Crested rats can kill with their poisonous fur

The African crested rat's fur packs a lethal punch.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

African crested rats are rabbit-size fuzzballs with endearing faces and a catlike purr. But they're also highly poisonous, their fur loaded with a toxin so powerful that just a few milligrams is deadly enough to kill a human.

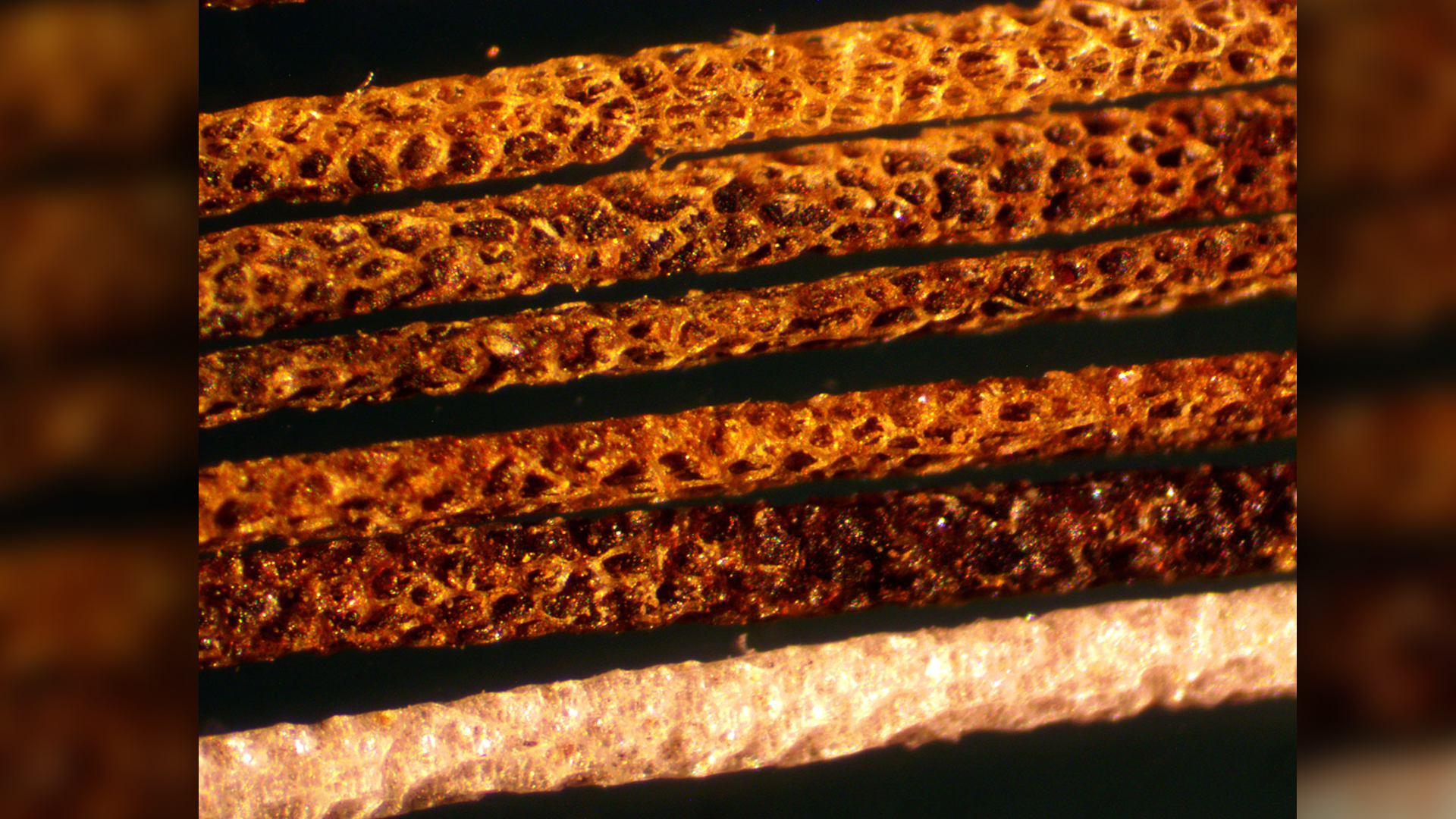

The rats don't produce the poison themselves. Rather, they borrow it from a poisonous plant by chewing on the bark, mixing the toxin with their saliva and then grooming the lethal liquid into stripes of specialized hairs on their flanks, a new study shows.

Some mammal species, such as shrews, moles and vampire bats, possess a toxic saliva, while slow lorises — the only venomous primate — homebrew their venom by mixing saliva with a secretion from their armpits. But the crested rat (Lophiomys imhausi) is the only mammal to derive its poison protection directly from plants.

Related: Photos: The poisonous creatures of the North American deserts

Crested rats' bodies measure about 9 to 14 inches (225 to 360 millimeters) long, and they inhabit woodlands in Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia, Sudan, Tanzania and Uganda, according to Animal Diversity Web (ADW), a biodiversity database maintained by the University of Michigan's Museum of Zoology. The rats were first described in 1867 and were long suspected of being poisonous. But they were so difficult to trap or observe that little was known about their habits — or where their poison came from, researchers reported Nov. 17 in the Journal of Mammalogy.

In 2011, biologists proposed that the rats extracted their poison by chewing bark from the poison arrow tree (Acokanthera schimperi) and then applied the toxic substance by licking specialized hairs that the rodents display when threatened. This tree bark contains cardenolides — compounds that are also found in foxglove (Digitalis purpurea) and which are highly toxic to most mammals. Very small doses of cardenolides are used in heart medications such as digitalis to correct arrhythmia, but higher quantities can cause vomiting, convulsions, breathing difficulties and cardiac arrest. Oral contact with the rats' poison-slicked hairs can be fatal, and dogs have died after attacking crested rats, the scientists wrote.

But the 2011 investigation described bark-chewing and fur-licking in just one rat, so researchers didn't know how widespread this behavior was in the species, Denise Dearing, co-author of the new study and a Distinguished Professor of Biological Sciences at the University of Utah, said in a statement.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For the new study, the researchers captured 25 rats in Kenya and temporarily kept them in captivity, installing cameras in the animals' enclosures and analyzing nearly 1,000 hours of footage of rat behavior: 447 daytime hours and 525 hours at night. They observed 10 rats that chewed the bark from A. schimperi, applied toxin-loaded spit to their fur and didn't seem affected by the poison, according to the study. Crested rats have "an unusual four-chambered stomach with a dense bacterial community," so it's possible that gut microbes break up cardenolides and prevent the toxins from sickening the rats, the study authors reported.

These toxins — and the rats' warning coloration — are likely most effective against predators that attack by biting, such as hyenas, jackals and leopards, said lead study author Sara Weinstein, a Smithsonian-Mpala Postdoctoral Fellow with the Smithsonian Institution and the University of Utah.

"The rats' defense system is probably much less effective against a predator that attacks from above and can avoid the poisonous hairs on the rat's sides by grabbing with talons," Weinstein told Live Science in an email.

The scientists were also surprised to learn that the rats — thought to be solitary — lived monogamously in male-female pairs, spending more than 50% of their time together and communicating with a range of sounds that included squeaks and purrs. However, toxin application was not a shared activity, Weinstein explained.

"We only ever observed rats anointing themselves, even when in pairs," she said. "More behavioral studies, particularly looking at sequestration in very young rats, could be very interesting."

As the crested rat is rarely glimpsed in the wild, scientists are still uncertain about the rats' population numbers and conservation status. But with humans increasingly invading and reshaping the rats' forest homes, risks to the animals have grown over the past decade, said Bernard Agwanda, Curator of Mammals at the Museums of Kenya, and co-author of this study and of the 2011 paper.

"We are looking at a broad range of questions influenced by habitat change," he explained. "We need to understand how that impacts their survival."

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus