Humans were in South America at least 25,000 years ago, giant sloth bone pendants reveal

Humans were living in Brazil earlier than previously thought, prehistoric sloth-bone pendants suggest.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The date that humans arrived in South America has been pushed back to at least 25,000 years ago, based on an unlikely source: bones from an extinct giant ground sloth that were crafted into pendants by ancient people.

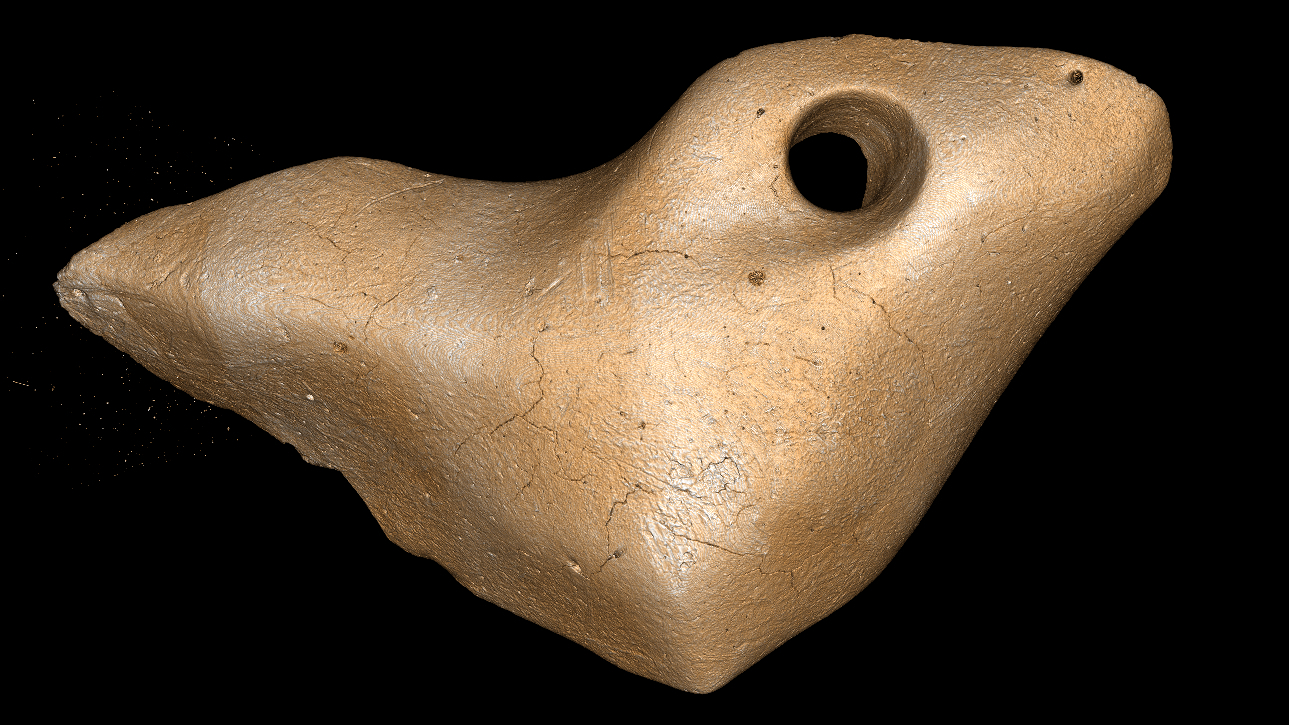

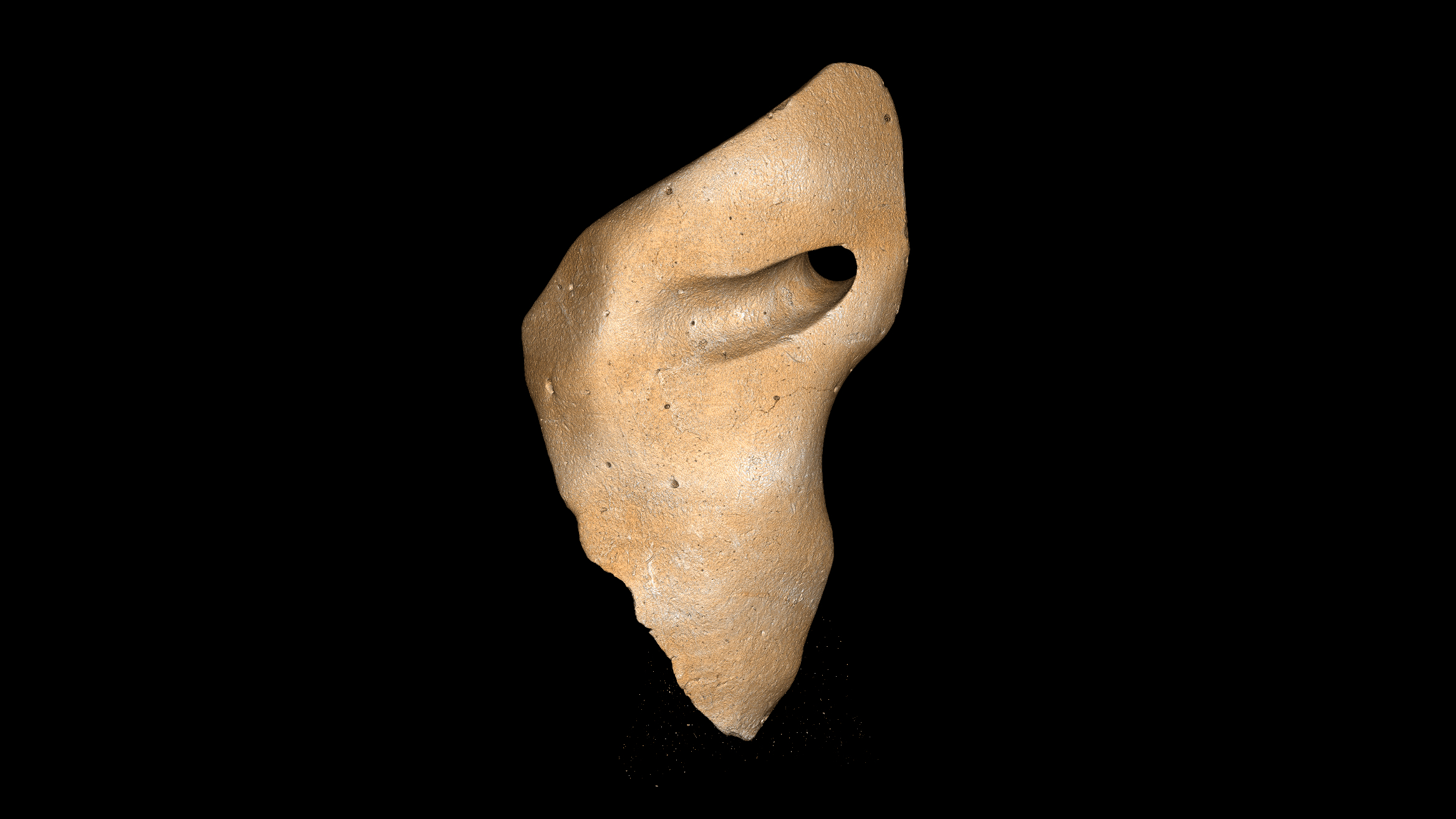

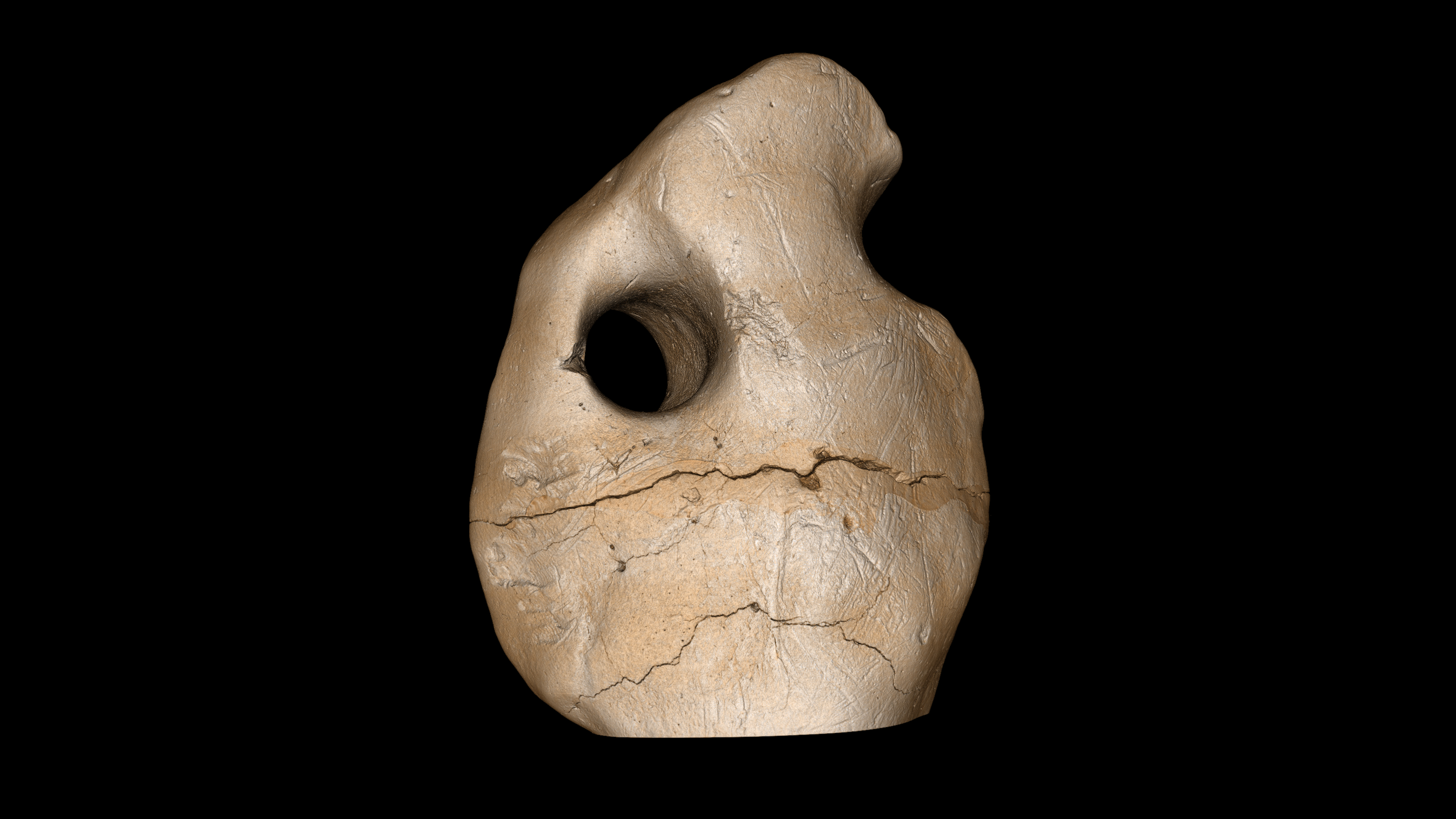

Discovered in the Santa Elina rock shelter in central Brazil, three sloth osteoderms — bony deposits that form a kind of protective armor over the skin of animals such as armadillos — found near stone tools sported tiny holes that only humans could have made.

The finding is among the earliest evidence for humans in the Americas, according to a paper published Wednesday (July 12) in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

The Santa Elina rock shelter, located in the Mato Grosso state in central Brazil, has been studied by archaeologists since 1985. Previous research at the site noted the presence of more than 1,000 individual figures and signs drawn on the walls, hundreds of stone tool artifacts, and thousands of sloth osteoderms, with three of the osteoderms showing evidence of human-created drill holes.

The newly published study documents these sloth osteoderms in exquisite detail to show that it is extremely unlikely that the holes in the bones were made naturally, with the implication that these bones push back the date humans settled in Brazil to 25,000 to 27,000 years ago. These dates are significant because of the growing — but still controversial — evidence for very early human occupation in South America, such as a date of 22,000 years ago for the Toca da Tira Peia rock shelter in eastern Brazil.

Using a combination of microscopic and macroscopic visualization techniques, the team discovered that the osteoderms, and even their tiny holes, had been polished, and noted traces of stone tool incisions and scraping marks on the artifacts. Animal-made bite marks on all three osteoderms led them to exclude rodents as the creators of the holes.

"These observations show that these three osteoderms were modified by humans into artefacts, probably personal ornaments," the researchers wrote in their paper.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In an email to Live Science, study co-author Mírian Pacheco, a lecturer in paleontology at the Federal University of São Carlos, Brazil, noted that "it is virtually impossible to define the real meaning these artifacts had for the occupants of Santa Elina." However, the shape and large number of osteoderms "may have influenced the making of a specific type of artifact such as a pendant," she said.

The presence of human-modified sloth bones in association with stone tools from geological layers that date to 25,000 to 27,000 years ago is strong evidence that people arrived in South America far earlier than previously assumed.

"Our evidence reinforces the interpretation that our colleagues working on Santa Elina have been talking about for 30 years," Thaís Pansani, a paleontologist at the Federal University of São Carlos in Brazil, said in an email to Live Science — namely, that "humans were in Central Brazil at least 27,000 years ago."

The finding shows that ancient people used sloth remains in a variety of ways, said Matthew Bennett, a geologist at Bournemouth University in the U.K. who has researched human-sloth interactions in North America but was not involved in this project.

"This is an exciting piece of work which may, in time, support the idea of peopling of the Americas during the Last Glacial Maximum," the coldest part of the last ice age, Bennett told Live Science in an email.

However, many sites in South America have not yet been fully studied, meaning the debate about humans' arrival in the Americas is far from over. "We believe that there should be more evidence waiting to be found in the rock shelters and caves of Brazil in places little or not explored," Pansani said.

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Kristina holds a Ph.D. in biological anthropology and an M.A. in classical archaeology from the University of North Carolina, as well as a B.A. in Latin from the University of Virginia, and she was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus