Polio is spreading in the US for the 1st time in decades. Do you need a booster?

A case of paralytic polio has been detected in the U.S.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A specific type of poliovirus has been spreading in Rockland County, New York, as well as in neighboring areas, prompting the World Health Organization (WHO) to add the United States to a list of countries where similar polioviruses have been detected. The list includes about 30 countries in Europe, Asia and Africa, such as the United Kingdom, Israel, Yemen, Algeria and Niger.

The official addition of the U.S. to this list was announced last week by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the news raised questions about what happens next. Do people who received all of their polio vaccine doses as children now need a booster? What should you do if you're uncertain of your vaccination status, or if you know for sure that you have not received the polio vaccine?

Crucially, there's no sweeping recommendation for fully vaccinated people to seek polio boosters.

"Certainly, at the moment, there haven't been any national or local recommendations for people who are secure about their childhood vaccination series to need an additional booster," said Dr. William Schaffner, a professor of medicine in the division of infectious diseases at the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine in Tennessee. However, he noted that there may be select circumstances — which we'll detail below — in which it might be reasonable for an individual to seek a booster.

Related: Who created the polio vaccine?

For now, health officials' primary concern is vaccinating those who haven't yet completed their polio vaccination series, Schaffner told Live Science.

"Polio vaccination is the safest and best way to fight this debilitating disease and it is imperative that people in these communities who are unvaccinated get up to date on polio vaccination right away," Dr. José R. Romero, director of the CDC's National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, said in the CDC statement. "We cannot emphasize enough that polio is a dangerous disease for which there is no cure."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Baseline polio vaccine recommendations

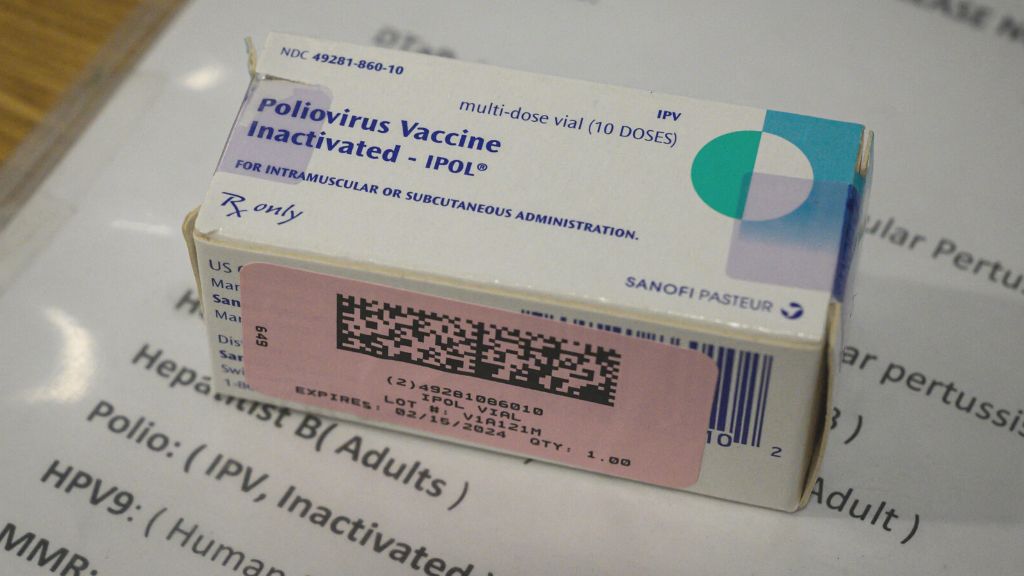

Since 2000, the U.S. has only used the inactivated polio vaccine (IPV), a shot that's typically injected into the arm or leg and contains a "dead" poliovirus that cannot cause disease, according to the CDC. Another kind of polio vaccine, the oral polio vaccine (OPV), is similarly effective, but its use was halted in the U.S. because it contains live, but weakened, poliovirus, Live Science previously reported. These weakened viruses can be shed in the stool of vaccinated people and, in rare instances, can evolve to behave like wild, naturally occurring polioviruses capable of causing illness and potentially paralysis in unvaccinated people.

Due to this risk, the U.S. now only administers the IPV, but "vaccine-derived" polioviruses can still potentially be imported from places that use the OPV — and that's exactly what happened in the current outbreak.

"It reveals how vulnerable we are to importations — not only of polioviruses, but of other viruses, germs, from abroad," Schaffner said.

To guard against polio, the CDC recommends U.S. children get four doses of the IPV, with one dose given at each of the following ages: 2 months old, 4 months old, between 6 and 18 months old, and between 4 and 6 years old. The CDC also offers several "catch-up schedules" for children who start their vaccination series late or get delayed between doses.

Adults who have never received a polio vaccine should get three doses of the IPV. These individuals can get their first dose anytime, receive the second dose one to two months later, and get the third dose six to 12 months after that, the CDC recommends. Adults who received only one or two doses in the past should seek additional doses, to reach the recommended three.

Most U.S. residents complete their polio vaccine series in childhood and aren't generally recommended to get boosters later in life. "This is just a testimony to the very solid, lifelong protection you get from the polio vaccine," Schaffner said.

The first polio vaccines became available in 1955 and the shots have been recommended as routine vaccinations since then, according to Verify. An adult is considered fully vaccinated if they've gotten at least three doses of either the IPV or the "trivalent" OPV (tOPV), meaning the OPV that guards against all three types of poliovirus, P1, P2 and P3. Alternatively, an adult is fully vaccinated if they've gotten four doses of any combination of the IPV and the tOPV, according to the CDC.

Two doses of the IPV are at least 90% protective against paralytic polio, which can occur when the virus infiltrates the central nervous system and causes weakness or paralysis in the arms, legs or both; this can lead to permanent disability and death. Three doses are at least 99% protective, according to the CDC.

Related: Africa declared free of wild poliovirus

Who needs a polio booster?

There are instances in which fully vaccinated adults may consider a one-time polio booster.

For example, a booster would be recommended if you work in a lab or health care setting where you handle poliovirus specimens, or if you are a health care worker who treats patients with polio or may interact with the close contacts of people infected with the virus. You may also seek a booster if you're traveling to a country where the risk of polio exposure is "greater." For example, wild poliovirus still circulates in Afghanistan and Pakistan, and long-term visitors should get an IPV booster between four weeks and one year prior to traveling there, according to the Global Polio Eradication Initiative. (No similar recommendations have been extended to the U.S. yet.)

So far, only one case of paralytic polio has been detected in the U.S. outbreak; this occurred in an unvaccinated adult in Rockland County. Subsequently, poliovirus was detected in wastewater samples from Rockland County, Orange County, Sullivan County, New York City and Nassau County, the New York State Department of Health reported.

The health department currently recommends polio boosters for the following New Yorkers:

- Individuals who will or might have close contact with a person known or suspected to be infected with poliovirus or such person's household members or other close contacts.

- Health care providers who work in areas where poliovirus has been detected and might handle specimens that might contain polioviruses or who treat patients who might have polio.

- Individuals with occupational exposure to wastewater.

People in the affected counties who have weakened immune systems might also consider a booster, Vincent Racaniello, a poliovirus expert at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, said in a statement. And if you're unsure of how many polio vaccine doses you've received, you may also consider getting boosted, he said.

There are some antibody tests for polio, but these aren't recommended for assessing vaccination status because there's limited access to tests that screen for antibodies against all three types of poliovirus, according to a 2017 Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report published by the CDC. "In the absence of the availability of testing for antibodies to all 3 serotypes, serologic testing is no longer recommended to assess immunity," the report states.

For U.S. residents beyond New York, the risk of polio exposure is likely similar to before the outbreak, Schaffner said — that is, negligible. However, people exposed to the virus in New York could potentially hop on a plane and carry polio to additional places; for that reason, vaccination remains important no matter where you live, he said.

It's also key to note that "while IPV is very good at preventing the most severe potential effects of the disease, people who received the vaccine could still be carriers of polio and could transmit it to others," Dr. Leana Wen, an emergency physician and professor of health policy and management at The George Washington University Milken Institute School of Public Health, told CNN.

Those vaccinated with the IPV can still pass poliovirus in their stool if they're ever exposed to the pathogen, even though they are protected against paralysis, according to the Pan American Health Organization. That's because the IPV generates a very strong antibody response in the blood but isn't as effective at generating immunity in the intestines.

About polio

Poliovirus most often spreads through contact with the feces of an infected person; less commonly, it can be transmitted through respiratory droplets that are released when an infected person sneezes or coughs, according to the CDC. Frequent handwashing with soap and water can help prevent the spread of the virus; notably, however, alcohol-based hand sanitizers do not kill polioviruses.

Most people who catch polio don't develop any visible symptoms. About 25% develop flu-like symptoms, including sore throat, fever, fatigue, stomach pain and nausea. A far smaller fraction of infected people develop severe symptoms, such as meningitis, an infection of the tissue surrounding the spinal cord and/or brain; or paralysis, which can lead to permanent disability and death.

Sometimes, people who seem to recover from polio develop new muscle pain, weakness or paralysis decades later; this is known as post-polio syndrome.

Originally published on Live Science.

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus