Twin black holes caught chowing down on the leftovers of a galaxy merger

Binary black holes may be more common than astronomers realized, according to new research.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Two black holes have been found munching matter side by side at the heart of two merging galaxies, suggesting that binary black holes may be more common than scientists thought.

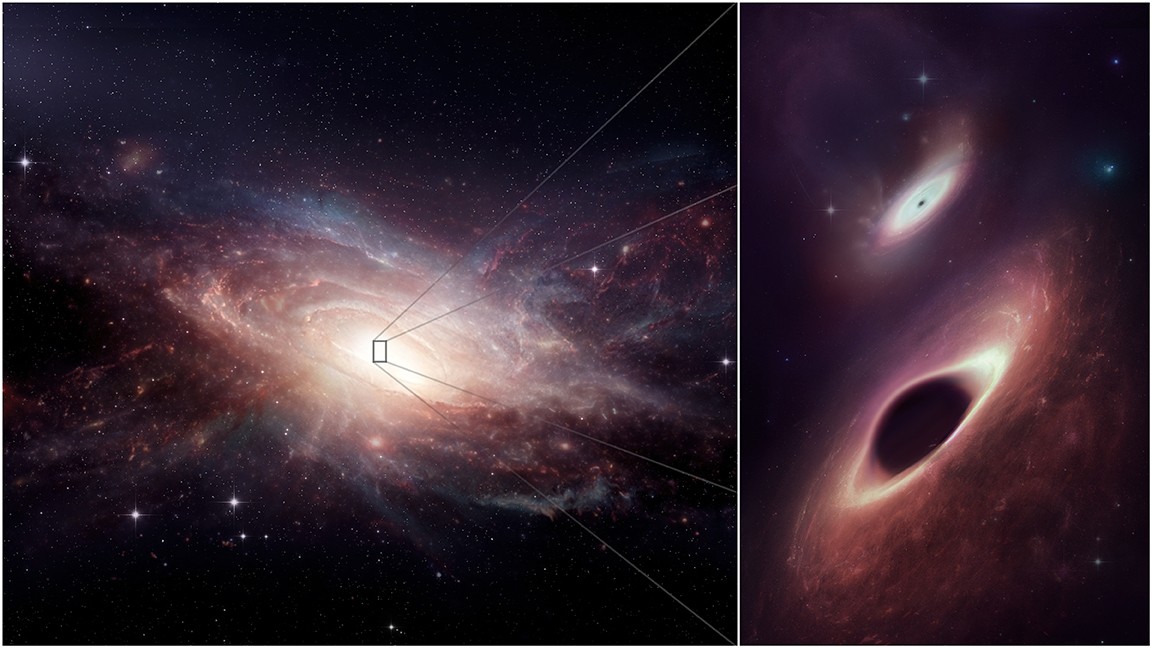

Researchers reported the finding Jan. 9 in The Astrophysical Journal Letters and at the 241st meeting of the American Astronomical Society, held in Seattle. They found the destructive duo in UGC 4211, a galaxy 500 million light-years away in the constellation Cancer, which is the result of two separate galaxies merging. UGC 4211 is in the last stages of this merger; one day, our own Milky Way galaxy will undergo a similar collision with the nearby Andromeda galaxy.

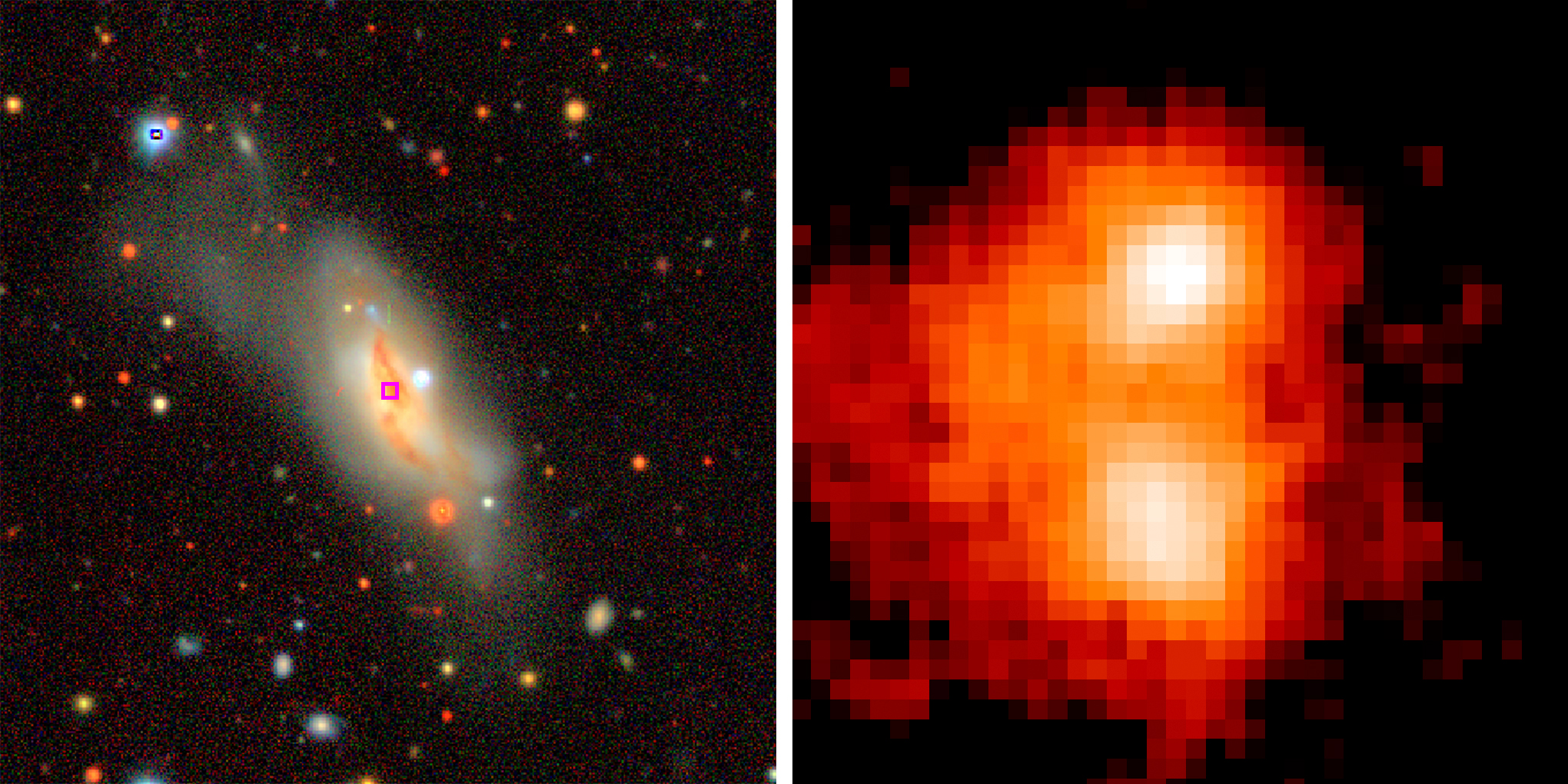

Using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), a telescope array capable of peering past clouds of dust and gas into the hearts of far-flung galaxies, researchers found that this galaxy is anchored at its center by not one, but two supermassive black holes. They sit only 750 light-years apart and are actively pulling in, or accreting, material and growing.

"Our study has identified one of the closest pairs of black holes in a galaxy merger, and because we know that galaxy mergers are much more common in the distant Universe, these black hole binaries too may be much more common than previously thought," study lead author Michael Koss, a senior research scientist at Eureka Scientific, said in a statement.

The findings have implications for what astronomers can expect to find as they probe the universe for gravitational waves, ripples in space-time caused by dramatic processes such as black holes colliding with one another.

"There might be many pairs of growing supermassive black holes in the centers of galaxies that we have not been able to identify so far," study co-author Ezequiel Treister, an astronomer at the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile, said in the statement. "If this is the case, in the near future we will be observing frequent gravitational wave events caused by the mergers of these objects across the Universe."

Galaxy mergers are often observed, especially in the distant universe, far from the Milky Way. Getting a good look at these events isn't easy because of the distances involved and the dusty, gassy debris between Earth and the luminous centers of these far-flung galaxies.

The researchers combined observations from the Chandra X-ray Observatory, the Hubble Space Telescope, the Very Large Telescope in Chile, and the Keck Observatory in Hawaii, all of which provided data in different wavelengths, allowing for a detailed look at the merged galaxy.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Each wavelength tells a different part of the story," Treister said. "While ground-based optical imaging showed us the whole merging galaxy, Hubble showed us the nuclear regions at high resolutions. X-ray observations revealed that there was at least one active galactic nucleus in the system. And ALMA showed us the exact location of these two growing, hungry supermassive black holes."

The experience of UGC 4211 may provide a glimpse into the Milky Way's own future.

"The Milky Way-Andromeda collision is in its very early stages and is predicted to occur in about 4.5 billion years," Koss said. "What we've just studied is a source in the very final stage of collision, so what we're seeing presages that merger and also gives us insight into the connection between black holes merging and growing and eventually producing gravitational waves."

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus