Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

At the dark hearts of galaxies like the Milky Way lie supermassive black holes, with millions or even billions of times the sun's mass.

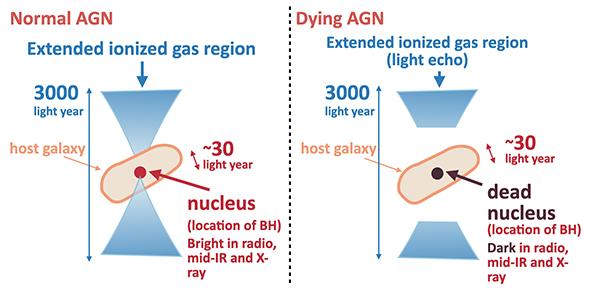

Some of those supermassive black holes are what scientists call active galactic nuclei (AGN), which spew out copious amounts of radiation like X-rays and radio waves. AGN are responsible for the twin jets of ionized gas you see shooting away in pictures of many galaxies.

As all things must pass, so too must every AGN one day shut off. But scientists have never quite understood how or when that happens. Now, researchers led by Kohei Ichikawa, an astronomer at Tohoku University in Sendai, Japan, may have found a clue. Looking at the distant galaxy Arp 187, those researchers have seen what they think is an AGN in its very last days.

Related: Black holes of the universe (images)

Ichikawa and his colleagues observed Arp 187 with the radio telescopes at the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in northern Chile and the Very Large Array (VLA) in New Mexico. They spotted twin jet lobes, a telltale sign of an AGN. But they couldn't detect radio waves, which also should have been coming from an active nucleus.

So, the researchers took a second look at Arp 187's core with NASA's NuSTAR ("Nuclear Spectroscopic Telescope Array") X-ray satellite. AGN normally produce X-rays in abundance, but no such signal emerges in the NuSTAR data, the team reported in a study presented earlier this month at the 238th meeting of the American Astronomical Society, which was held virtually.

The researchers therefore think that, sometime in the past several thousand years (as observed from Earth), Arp 187's AGN has gone dark.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This observation is possible because an AGN's jets are colossal. Arp 187's stretch out for 3,000 light-years, meaning that you can see their matter stream away for millennia after the AGN core "dies." Astronomers call this mourning period a "light echo." It's like watching smoke from a newly extinguished fire.

The researchers have called their discovery "serendipitous." Arp 187 could be a stepping stone to learning more about what happens at the end of an AGN's life, study team members said.

"We will search for more dying AGN using a similar method as this study," Ichikawa said in a statement. "We will also obtain the high spatial resolution follow-up observations to investigate the gas inflows and outflows, which might clarify how the shutdown of AGN activity has occurred."

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Rao is a freelance science journalist based in New York and is a contributor to Live Science’s sister site Space.com, as well as Popular Science, EEE Spectrum and Gizmodo. Rao has a bachelor’s degree in Physics and English from Vanderbilt University, and a master’s degree in Science, Health and Environmental Reporting from New York University.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus