Bizarre aye-ayes use spooky, bony finger for nose picking

A new study in aye-ayes is the first to review nose picking in primates and reports the first evidence of the habit in lemurs.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

You can't pick your primate relatives, but your primate relatives can pick their noses. And they enjoy the taste of what they find, researchers recently learned.

One of those primates — aye-ayes, which are wild-haired and pop-eyed nocturnal lemurs that live only in Madagascar — are especially adept at nose picking. They have long, bony fingers; one of these is exceptionally long, and the aye-ayes typically use it for tapping on hollow branches to locate delicious grubs to eat. But they also use this peculiar-looking skeletal digit for excavating other tasty treats: ropy lengths of snot from deep inside their noses.

If you're curious about nose picking, you probably don't have to look very far to find examples of this behavior; it's commonly practiced by humans of all ages, as well as other primate species. But despite being frequent and widespread, nose picking is "poorly studied," scientists reported Oct. 26 in the Journal of Zoology.

So they decided to probe a little deeper into the subject.

Related: Secrets of a strange lemur: An aye-aye gallery

Their study offers the first review of nose picking across primates, identifying it in at least 12 species and including the first evidence of the habit in lemurs. Aye-ayes (Daubentonia madagascariensis) are a type of lemur with hands that are so bizarre that scientists previously said the animals looked like they were "walking on spiders." One finger, in particular, is especially lengthy and skinny, making it just the right size and shape for inserting deep into an aye-aye's nasal cavity to extract what lies within.

In fact, that finger is so long and flexible that an aye-aye can insert "the entire length of its extra-long, skinny and highly mobile middle finger into the nasal passages" and reach all the way into its pharynx, the cavity that lies behind the nose and mouth and connects them to the esophagus. After withdrawing this questing digit, the aye-aye then "licks the nasal mucus collected," a practice known as mucophagy, the study authors reported.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To see how many primates were confirmed nose pickers, the scientists dug into published studies, scanning for mentions of terms such as "nose picking," "nose picking primates," "nose picking evolution," "mucophagy" and "rhinotillexis" (a fancy word for nose picking). They found examples in 11 species that spanned four primate families and included great apes and both Old World and New World monkeys.

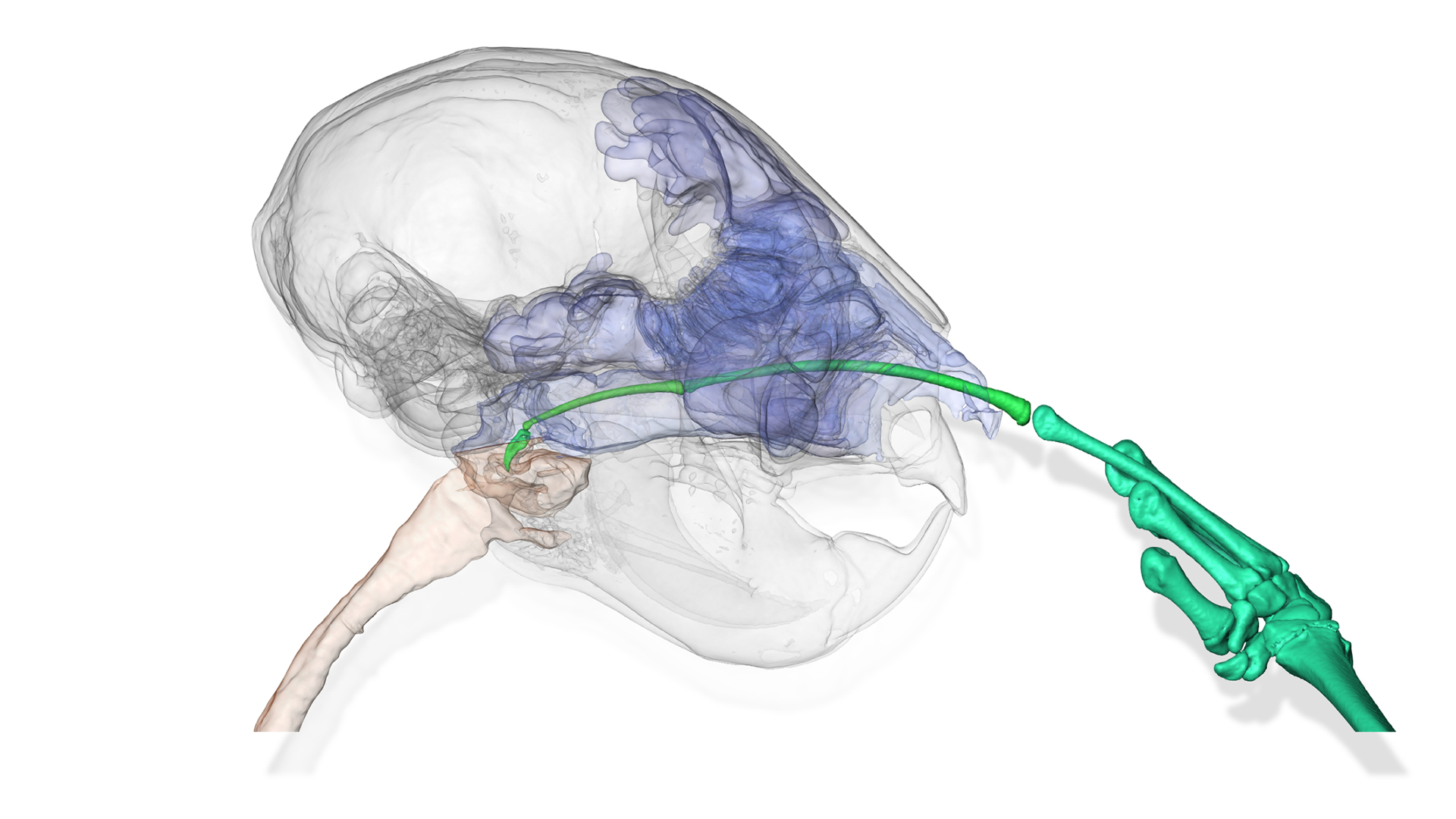

Video footage of an aye-aye at the Duke Lemur Center in Durham, North Carolina — a female named Kali — showed the cat-size primate "using its thin and elongated middle finger to pick its nose and then licking the nasal mucus," according to the study. To find out how deep that finger could go inside an aye-aye's nasal passage, the researchers obtained a CT scan of an aye-aye's head and then created a digital visualization of the nose picking, using the video footage for reference. Based on the reconstructed interaction between the skull and the hand, they determined that Kali's finger likely descended into her oral cavity.

"This video brings the number of species known to pick their nose to twelve," the scientists reported.

As to why humans, aye-ayes and other assorted primates pick their noses and sample what they find, "there is no scientific consensus about the potential costs or benefits of this behaviour," the study authors wrote. But who can say what secrets about nose picking in primates have yet to be extracted, if scientists would only dig deep enough?

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus