Hundreds of three-eyed 'dinosaur shrimp' emerge after Arizona monsoon

Their eggs can stay dormant for decades, waiting for water.

Following a torrential summer downpour in northern Arizona, hundreds of bizarre, prehistoric-looking critters emerged from tiny eggs and began swimming around a temporary lake on the desert landscape, according to officials at Wupatki National Monument.

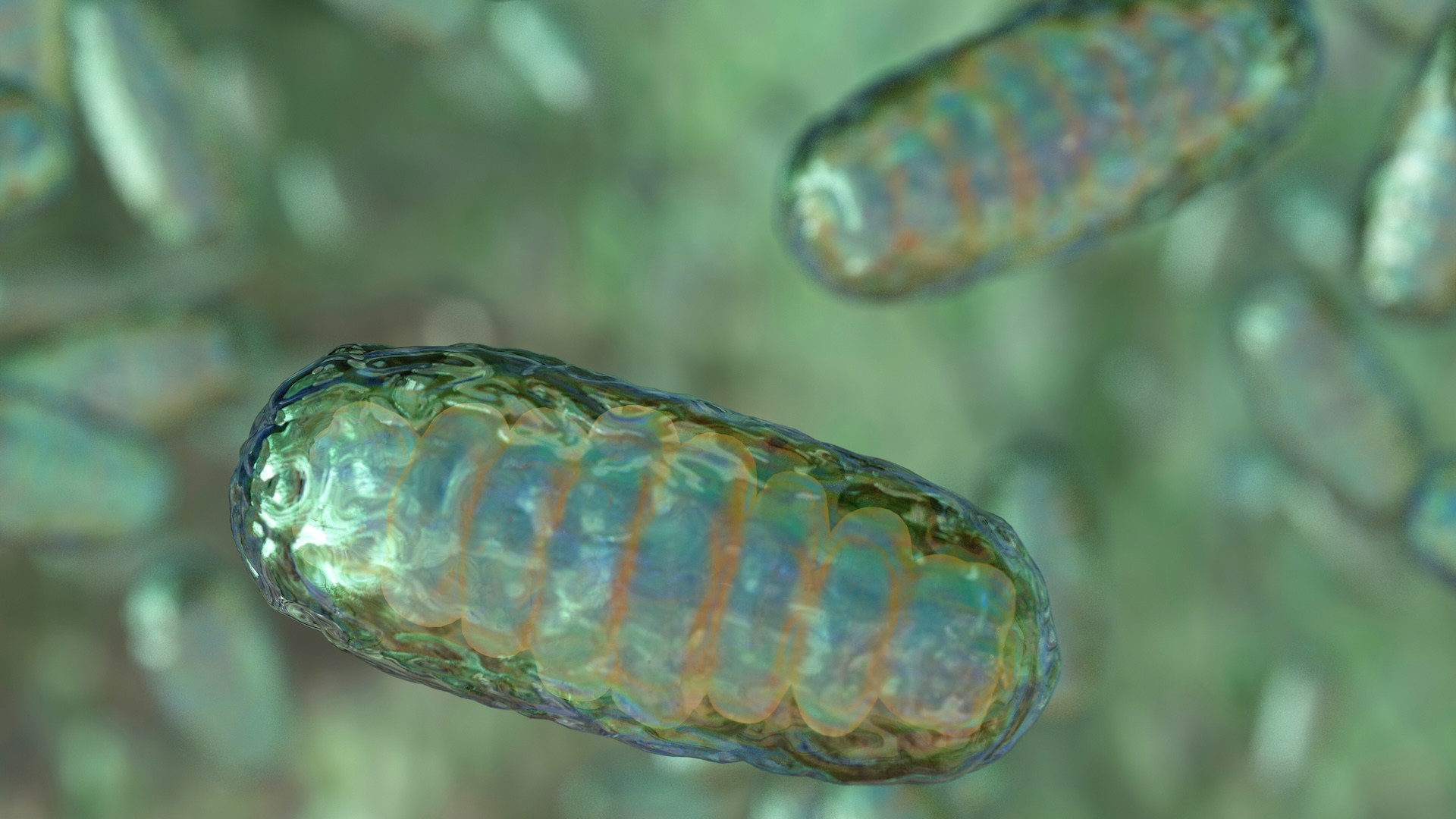

These tadpole-size creatures, called Triops "look like little mini-horseshoe crabs with three eyes," Lauren Carter, lead interpretation ranger at Wupatki National Monument, told Live Science. Their eggs can lie dormant for decades in the desert until enough rainfall falls to create lakes that provide real estate and time for the hatchlings to mature and lay eggs for the next generation, according to Central Michigan University.

Triops' appearances are so uncommon, that when tourists reported seeing them at a temporary, rain-filled lake within the monument's ceremonial ball court — a circular walled structure 105 feet (32 meters) across — the monument's staff weren't sure what to make of the critters.

Related: Photos: Ancient sea monster was one of largest arthropods

Following a monsoon in late July, "We knew that there was water in the ball court, but we weren't expecting anything living in it," Carter said. "Then a visitor came up and said, 'Hey, you have tadpoles down in your ballcourt.'"

At first, Carter wondered if toads, which live in underground burrows during the dry season, had emerged during the wet spell to lay eggs. To investigate, she went to the ballcourt, which was originally built by the Indigenous people at Wupatki.

"I just scooped it up with my hand and looked at it and was like 'What is that?' I had no idea," Carter said. But then, she felt an inkling of familiarity; Carter had previously worked at Petrified Forest National Park in northeastern Arizona, and recalled reports of Triops there. "And then I had to look it up," she said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Three-eyed crustacean

Triops — which is Greek for "three eyes" — are sometimes called "dinosaur shrimp" because of their long evolutionary history; the ancestors of these crustaceans evolved during the Devonian period (419 million to 359 million years ago), and their appearance has changed very little since then, according to Central Michigan University. (Of note, the dinosaurs didn't emerge until much later, during the Triassic period, which began about 252 million years ago.)

However, Triops aren't exactly the same as their ancestors, so they wouldn’t be considered "living fossils."

"I don't like the term 'living fossil' because it causes a misunderstanding with the public that they haven't changed at all," Carter said. "But they have changed, they have evolved. It's just that the outward appearance of them is very similar to what they were millions of years ago."

There are two genuses in the family Triopsidae — Triops and Lepidurus — that together include up to 12 species, Central Michigan University reported. The critters found at the Wupatki ball court could be Triops longicaudatus, a species found in short-lived freshwater ponds, known as vernal pools, in North, Central and South America, but a scientific analysis is needed to confirm it, Carter said.

After hatching, Triops can grow up to 1.5 inches (4 centimeters) long, with a shield-like carapace that looks like a miniature helmet, according to Central Michigan University. Their eyes make them look angry and wise at the same time — they have two large, black-rimmed compound eyes (like those of a dragonfly or bee) and a small ocellus, or simple eye, between them. Ocellus eyes are common among arthropods (a group that includes insects, crustaceans and arachnids), which are filled with simple photoreceptors that help these creatures detect light, according to the Amateur Entomologists' Society.

Related: Photos: Ancient shrimp-like critter was tiny but fierce

In this case, the Triops at Wupatki National Monument got lucky with a short but intense rainy spell. Usually, Wupatki gets around 9 inches (22.9 cm) of rain a year, Carter said. In 2020, Wupatki had its driest lowest monsoon summer on record, with just 4 inches (10.2 cm) of rain, Carter said. But in the last week and a half of July 2021, the region got a tumult of rain: nearly 5 inches (12.7 cm).

During that time, the Triops' eggs hatched and, within hours, the little critters likely began filter feeding, according to a life cycle description at Central Michigan University. Like other crustaceans, they went through several molts before fully maturing in just over a week.

Triops males and females typically pair up to mate by sexual reproduction, but in times of scarcity, they have other means; these crustaceans are also hermaphrodites, meaning they have both male and female sex organs, and parthenogenetic, meaning females can produce offspring from unfertilized eggs, according to BioKids, a partnership between the University of Michigan School of Education, University of Michigan Museum of Zoology and the Detroit Public Schools.

Triops can live up to 90 days, but the pond at the ball court lasted just three to four weeks, Carter said. Almost immediately, local birds took notice, with ravens and common nighthawks swooping down into the water to gobble up the critters, she noted.

It's unknown how many Triops managed to lay eggs before the lake dried up. Rangers will have to wait for the next monsoon to find out.

Editor's note: This story was corrected at 2:22 p.m. EDT to note that Triops means "three eyes" in Greek, not Latin, as was previously stated. It was updated at 9:32 a.m. EDT Oct. 6 to clarify that the rainfall measurements were for Wupatki, not Flagstaff, Arizona.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.