Incredible Fossilized Footprints Suggest That Early Humans Stalked Giant Sloths

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

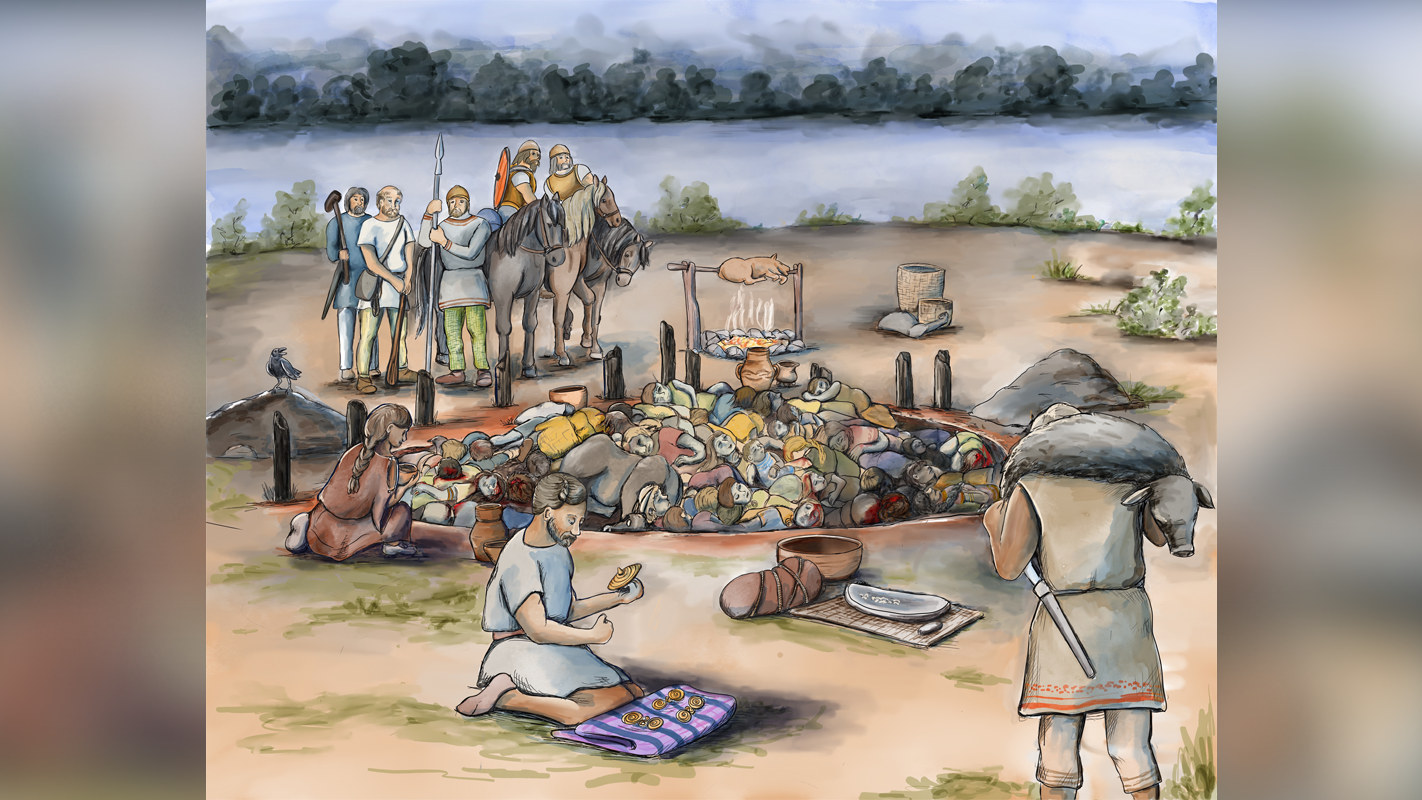

A bigfoot-like ground sloth had unwelcome company about 11,000 years ago. No matter which way the giant creature went, ancient humans followed it, stepping in its elongated, kidney-shaped paw prints as they tracked the furry beast, a new study suggests.

Finally, it seems that the giant ground sloth couldn't take it anymore. It reared up on its hind legs — likely standing as tall as 7 feet (2.1 meters) — and swung its sharp, sickle-shaped claws around, looking at the unwanted human interlopers, according to an analysis of the fossilized foot, paw and claw marks left at the site.

What happened next remains a mystery. It's possible the humans attempted to kill the sloth and may have succeeded, said study co-researcher Matthew Bennett, a professor of environmental and geographical sciences at Bournemouth University in the United Kingdom. [Photos: These Animals Used to Be Giants]

But, given that the vast majority of hunts led by modern-day hunter-gatherers aren't successful, and that "sloths are so densely muscled," it would have been hard to overpower the animal with a stone weapon, so an outright kill is unlikely, the researchers wrote in the study.

Remarkable footprints

Researchers found the prints left by this giant ground sloth and humans in New Mexico's White Sands National Monument park in April 2017. The find was a breakthrough for study lead researcher David Bustos, of the National Park Service, who had long suspected that fossilized footprints of ancient humans were hidden on the grounds of the monument.

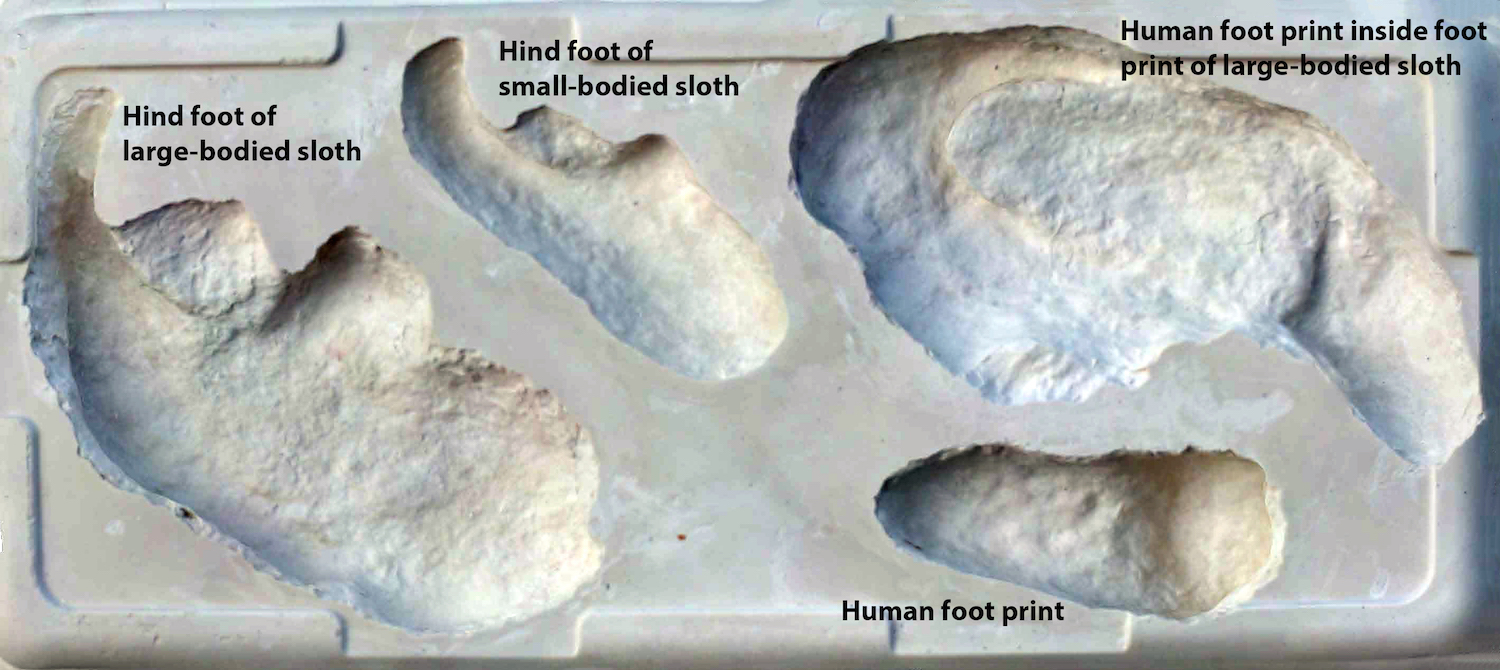

Even more surprising was the fact that some of the human footprints were found inside the sloth tracks, indicating that ancient people had followed the prints while they were still fresh in the sandy mud. Track marks from other giant, now-extinct animals, including mammoths, wolves, big cats, camels and cattle have also been found on the fossil-rich site.

However, there were fewer than a dozen sloth track marks with human footprints inside, Bennett said. These sloth tracks were likely left by either Nothrotheriops or Paramylodon and were likely made by several animals of different ages, the researchers said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Calling Sherlock Holmes

The prints reveal that ancient humans and giant ground sloths did, in fact, interact at the end of the last ice age. This evidence is key to figuring out whether humans stalked and hunted the furry giants, which went extinct around this time, as did other large mammals, including the mammoth and North American horse.

There's an ongoing debate about whether human hunters or climate change ultimately led to the extinction of these large creatures, Bennett said. According to a 2016 study in the journal Science, a perfect storm of humans and a warming climate doomed the ice age giants.

Beyond this, it's challenging to play Sherlock Holmes on a trackway that was made 11,000 years ago. But researchers have some ideas. One is that human hunters were following and harassing the giant ground sloths, distracting them so they could be more easily hunted, the researchers said.

Another idea is that humans' actions were playful and curious rather than ominous. "But human interactions with sloths are probably better interpreted in the context of stalking and/or hunting," the researchers wrote in the study. "Sloths would have been formidable prey. Their strong arms and sharp claws gave them a lethal reach and clear advantage in close-quarter encounters." [Sloth Quiz: Test Your Knowledge]

The study is a "solid" one — "they have done a very thorough job of documenting and analyzing the trackways," said William Harcourt-Smith, a paleoanthropologist at Lehman College and the American Museum of Natural History, both based in New York City, who was not involved with the research.

But it's good to be cautious when imagining the ancient scene, Harcourt-Smith said. It's possible that the sloths made the tracks and humans followed an hour or so later — meaning that the humans weren't hot on the sloths' tail.

"How many times have children, or even adults, followed in the footsteps of others in the snow or sand, simply for the fun of it?" Harcourt-Smith told Live Science.

However, it's definitely possible that the "flailing" marks that the sloth made in the ground with its enormous claws were prompted by the presence of humans, Harcourt-Smith said. But without any surviving weapons or butchered animal bones, it's anyone's guess what happened next, he said.

The study was published online today (April 25) in the journal Science Advances.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus