatbelt, a woman's odds of getting seriously injured in a frontal collision are 73% higher than a man's in the same type of collision.

According to a 2019 review in the journal Accident Analysis and Prevention, there are still no legal requirements for governments to test with a variety of crash test dummies, and this is still the case. However, a bipartisan bill, The FAIR Crash Tests Act, was introduced in Nebraska in 2021 to investigate the lack of diversity in crash testing. In 2002, Volvo used computer modeling to test the impact of crashes on a woman in her 36th week of pregnancy, according to a Stanford case study, but the first female crash test dummy only debuted in 2022 in Sweden.

5. Maternal deaths

Research published in the American Journal of Public Health in 2021 analyzing maternal mortality rates in the U.S between 2016 and 2017 found that Black women are five times as likely to die from pregnancy-related cardiomyopathy (heart disease) and blood pressure disorders than white women. Obstetric hemorrhage (excessive blood loss during pregnancy) and obstetric embolism (blood clots during pregnancy) were also more likely to kill Black women than white women, with a 2.3% to 2.6% higher chance of death for Black women. Maternal death is classed as death during pregnancy and up to 42 days postpartum.

6. Representation in clinical trials

A 2017 report of global clinical trial participation published by the FDA found that women represent 43% of participants globally between 2015 and 2016. While this figure may sound relatively balanced, there is a caveat: A 2018 study in the British Journal of Pharmacology found that while this gender balance existed in the phase 2 and phase 3 trials, where women made up 48% and 49% of participants, respectively, in phase 1 trials, women represented only 22% of participants. In the reviewed phase 1 trials, even when the drugs being tested were designed to treat diseases more common in women than men, women were often poorly represented. For example, in trials of 10 different drugs, the study revealed a 20% gap between the number of women included in the trials and the prevalence of the disease amongst women in the general population.

7. Pain bias

According to a 2008 report in the journal Academic Emergency Medicine, women's pain is not as likely to be treated as men's — women were 13% to 25% less likely to receive opioids in the emergency room despite presenting with the same pain scores as men. A 2021 report in the Journal of Pain found that female patients were perceived to be in less pain than their male counterparts in a controlled experiment where participants viewed the facial expressions of women and men with acute shoulder pain.

8. The Thalidomide scandal

This particular example of the gender research gap from the 1950s changed the way medication was tested and how clinical trials were run thereafter. Thalidomide was a sedative that was often used for other purposes, including the treatment of colds and nausea in pregnancy, according to the Science Museum in London. It was developed in Germany and widely marketed in dozens of countries, but it was rejected by the FDA due to safety concerns.

Frequently used to treat morning sickness, the drug was widely used in pregnancy but later linked to serious birth defects. When Thalidomide was eventually taken off the market, an estimated 10,000 babies had been born with defects as a result of the drug, ranging from missing limbs to brain damage, according to the Thalidomide Trust.

It is now used as a treatment for inflammatory diseases such as HIV and cancer, according to a 2004 review published in The Lancet. It is prescribed with far more caution than in the past and never to pregnant women.

Drug testing changed as a result of the Thalidomide scandal — drug companies had to prove their drugs were suitable for pregnant women and drugs had to pass human trials before becoming available for public use, instead of going straight to market after the animal stage trial.

However, despite never being approved for use in pregnancy in the U.S. the “Shadows of Thalidomide” contributed to a lack of clinical trials involving pregnant women and women with potential to be pregnant, according to a 2022 article in Contemporary Clinical Trials.

9. Diabetes medicine: Troglitazone

In 2000, the diabetes medication Troglitazone was recalled by the FDA after it was linked to an increased risk of liver failure that mostly affected women. Around 67% of the reported cases of acute liver failure that were associated with troglitazone usage occurred in women, according to an article in the American Journal of Medicine. At least 24 cases of acute liver failure were reported before the drug was recalled, according to the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

Of the 89 acute cases studied by the American Journal of Medicine, 58 were women and only 11 recovered without liver transplantation. The organ damage progressed rapidly, with patients going from normal liver function to irreversible liver damage within the space of a month.

10. Drug-induced arrhythmia

Some people experience life-threatening ventricular arrhythmia — with the most common type, atrial fibrillation affecting 2% to 9% of people in the U.S. according the charity Arrhythmia Alliance — when taking a combination of certain drugs, including antihistamines, antibiotics, antimalarials and antiarrhythmics. Women are more than twice as likely than men to develop these drug-induced arrhythmias, according to a 2021 article in the journal Frontiers in Physiology.

Lou Mudge is a health writer based in Bath, United Kingdom for Future PLC. She holds an undergraduate degree in creative writing from Bath Spa University, and her work has appeared in Live Science, Tom's Guide, Fit & Well, Coach, T3, and Tech Radar, among others. She regularly writes about health and fitness-related topics such as air quality, gut health, diet and nutrition and the impacts these things have on our lives.

She has worked for the University of Bath on a chemistry research project and produced a short book in collaboration with the department of education at Bath Spa University.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus