'Last Ice Area' in the Arctic may not survive climate change

Even the thickest, oldest Arctic sea ice is disappearing as Earth heats up.

The "Last Ice Area," an Arctic region known for its thick ice cover, may be more vulnerable to climate change than scientists suspected, a new study has found.

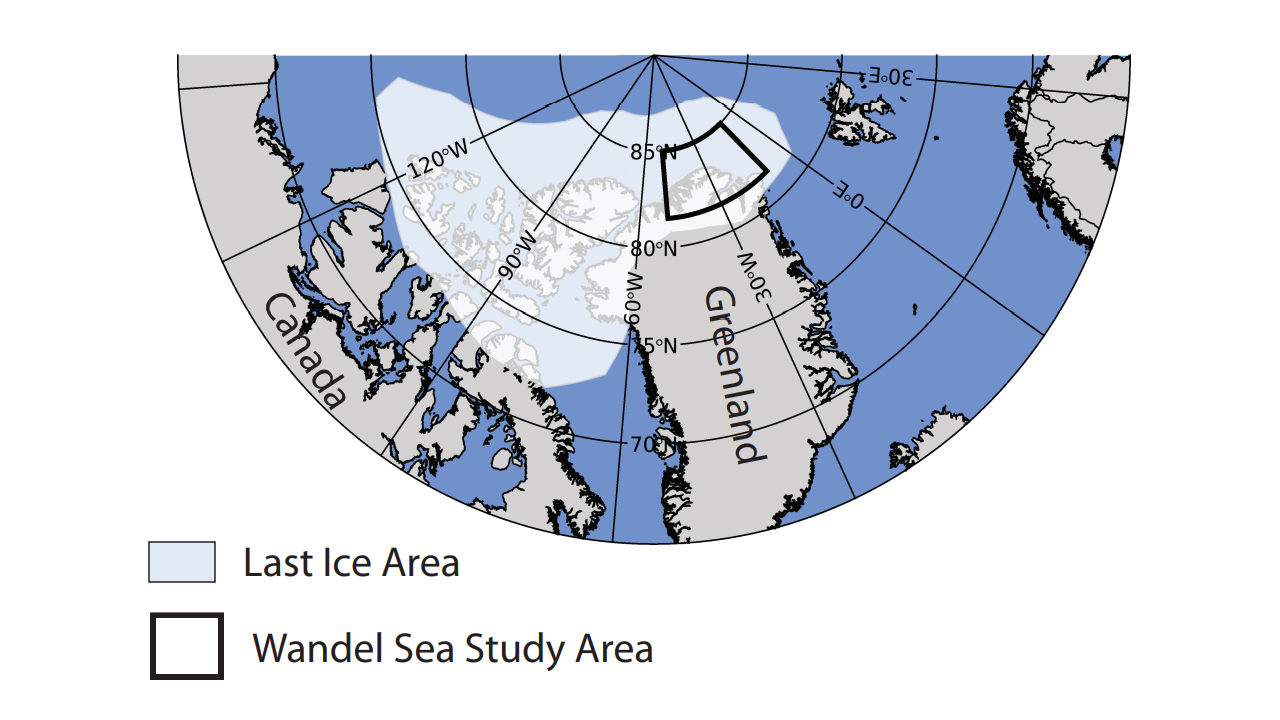

This frozen zone, which lies to the north of Greenland, earned its dramatic name because even though its ice grows and shrinks seasonally, much of the sea ice here was thought to be thick enough to persist through summer's warmth.

But during the summer of 2020, the Wandel Sea in the eastern part of the Last Ice Area lost 50% of its overlying ice, bringing coverage there to its lowest since record-keeping began. In the new study, researchers found that weather conditions were driving the decline, but climate change made that possible by gradually thinning the area's long-standing ice year after year. This hints that global warming may threaten the region more than prior climate models suggested.

Related: Images of melt: Earth's vanishing ice

As climate change melts other regions of the Arctic, that could spell trouble for the animals that depend on sea ice for breeding, hunting and foraging, as the Last Ice Area "has been considered to be a refuge for ice-dependent species in a future ice-free summer Arctic," said study co-author Kristin Laidre, a principal researcher at the Polar Science Center and an assistant professor in the University of Washington's (UW) School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences.

"If, as the paper shows, the area is changing faster than expected, it may not be the refuge we have been depending on," Laidre told Live Science in an email.

The Last Ice Area spans more than 1,200 miles (2,000 kilometers), reaching from Greenland's northern coast to the western part of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. There, sea ice is typically at least 5 years old, measuring about 13 feet (4 meters) thick.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In recent decades, ocean currents have bolstered ice cover in the Last Ice Area with chunks of floating sea ice. But researchers discovered that in 2020, northward winds transported ice away from Greenland and created stretches of open water that were warmed by the sun. The heated water then circulated under sea ice to drive even more melting, said lead study author Axel Schweiger, chair of UW's Polar Science Center.

Polar scientists first suspected something might be amiss in the Last Ice Area in 2018, when a stretch of ice-ringed open water, known as a polynya, appeared in February, Schweiger told Live Science in an email. Then in 2020, Schweiger and his colleagues noticed another sea ice anomaly in the Wandel Sea while gathering data for an Arctic research expedition called The Multidisciplinary drifting Observatory for the Study of Arctic Climate (MOSAiC), which ran from September 2019 to October 2020.

As the scientists were developing a forecast for where the research vessel might drift, they noticed that the ship was taking "a strange-looking route" through areas that normally were covered in thick ice. "We started wondering what was happening and why, and whether it was potentially connected to what we saw in the 2018 event," Schweiger said.

On thin ice

Satellite observations and climate models revealed that in 2020, unusual northward-moving winds broke up sea ice and pushed it away from the Wandel Sea. In fact, 2020's record-low sea-ice cover would have been lower still if it hadn't been for the thick ice that drifted into the area during that year's winter months, Schweiger said.

These losses wouldn't have been possible if climate change hadn't already been chipping away at the Last Ice Area. Approximately 20% of the 2020 ice loss could be directly attributed to climate change, while 80% was linked to the wind and ocean-current anomalies, the researchers wrote.

The lowest extents of Arctic ice cover have all taken place within the past 15 years, and climate projections suggest that summer sea ice everywhere in the Arctic except the Last Ice Area could vanish completely as soon as 2040. Last year, the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) found that Arctic sea-ice minimum hit its second-lowest point of all time (after 2012), Live Science reported in Oct. 2020. And though the new study investigated only the Wandel Sea, the data hints that summer sea ice in the entire Last Ice Area may be at risk as well, the scientists said.

Ice loss is already affecting the Arctic animals that rely on it for survival, such as polar bears, ringed seals and bearded seals, "and sometimes narwhals and bowhead whales," Laidre told Live Science.

While the new study doesn't say if or when the Last Ice Area could melt completely, the trend of accelerated melt is expected to continue, Schweiger said.

"Given our results, we expect to see large patches of open water in this area more often," he said. As to how that might affect marine wildlife, that too is difficult to predict, Laidre said.

The findings were published on July 1 in the journal Communications Earth and Environment.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works. She is the author of the book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control," published by Hopkins Press.