The 1st Americans were not who we thought they were

For decades, we thought the first humans to arrive in the Americas came across the Bering Land Bridge 13,000 years ago. New evidence is changing that picture.

During the last ice age, humans ventured into two vast and completely unknown continents: North and South America. For nearly a century, researchers thought they knew how this wild journey occurred: The first people to cross the Bering Land Bridge, a massive swath of land that connected Asia with North America when sea levels were lower, were the Clovis, who made the journey shortly before 13,000 years ago.

According to the Clovis First theory, every Indigenous person in the Americas could be traced to this single, inland migration, said Loren Davis, a professor of anthropology at Oregon State University.

But in recent decades, several discoveries have revealed that humans first reached the so-called New World thousands of years before we initially thought and probably didn't get there by an inland route.

So who were the first Americans, and how and when did they arrive?

Genetic studies suggest that the first people to arrive in the Americas descend from an ancestral group of Ancient North Siberians and East Asians that mingled around 20,000 to 23,000 years ago. They crossed the Bering Land Bridge sometime between then and 15,500 years ago, said David Meltzer, an archaeologist and professor of prehistory in the Department of Anthropology at Southern Methodist University in Dallas and author of the book "First Peoples in a New World, 2nd Edition" (Cambridge University Press, 2021).

But some archaeological sites hint that people may have reached the Americas far earlier than that.

For instance, there are fossilized human footprints in White Sands National Park in New Mexico that may date to 21,000 to 23,000 years ago. That would mean humans arrived in North America during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), which occurred between about 26,500 to 19,000 years ago, when ice sheets covered much of what is now Alaska, Canada and the northern U.S.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Other, more equivocal data suggest the first people arrived in the Western Hemisphere by 25,000 or even 31,500, years ago. If these dates can be confirmed, they would paint a much more complex picture of how and when humans reached the Americas.

Related: What's the earliest evidence of humans in the Americas?

Archaeological evidence of the first Americans

Almost all scientists agree, however, that this incredible journey was made possible by the emergence of Beringia — a now-submerged, 1,100-mile-wide (1,800 kilometers) landmass that connected what is now Alaska and the Russian Far East. During the last ice age, much of Earth's water was frozen in ice sheets, causing ocean levels to fall. Beringia surfaced once waters in the North Pacific dropped roughly 164 feet (50 meters) below today's levels; it was passable by foot between 30,000 and 12,000 years ago, Meltzer and Eske Willerslev, a geneticist at the University of Cambridge, wrote in a 2021 review in the journal Nature.

From there, the archaeological picture gets muddier. The older version of the story originated in the 1920s and 1930s, when Western archaeologists discovered sharp-edged, leaf-shaped stone spear points near Clovis, New Mexico. The people who made them, now dubbed the Clovis people, lived in North America between 13,000 and 12,700 years ago, based on a 2020 analysis of bone, charcoal and plant remains found at Clovis sites.

At the time, it was thought that the Clovis traveled across Beringia and then moved through an ice-free corridor, or "a gap between the continental ice sheets," in what is now part of Alaska and Canada, Davis, who leads excavations at an ancient North American site in Cooper's Ferry, Idaho, told Live Science.

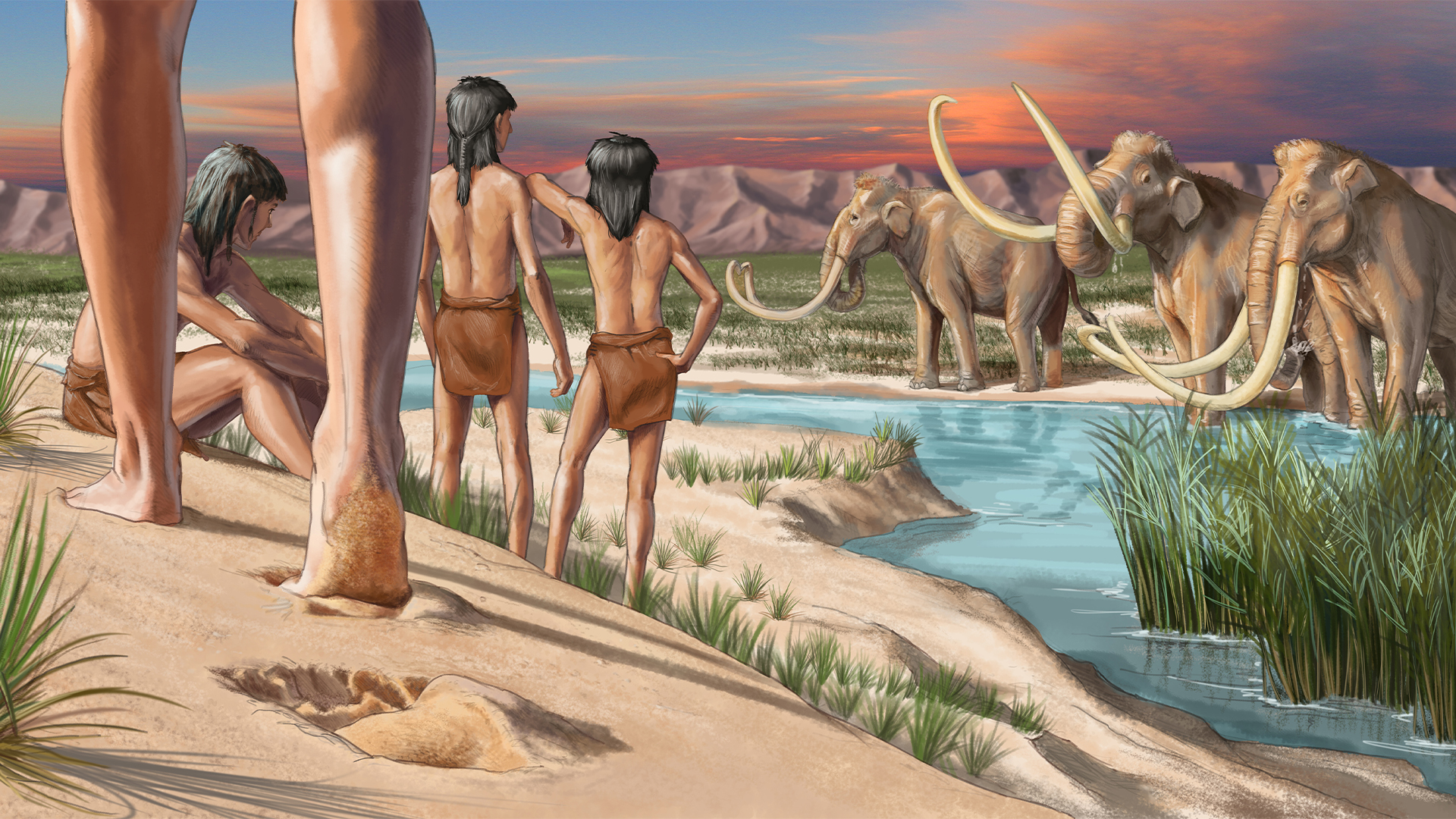

"Once they exited, they spread quickly throughout the Americas, bearing a signature stone tool known as the Clovis spear point," which was likely used to hunt megafauna, such as mammoths and bison, as well as smaller game. For decades, it was challenging to suggest the first Americans arrived any earlier than 13,000 years ago.

Slowly, however, new discoveries began turning back the clock on the first Americans' arrival. In 1976, researchers learned about the site of Monte Verde II in southern Chile, which radiocarbon dating showed was about 14,550 years old. It took decades for archaeologists to accept the dating of Monte Verde, but soon, other sites also pushed back the date of humans' arrival in the Americas.

The Paisley Caves in Oregon contain human coprolites, or fossilized poop, dating to about 14,500 years ago. Page-Ladson, a pre-Clovis site in Florida with stone tools and mastodon bones, dates to about 14,550 years ago. And Cooper's Ferry — a site that includes stone tools, animal bones and charcoal — dates to around 16,000 years ago. Then, in 2021, scientists announced much more ancient traces of human occupation: fossilized footprints in White Sands, New Mexico dating to between 21,000 and 23,000 years ago.

Related: 13 of the oldest archaeological sites in the Americas

There are dozens more sites, although some of the older ones are controversial. For instance, some archaeologists said 31,500-year-old rocks in a remote Mexican cave were stone tools made by humans, but a rebuttal argued that the rocks got their shapes naturally. Another site, in Brazil, holds giant sloth bones that may have been modified by humans at least 25,000 years ago, but a narrow hole in the bones could have occurred naturally, Davis told Live Science. And 50,000-year-old stone tools at Pedra Furada in Brazil may have actually been made by capuchin monkeys, a 2022 study in the journal The Holocene found.

Sites such as White Sands and Cooper's Ferry have big implications for how the first people arrived in the Americas. It's thought that the ice-free corridor through North America didn't fully open until about 13,800 years ago. So if humans were in the Americas long before then, they likely traveled there along the Pacific coast.

That coastal journey could have been made by foot, by watercraft, or both. But no fossil or archaeological evidence of this journey has been unearthed.

"We've never found a boat; we've never found a submerged site out on a 16,000-year-old shoreline in British Columbia," Davis said.

Still, the coastal route isn't outlandish. "There's a lot of evidence that suggests that people had the capability to do large ocean crossings," Davis said. For instance, people used boats to reach Australia by around 50,000 years ago.

Despite these uncertainties, researchers have ruled out some of the wildest theories. For instance, the first Americans weren't Pacific Islanders who boated across the open ocean, because people didn't migrate to Polynesia until around 3,000 years ago and genetic evidence shows that the first Americans are only very distantly related to Polynesians.

Likewise, genetic studies rule out the "Solutrean hypothesis," which posits that Paleolithic Europeans came across the Atlantic around 20,000 years ago, according to the 2021 Nature review.

Genetic evidence

Geneticists studying the first Americans tend to paint a more consistent picture than archaeologists do, mainly because they're using the same human remains and genetic datasets. Genetic analyses have found that Ancient North Siberians and a group of East Asians paired up around 20,000 to 23,000 years ago, Jennifer Raff, an associate professor of anthropology at the University of Kansas and author of the book "Origin: A Genetic History of the Americas" (Twelve, 2022), told Live Science.

Soon after, the population split into two genetically distinct groups: one that stayed in Siberia, and another, the basal American branch, which emerged around 20,000 to 21,000 years ago. Genetic data suggest the descendants of this basal American branch crossed the Bering Land Bridge and became the first Americans.

Related: Did cats really disappear from North America for 7 million years?

The basal American branch then split into three groups: unsampled population A (UPopA), a mysterious "genetic" ghost that has "only been detected indirectly from the genomes" of the Mixe, of what is now Mexico, Raff said; Ancient Beringians, who have no known living descendants; and Ancestral Native Americans (ANA), whose descendants live on today.

All three of these groups ultimately made it to North America, but their diverging genetics suggests that they crossed in separate movements, Meltzer and Willerslev wrote in the review. Some didn't make it very far; The Ancient Beringians entered Alaska but never made it south of the continental ice sheets. The last known Ancient Beringian, known as the "Trail Creek individual," died around 9,000 years ago in Alaska.

Meanwhile, the ANA lineage underwent several splits, suggesting that these people settled in different areas of North America as they had limited gene flow between them, Raff said. There was one split between 21,000 and 16,000 years ago and then a second one around 15,700 years ago. During this second split, the Northern Native Americans — whose living descendants include speakers of the Algonquian, Salishan, Tsimshian and Na-Dené language groupings — separated from the Southern Native Americans (SNA), who spread southward and whose descendants include the Clovis, Raff said.

Every known living and deceased Indigenous "individual south of Canada belongs to SNA," Raff said.

What's next?

Ideally, archaeologists would like to find more sites from all of these branches, especially any remains that could explain the genetics behind the people at White Sands between 23,000 and 21,000 years ago. "Right now I’m really eager to find evidence that reconciles the presence of people at White Sands during the LGM ... and the genetic signature of migration that seems to have occurred later," Raff told Live Science in an email. "As well, sites from Eastern Beringia that can help us better understand the movement of peoples through that region." But that's a challenging task.

For one, when archaeologists do uncover exceptionally preserved sites, they find that "upwards of 90% of what people made and used was perishable. It's plant fibers, it's feathers, it's animal skins and the like," said Edward Jolie, an associate professor of anthropology at the University of Arizona and the associate curator of ethnology at the Arizona State Museum.

Such organic artifacts and remains typically preserve well only in rare circumstances: extremely wet, dry or cold places, such as caves, rock shelters or water-logged sites, Jolie told Live Science.

Even if there are other well-preserved organic-material-rich sites waiting to be discovered, many scientists aren't looking for them. Instead, they are stuck in a Clovis mindset, hunting for the stone tools ancient people crafted, said Matthew Bennett, a professor of environmental and geographical sciences at Bournemouth University in the U.K. and a leader with the footprint excavations at White Sands.

But evidence of these long-lost people can also be found in the remains of the animals they butchered, the charcoal they burned, the tools they crafted and the loved ones they buried. Bennett and his colleagues are focused on the fossilized footprints these ancient individuals left behind, and the field won't move forward until more archaeologists focus on such evidence, Bennet told Live Science.

"There are other types of evidence other than stone tools," he said.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.