See the likeness of Bonnie Prince Charlie, who led Scottish clan uprising against the British crown

The new look of Charles Edward Stuart as a young man is based on forensic studies of his death masks.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Scientists have reconstructed the face of "Bonnie Prince Charlie" — the disinherited pretender to the thrones of England, Scotland and Ireland who in 1745 led an ill-fated rebellion of Scots and other supporters against the united British crown.

Stories of the prince, whose real name was Charles Edward Stuart, have become legendary, especially in Scotland, and he's a major character in the time-traveling TV series "Outlander."

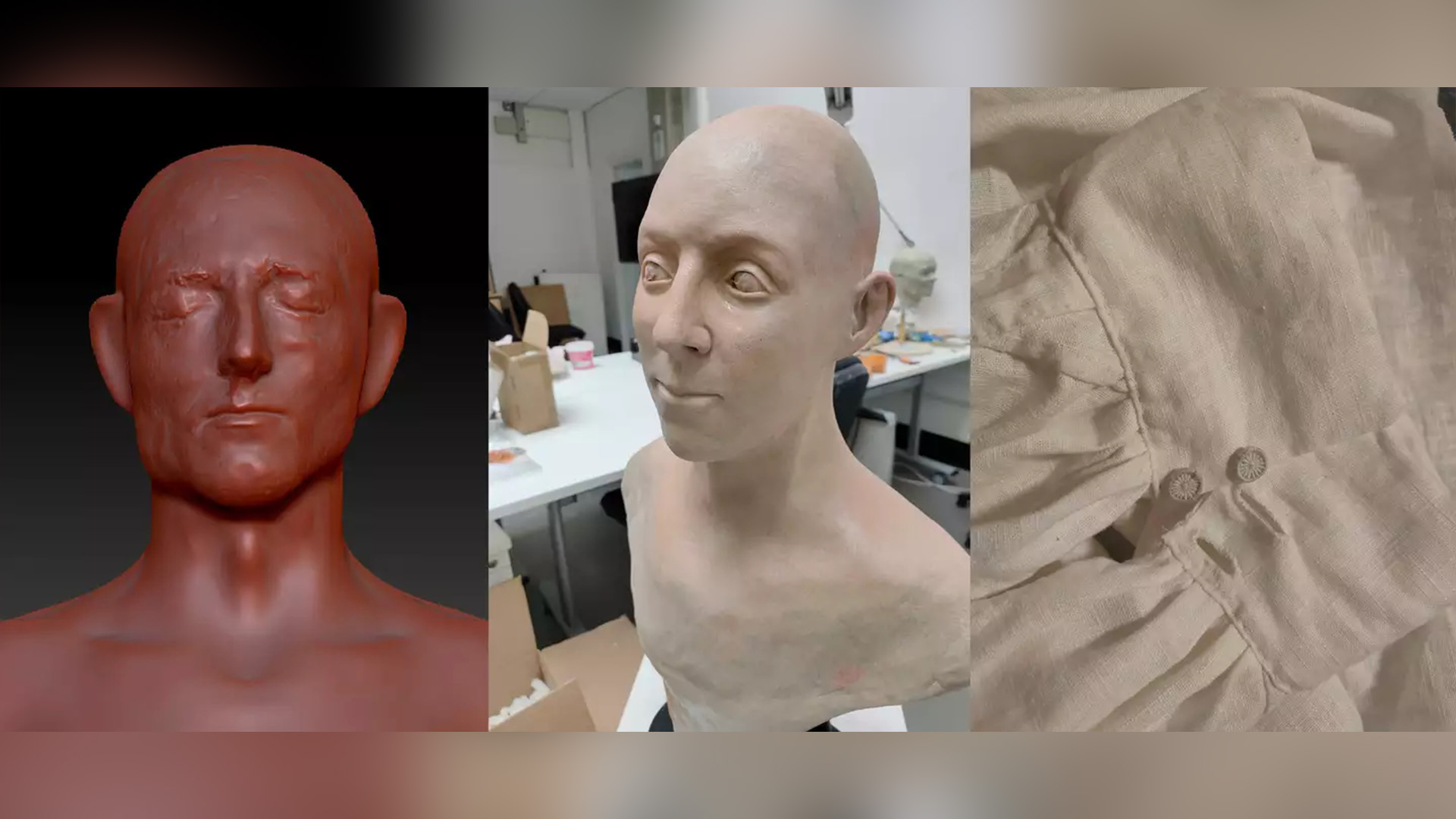

Now, a three-dimensional model of how the prince looked during the rebellion has been unveiled at the University of Dundee in Scotland. It's based on the work of Barbora Veselá, a master's student at the university's Centre for Anatomy and Human Identification, who analyzed the prince's facial structure from his death masks.

The latest depiction may be slightly at odds with depictions of the "bonnie" prince — a Scottish appellation meaning "handsome" — who looked dashing and regal in contemporary portraits.

Those portrayals may have been intentionally flattering; in contrast, the intent of the reconstruction was to show Bonnie Prince Charlie "as a person, stripping off the layers of royalty and leaving him plain, showing him as a human being," Veselá told Live Science.

However, it's curious that the new reconstruction doesn't look much like those portraits, which tended to resemble one another, historians told Live Science.

Related: 35 amazing facial reconstructions, from Stone Age shamans to King Tut

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Jacobite uprising

Charles Edward Stuart was the grandson of England's James II (Scotland's James VII), who had been deposed by English politicians in the "Glorious Revolution" of 1688 because he was a Catholic who believed he ruled by divine right.

James was replaced with his Protestant son-in-law and daughter, the "co-regents" William III and Mary II, on the condition that they allowed the English Parliament to control laws and taxation. Scotland soon made a similar deal.

James died in France in 1701, leaving his son James Francis Edward Stuart — known as the "Old Pretender" — to continue the family line. The Old Pretender's son Charles Edward Stuart — the "Young Pretender" — landed in Scotland in July 1745 to reclaim the thrones of England, Scotland and Ireland from the successors of William and Mary.

The 1745 rebellion — known as the Jacobite uprising, from the Latinized name of the deposed king — was initially successful, and Bonnie Prince Charlie led his army south into England. But he retreated from advancing English armies in January 1745, and on April 16, 1746, the Jacobites were defeated at the Battle of Culloden near Inverness.

Bonnie Prince Charlie escaped and began a fugitive journey around Scotland's northwest; at one point he disguised himself as a serving maid to avoid capture. His flight inspired the "The Skye Boat Song," a version of which features in "Outlander." The prince then returned to France, and then Italy, and died in Rome in 1788 at age 67.

Bonnie prince

The new depiction of Bonnie Prince Charlie is based on precise measurements of two masks produced from a cast of his face made soon after he died — a common practice at the time. The researchers used forensic techniques to determine how he looked when he died and applied "anti-aging" software to estimate his appearance during the uprising, more than 40 years before his death.

Veselá said portraits of Bonnie Prince Charlie show him dressed in expensive clothes and formally posed. But "they only show one facet of who he was," she said, adding that he was also someone who enjoyed "horse riding, boating, music, being outdoors, and interacting with his followers and men who were not aristocrats."

Some historians who weren't involved in the reconstruction are cautious about the new portrayal.

Murray Pittock, a professor at the University of Glasgow who has extensively studied Jacobite history and written several books about it, said the forensic techniques the researchers used would provide vital information to investigators of a crime. In the case of Bonnie Prince Charlie, however, several portraits show what he possibly looked like — "and they all look more like each other than they look like the reconstruction," he told Live Science.

Historian Arran Johnston, who recently completed the book "The Battles of Bonnie Prince Charlie" (2023, Pen and Sword), said the reconstruction showed how difficult it is to "capture the essence of a living person."

"What really mattered about Charles Edward Stuart is his spirit, his natural capacity to draw people to him and make them willing to risk it all," he told Live Science.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus