Maya ruler burned bodies of old dynasty during regime change, charred human remains reveal

Charred human remains and ornaments found at a Maya temple were part of a ritual.

A large, charred deposit containing royal human remains and ornaments found inside a Maya temple-pyramid was likely part of a "dramatic and public ritual" during a regime change.

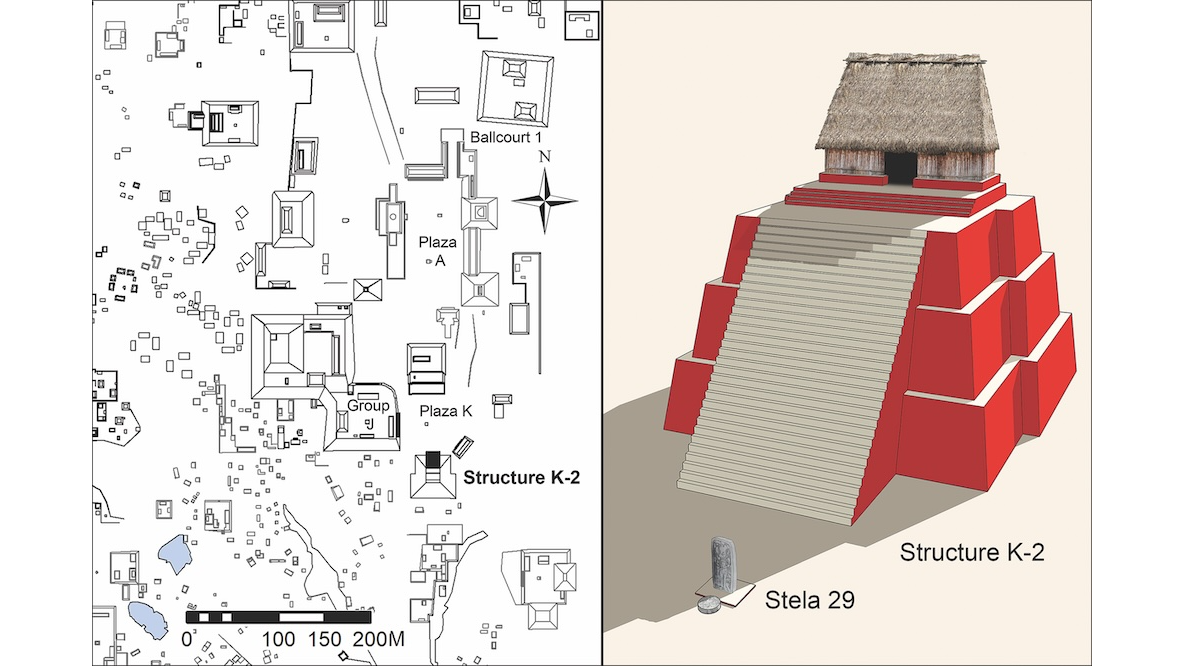

Archaeologists discovered the aftermath of the destructive event in K'anwitznal (also called Ucanal), an archaeological site in northern Guatemala, according to a study published Thursday (April 18) in the journal Antiquity.

After hauling away soil in bags and carefully sifting through their contents, researchers uncovered bits of scorched human bones, as well as hundreds of pieces of personal adornments made from valuable materials, according to a statement.

"There was a large concentration of soot, carbon and ashes mixed with burnt bones and fragments of jadeite and marine shells that were so severely burned that they had cracked and exploded," lead study author Christina Halperin, a professor of anthropology at the University of Montreal, told Live Science. "At first we didn't know what we were looking at."

But then researchers discovered the remnants of a greenstone mask made of jade and two obsidian pieces that would have served as pupils for the mask, similar to other Maya masks worn by royalty.

"It didn't hit home that we were looking at ornaments until we found the diadem [crown]," Halperin said. "Only royal individuals would have worn something like that. We knew it had to be a royal tomb."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers radiocarbon-dated bones and charcoal found at the site and discovered that the dates didn't match up. While the charcoal was from sometime between A.D. 773 and 881, the bones were dated to decades earlier, "suggesting that the tomb was reentered specifically to burn the royal remains, which were then deposited in the construction of a new phase of a temple-pyramid," according to the statement.

"The bones were very fragmented, but we were able to determine that the remains were from at least four individuals," Halperin said. "It's difficult to identify them but we do know that one was definitely an adult male."

At least two of the individuals were royals, according to the study.

Archaeologists determined that the burning event coincided with a regime change in which community members "rejected a Late Classic (A.D. 600 to 810) Maya dynasty and instantiated a new era of political order" with the introduction of a new ruler known as Papmalil, "who may have been a foreigner," according to the statement.

"In written texts, there's evidence of a political crisis taking place during this time period," Halperin said. "This [burning] event occurred as part of the beginning of a new era of political rule."

The ritual reentering of tombs was a common practice for the Maya, whose hieroglyphic texts revealed similar acts of desecration over the years, the team said.

"The ancient Maya were always reworking their society for better or for worse, and were often in a state of transition," Halperin said.

Jennifer Nalewicki is former Live Science staff writer and Salt Lake City-based journalist whose work has been featured in The New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, Popular Mechanics and more. She covers several science topics from planet Earth to paleontology and archaeology to health and culture. Prior to freelancing, Jennifer held an Editor role at Time Inc. Jennifer has a bachelor's degree in Journalism from The University of Texas at Austin.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus