Book of the Dead fragments, half a world apart, are pieced together

A piece in New Zealand matched one in Los Angeles.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

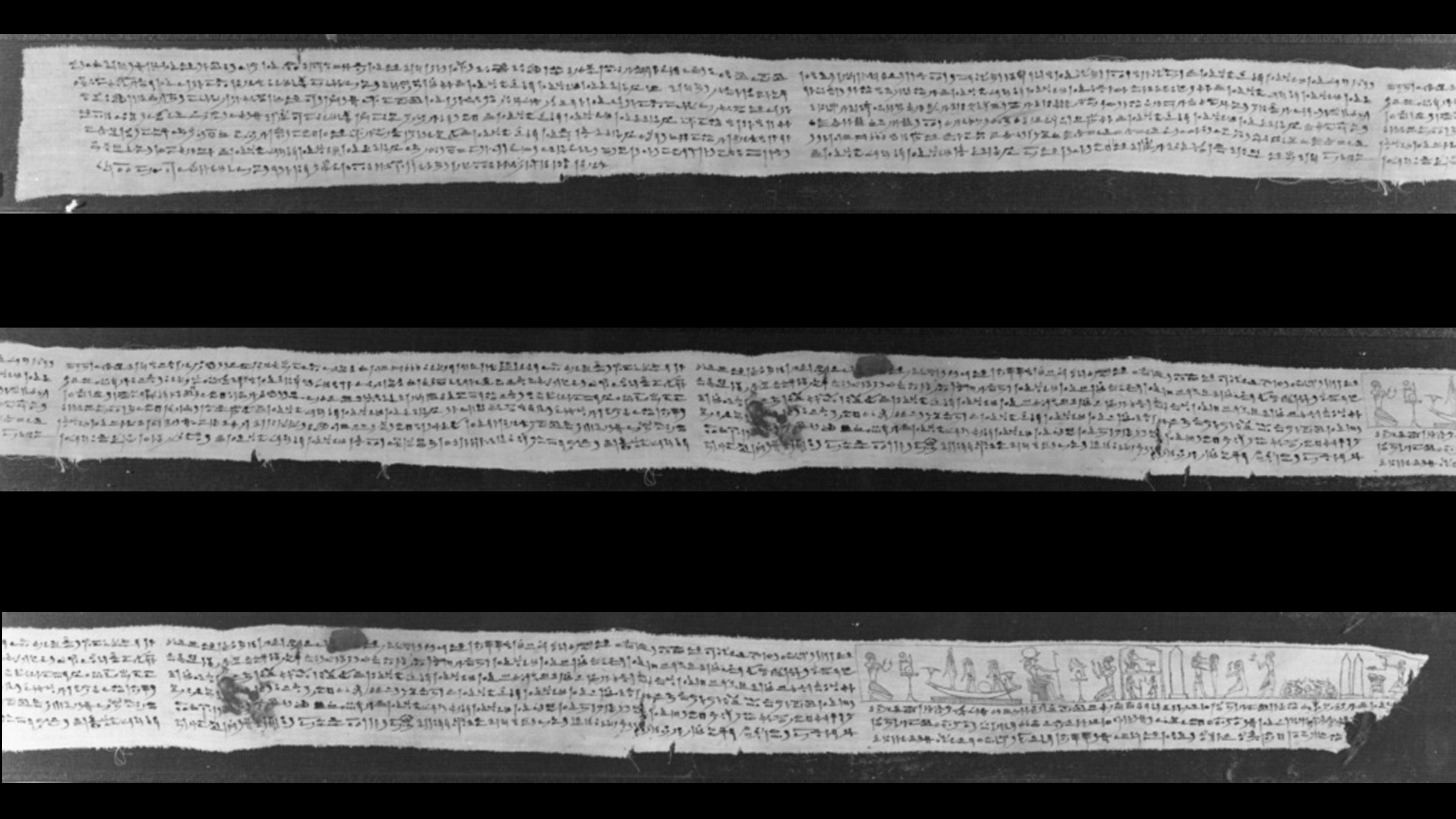

A torn 2,300-year-old mummy wrapping — covered with hieroglyphics from the ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead — has been digitally reunited with its long-lost piece that was ripped away.

The two linen fragments were pieced together after a digital image of one segment was cataloged on an open-source online database by the Teece Museum of Classical Antiquities at the University of Canterbury in New Zealand. Historians at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles who saw the image quickly realized that the institute had a shroud fragment that, like a puzzle piece, fit together with the New Zealand segment.

"There is a small gap between the two fragments; however, the scene makes sense, the incantation makes sense and the text makes it spot-on," Alison Griffith, an Egyptian art expert and an associate professor of classics at the University of Canterbury, said in a statement. "It is just amazing to piece fragments together remotely."

Related: In photos: Egypt's oldest mummy wrappings

Both fragments are covered with hieratic, or cursive, script, as well as hieroglyphics that depict scenes and spells from the Book of the Dead, an ancient Egyptian manuscript thought to guide the deceased through the afterlife.

"Egyptian belief was that the deceased needed worldly things on their journey to and in the afterlife, so the art in pyramids and tombs is not art as such; it's really about scenes of offerings, supplies, servants and other things you need on the other side," Griffith said.

Versions of the Book of the Dead varied from tomb to tomb, but one of the book's most famous images is the weighing of the deceased's heart against a feather, according to the American Research Center in Egypt (ARCE), which was not involved with the new finding. The tradition of including the "Book of the Dead" in burials began with inscriptions, known as the Pyramid Texts, written directly on tomb walls during the late Old Kingdom, and was initially offered only to royalty buried at Saqqara. The earliest known Pyramid Text was found in the tomb of Unas (who lived from around 2465 B.C. to 2325 B.C.), the last king of the Fifth Dynasty, according to Encyclopedia Britannica.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, as beliefs and religious practices changed, Egyptians began including adapted versions, known as the Coffin Texts, that were written on the coffins of nonroyal people, including wealthy elites, according to ARCE. By the time of the New Kingdom (around 1539 B.C.), the afterlife was thought to be accessible to all who could afford their own Book of the Dead, and was written on papyrus and linens that were wrapped around mummified bodies, according to ARCE and the University of Canterbury statement.

Writing on these mummy wrappings, however, was no easy feat.

"It is hard to write on material; you need a quill and a steady hand, and this person has done an amazing job," Griffith said of the linen fragment at Canterbury. Its illustrations show afterlife preparation scenes: butchers cutting an ox for an offering; men moving furniture for the afterlife; four bearers with nome (territorial divisions in Egypt) identifiers, including a hawk, ibis and jackal; a funerary boat with the goddess sisters Isis and Nephthys on either side; and a man pulling a sledge with the image of Anubis, the jackal-headed god of the dead, according to the statement. Some of these scenes are also present in the famous "Book of the Dead" version on the Turin Papyrus, currently housed in the Egyptian Museum in Turin, Italy.

While the Canterbury linen fragment is long, especially once it was (digitally) joined with the fragment from the Getty Museum, it was just one of many that were used to wrap the body of a mummified man.

"Your linen fragment is just one small piece of a set of bandages that were torn away from the remains of a man named Petosiris (whose mother was Tetosiris)," Foy Scalf, head of research archives at the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago, said in the statement. "Fragments of these pieces are now spread around the world, in both institutional and private collections.

"It is an unfortunate fate for Petosiris, who took such care and expense for his burial," Scalf continued. "And, of course, it raises all sorts of ethical issues about the origins of these collections and our continued collecting practices."

The history of artifact acquisition is now under greater scrutiny than in prior years, with increased interest in how pieces were collected, sold and moved around the world. In fact, tracking down separated artifacts that were previously joined is now a subfield of museum studies, Griffith said. She noted the provenance of the fragment at the University of Canterbury: It came into the hands of Charles Augustus Murray, who was British consul general in Egypt from 1846 to 1853, and later became part of the collection of Sir Thomas Phillips, a senior British civil service member. Then, it was bought on behalf of the university at a Sotheby's sale in London in 1972.

But it's a mystery how the Canterbury and Getty fragments became separated, Griffith said.

Editor's Note: This article was updated at 2:32 p.m. EDT Aug. 10 to change Getty Research Institute to Getty Museum.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus